“Failure is not an Option”: Cambodian-Born Secret Service Agent Hopes to Make History in Cambodia

- By Teng Yalirozy

- February 20, 2024 12:05 AM

PHNOM PENH – “I made history in the U.S., so I want to make history in Cambodia as well,” said Oun Bun Leth who left Cambodia as a refugee seeking a new life in the U.S. in 1983, four years after the fall of the genocidal regime of Pol Pot.

Born in a military family whose father served in the army during the United States-backed Lon Nol regime, from 1970 to 1975, Bun Leth worked as a Secret Service Officer, protecting four different presidents: George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

Bun Leth met with Cambodianess during a visit he paid to his country of birth in mid-February, about four months after his retirement. He talked about his life in America as a kid who spoke no English, his journey to the position and his plans for the future.

Teng Yalirozy: You served four different U.S. presidents and left Cambodia for 40 years. When you first touched the Cambodian soil, what came to your mind and did you miss the most about your childhood?

Oun Bun Leth: Thank you for having me here. I came back to Cambodia for the first time in 2012, with President Obama. When the airplane touched down, I was kind of scared because most of my family was military [soldiers were targeted by the Khmer Rouge for having served a U.S.-backed regime]. So I didn’t want to get out of the car because I was thinking I would be shot. But taking a few minutes and a deep breath, the humidity and the smells made it Cambodia, and everything was okay.

My parents worked so hard and made me who I am today. Without them, I wouldn’t be here today. After my father was killed [by the Khmer Rouge], my mother had to take a double duty. Being a mom and a dad. She sacrificed a lot. The love of a mother is huge and unmeasurable. Of course, communists killed most of them. I was nine when everything happened. I was separated from my family – no food, no shelter and no house. ‘From No House to White House’ is one of the chapters in the book [A Refugee’s American Dream] that people love.

In 1979, when the Vietnamese liberated [Cambodia from Pol Pot’s regime] and the situation was even more chaotic, my mother did everything she could to make sure we survived. Things were getting worse, so my mother and I decided to go to Thailand to do some business across the border. We went there on foot, which was like a 75-mile walk, and made dozens of these cross-border trips.

We made very little just to survive. Our last trip was in late 1979. Then, there were gunfights between the Vietnamese, Khmer Rouge, the Thai and the freedom fighters. The next morning, the Refugee Relief came, and we were told that we couldn’t stay there anymore. They picked us up and tossed us in a pickup truck to go to the first refugee camp which was Khao-I-Dang. We stayed there for months. The camp was filled with other refugees. They moved us to Sa Kaeo Refugee Camp and then to Kamput Camp where the United States, under President Ronald Reagan, accepted more political refugees. So, my mom asked people around and submitted several applications to be granted refugee status. America never came into our mind; we were thinking about France because it had been [in the region] for a long time, or Australia and Canada. We never thought of America.

Teng Yalirozy: How did you end up in the U.S. if you had no idea about it?

Oun Bun Leth: In the Kamput Camp, they asked about my dad. He was a soldier and served in the army in the Second World War. Most of my family members were soldiers. Historically Lon Nol was backed by Americans. So, they considered my dad was working for America.

In the process, my name was misspelled from Seuth to Leuth, so that is how I got my current name. But I have accepted it ever since.

We then were moved from Thailand to the Philippines, to what they called a processing center, to deal with our paperwork. We stayed there for six months and were taught basic conversation in English and social skills in the West, like how to use the bathroom.

At that time, we were still unsure of what our last destination would be. We still had France as the first choice. But in the end, we learned it was going to be America. We arrived there in October 1983.

Teng Yalirozy: What was it like, arriving in a new country that you had no idea about?

Oun Bun Leth: We were shocked – the language, the people, the weather. It was like you were reborn into a new country. My mom, my nephew and I came first. My older sister came 3 or 4 months later. My mom and I had so much bond, we were pretty close. She passed away in 2018 at almost 101 years old. As a single woman who went through a lot, she still lived to be over 100 years old. I’m always joking that if I live until 95, I’ll be good.

We had to learn the language, which was very difficult, and the culture was totally different. So, I put a lot of time into high school. I was already 18 when I arrived there. Most people had already graduated from high school at this age.

Teng Yalirozy: Despite being already 18, you were allowed to go to high school? If you didn’t speak English, how could you follow what was taught in the class?

Oun Bun Leth: Yes, and I graduated high school at 21. It took me three years. They have a system that is called English as a second language. We went there in ninth grade, and they taught us things from the very basics, starting with the alphabet. We were put at the back of the classroom. Those who spoke the language sat in front of the class and learned different things. The class was in English, but they divided us into two different groups of people: Those who had English notions and those who did not.

Teng Yalirozy: Was it hard for you to be put at the back of the class?

Oun Bun Leth: Hard, I wouldn’t say that. It was so unhop-for to have made it to the U.S. I thought I would never be able to speak English. Cambodian and English are totally different. One day, I told my mom that it was going to be likely that we would never be able to go anywhere if we lived in America and did not speak English. So I did what it took to learn it. I learned and practiced for lots of hours, days in and days out. I had to be open-minded when people taught me certain things and how to talk. Besides learning English, I was working.

Teng Yalirozy: You worked while doing high school?

Oun Bun Leth: Over there, you are allowed to work part-time at 16 years old, which means 15 hours a week until you’re 18. I was washing dishes in a Chinese restaurant and paid $3.15 per hour. It was a good thing, but it was a minimum wage.

Teng Yalirozy: Did you go to college?

Oun Bun Leth: I did. I studied Sociology and Criminal Justice. I have a high school degree and two college degrees.

Teng Yalirozy: How did you end up being a Secret Service officer at the White House? Had you dreamed that you would be there and protecting U.S. presidents?

Oun Bun Leth: Fortune tellers are very common in Cambodia. But if one of them had told me that, I would have never believed it! But, I never stopped trying harder and I slowly realized I wanted to work for the State and the Federal Government.

So, the Secret Service came to my mind after the 9/11 incident. I walked up there and applied for a job. I told myself I would make it clear. I wasn’t born here and was a refugee from Cambodia. I had been naturalized. I thought Secret Service officers and Agents were only for white people, but here I am, attempting to. I had to take three written tests to pass and got through a physical test, where I had to see the doctor. It took me almost six months to get there. Then, they investigated my background for any criminal records or past drug usage. If you have anyone of those, you are not qualified. The final stage was physical training, learning self-defense and shooting from a pistol, short gun and machine gun. You have to pass everything. If you fail one, you’re out.

Teng Yalirozy: How difficult was it to get into the Secret Service role?

Oun Bun Leth: Out of 1,000 people, only 10 or 20 are accepted. I was the first Cambodian ever to join the Secret Service since it was established in 1865.

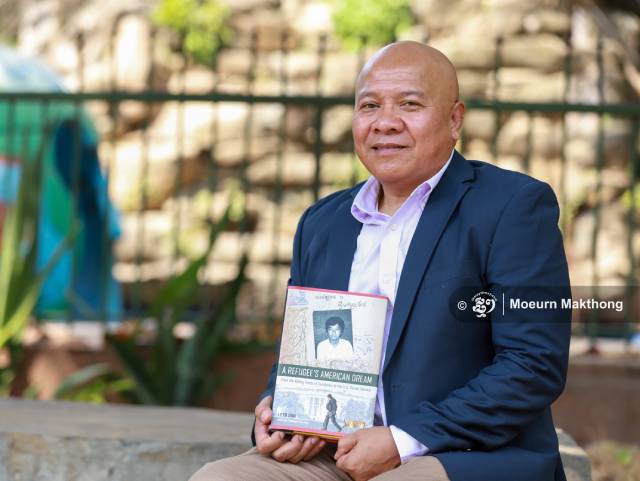

It was shocking that I was accepted. I looked back to the kid I was: Born into a poor family, went through a civil war and eventually ended up in a country that I knew nothing about. Even though I was a hard worker, I never dreamed of walking into the White House. I have written a book about my life story called “A Refugee’s American Dream: From the Killing Field in Cambodia to the Secret Service.”

Teng Yalirozy: What was it like walking into the White House for the first time?

Oun Bun Leth: I pinched and asked myself if it was real or just a dream. I could walk everywhere except from the president’s bedroom. It’s forbidden.

Teng Yalirozy: As a Secret Service officer, what did you do?

Oun Bun Leth: I did protection in the first five years. Then, I was selected to join the K-9 team [the team that trains police dogs to assist with certain duties]. My role was to go to certain places before the presidents to make sure that it was safe and secure. My K-9 team worked as bomb detectors, which means we were specifically looking for bombs, often with the support of dogs. My dog is actually bilingual: He speaks Khmer and English. We were the advanced team and made sure the president got to the place with no hidden bombs. We were always on standby, under the utmost pressure.

In the Secret Service, failure is not an option. There are no mistakes. You have to be 100 percent right. You are protecting the most powerful people.

If you’re not sure, someone’s going to die and you’ll have to pay for it. If something had happened under my term, I would have had to go in front of Congress and tell them what happened. It’s a lot of responsibility.

Teng Yalirozy: Was the position hard to handle? What would happen to you if you made a mistake?

Oun Bun Leth: It was stressful. Everything you do is your responsibility. If something happens, it’s your responsibility. It’s not heavy lifting but stressful. That’s why I don’t have hair anymore. We referred to the people we protected as a ‘protectee’. Protectees could be the President, Vice President or their families. Joining the Secret Service is like you are sacrificing your life for their safety. If you make any mistake, you’re going to be fired or suspended for months without pay. That’s why mistakes rarely happen.

Teng Yalirozy: How do you interact with the presidents? Do they know you’re from Cambodia?

Oun Bun Leth: I talked to them all the time. We shook hands. They didn’t know I was from Cambodia because it would be too political. If you get into that, they would be going to call you more, and people would not be going to like that. If you get too close to one president, the next president is going to ask you to leave.

Teng Yalirozy: After being retired, do you feel some kind of fulfillment with how far you’ve come, arriving in the U.S. as a refugee and working at the White House?

Oun Bun Leth: I just look at it from the perspective of the kid who was growing up poor–no English, no penny–came to the U.S. and worked for the minimum wage and then protected the most powerful people in the world, traveled everywhere with the presidents. Everything I did gave me a lot of experience.

Teng Yalirozy: You’re in Cambodia 40 years later. What differences have you seen in your motherland? Do you plan to settle back in Cambodia for good and share the dog training or the Secret Service officer knowledge?

Oun Bun Leth: It’s improved a lot. Everything is growing. I can see the high-rise buildings. I came here on a vacation and hopefully, could pass on the knowledge of dog training. I’m not an expert but want to help them make dog training better and protection more efficient where other countries give more respect to Cambodia. I want to make it better. If I get a job, I will stay here. If not, I can be a consultant in the country for half a year. I made history in the U.S., so I want to make history in Cambodia as well.