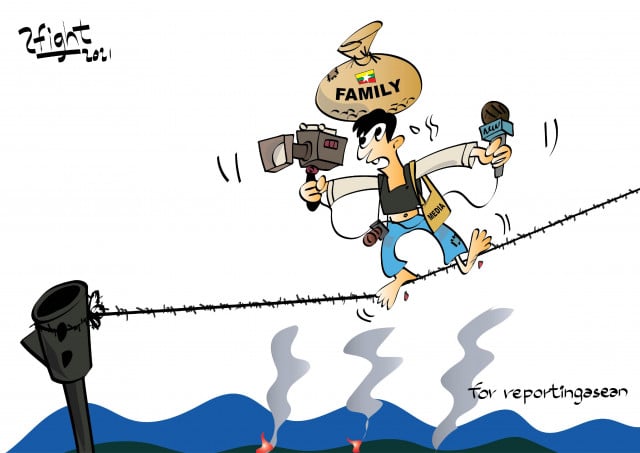

‘Get Arrested Inside or Go Hungry Abroad’: Safety, Decent Income Weigh Heavily on Myanmar’s Journalists

- By Johanna Son / Reporting ASEAN

- March 16, 2022 12:49 PM

BANGKOK | Safety and making a living wage from news work are the biggest challenges that Myanmar journalists face these days, according to insights from an exploratory survey of news professionals affected by the February 2021 coup in their country.

Fleeing or moving to a location where journalists are safer physically does not mean that they are finding stable incomes or a degree of security in work, going by comments by some respondents in the online survey, which the Reporting ASEAN series carried out in February and March 2022.

Asked to select three from a list of seven challenges to identify the biggest challenges for journalists at present, they chose physical safety first (76%), followed by 56% for ‘getting a living wage from media work’ and 55%, digital safety.

One-fourth of respondents to the survey’s online questionnaire, who range from reporters to editors, said journalists are worried by ‘finding work/having any work at all’.

The survey responses also point to the uncertainty that surrounds journalism as a profession in Myanmar: A significant proportion, or a combined total of 40%, of those in news work today say they do not know what they will be doing in a year's time or say they see themselves leaving it.

“It’s a question of whether (you) ‘get arrested inside’ or ‘go hungry abroad’,” said one journalist, who is now based in a neighbouring country. “Media houses that have moved abroad are having budget difficulties, and they can hardly support reporters in exile,” he explained.

Many exiled Myanmar journalists are in “dire need” of financial support and looking for ways to continue news work and make it their livelihood, he said. Many are connected to smaller media houses, not the ones more known outside Myanmar. He suggested that efforts to support the independent media are better invested in ways to get them to set up new, independent agencies that they can look after, and go beyond emergency financial aid to individuals.

“Journalists do not have any guarantee for safety,” said another journalist inside Myanmar. “There are mountains of challenges in reporting on the ground, such as communication, transportation and food. We are living a life similar to our revolutionary fighters.”

Assuming they are able to do reporting, the atmosphere of insecurity and mistrust in the country has made it difficult to do basic news tasks, like carrying out legwork or interviewing people. “We have to try hard to convince a potential source to talk to us,” one respondent commented.

“Lack of safety for journalists has affected not only the quality of reporting but their psyches,” one said. “People’s right to know is also seriously under threat.”

The sample size of the survey, entitled ‘Media in Myanmar: Insights from Within’, is small at 55. But there is value in seeking responses and insights from verified journalists given the security and communication challenges relating to Myanmar, a country where being a journalist has become a risk to one’s life and safety.

IN A YEAR’S TIME

Fifty of the 55 journalists in the survey were still working as such, while the rest said they had left due to the coup and its impact. Of those still in journalism, 45% said they expect to still be working as paid journalists in a year’s time – but a sizeable 29% said they did not know what they would be doing by then, and 11% said they expect to be ‘out of journalism’.

Among the five respondents who have left the profession, 86% cited reasons for this that were either financial, related to safety, or both.

Asked to look ahead to a time when Myanmar is not under the military rule and identify which aspects of journalism to rebuild, the challenge that the respondents ranked first among six options was the ‘dismantling of laws inimical to press freedom, whether post-coup ones or those in place before (eg Section 66d of the Telecommunications Act, Section 505a in the post-coup penal code)’.

“Both my job and life are broken now,” said a journalist who has been in media for nearly a decade. “In the future, this industry needs laws and bylaws to guarantee/safeguard its role in society.”

The second challenge to address was ‘professionalism’, followed by ‘independence’. Interestingly, ‘safety’ – the focus of much training and funding support in the past – was ranked last of six challenges.

The other challenges in the list, apart from the four discussed above, were ‘rebuilding an independent peer-based organization of journalists that looks after news professionals)’ and ‘financial viability’.

Of the total 55 respondents, made up of those who are still working in media and those who stopped due to the coup, 55% were male and 45% were female. Eight out of 10 were between 20 and 39 years old. A little over half, or 56%, were located inside Myanmar and 44%, outside.

About three-fourths have been in media for up to 10 years, and 95% were full-time staffers. A total of 71% were reporters or photojournalists across various media formats, with 22% being editors.

About half of the respondents were journalists from at least 11 ethnic communities, including the Bamar majority in the Southeast Asian country of over 55 million people. While all the respondents were from Myanmar, they included several who work for, or contribute to, foreign news agencies. All were affected by the coup, whether through relocation or transfer, loss or change of jobs, or other means.

LIFE – AND LIVELIHOOD

Much of the headline-grabbing information in the news has been around journalists’ safety. But there has not been as much focus - especially in the emergency phase after the coup - on the working conditions and professional arrangements in Myanmar’s media industry.

In the survey, the journalists were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with three statements that inquire into journalism as a means of livelihood, and basic labour-related benefits in the profession.

Nearly three-fourths (73%) agreed with the statement ‘I could survive on my salary as a journalist’ before the 2021 coup.

However, the replies were more mixed when it came to whether their news organisations provided basic employee benefits such health insurance, leaves and severance pay.

Nearly equal percentages of respondents agreed (53%) and disagreed (47%) with the statement saying they ‘have, or had, basic employment benefits, including any one or some of the following: paid leaves, gratuity or severance/termination pay’.

But the lack of health insurance, whether in their current news work or before they left journalism, appeared to be typical. Seventy-one percent of respondents disagreed with the statement ‘I have/had health insurance that my news organisation paid for’. The remaining 29%, or nearly a third, had employer-provided health insurance.

DISSECTING PRESS FREEDOM

Asked to rate the ‘quality of the news media in terms of independence, freedom and professionalism’ before the coup on a scale of 1 (extremely poor) to 5 (extremely good), nearly half (49%) chose option 3 or the average, and a combined figure of 38% chose 4 and 5, the higher levels of agreement.

Two other questions asked the journalists to indicate the level of support they perceive from first, their media peers, and second, their audiences.

Asked how much they can ‘count on peers to support’ them during a crackdown on media, 42% chose the average of 3 and 38% expressed strong agreement to full agreement (4 and 5).

Next, they were asked to gauge the support they get from their audiences from a range of 1 for ‘totally disagree’ to 5 for ‘fully agree’, by evaluating the statement ‘I know that news audiences support the space for independent professional media and understand why they should defend this space, even if they may not agree with what the news outlets report’. Nearly half or 49% chose strong to full agreement (4 and 5) with this statement, while 35% chose the average option of 3.

Would they agree with the statement ‘Facebook has been an ally of journalism work, especially after Feb 2021’? Almost half (49%) strongly agreed with this and selected 4, and 16% expressed full agreement, or 5. These make a total of 65% who either strongly or fully agreed with the said sentence.

The Reporting ASEAN team conducted the survey in February-March 2022, using questionnaires that were in Burmese and English.