Human Rights Situation “Gloomy” but Cause for Optimism Remains

- Sao Phal Niseiy

- August 31, 2020 9:04 AM

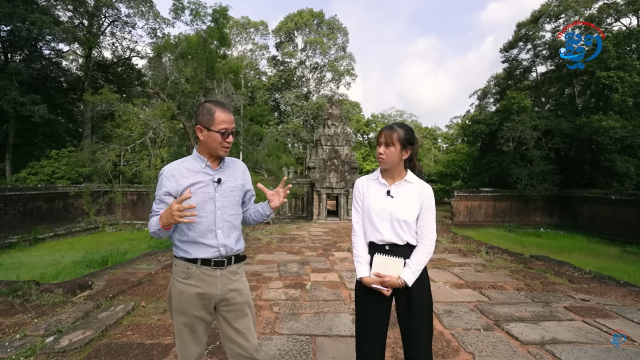

Human rights remain a contentious and problematic issue in Cambodia. In an interview with Cambodianess, Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR), shares her concerns over the alarming rights situation where fundamental freedoms are restricted. Sopheap emphasized the urgent need to prioritize rights promotion and protection. Despite all these problems, she is still hopeful and optimistic that Cambodia’s future of human rights will be bright as more Cambodians citizens increasingly are informed and expanding their participation in advocating for human rights improvement.

Sao Phal Niseiy: You have been the executive director at CCHR since 2014. Could you please share with us some of the achievements you and your organization have made so far?

Chak Sopheap: I am very proud of the work CCHR does to protect human rights in Cambodia, and our organization has made significant impact in recent years. We have become a leading organization in our field, and we have expanded our projects to be able to reach more members of the community and support more beneficiaries by working on many areas of human rights. We have programs that provide assistance to individuals on the ground, including our Protecting Fundamental Freedoms Project, through which we can provide human rights defenders and community representatives, on the ground support to continue their work.

We have programs to protect the most marginalized members of society, including our Voices for Gender Equality project and our Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, Expression and Sexual Characteristics (‘SOGIE-SC’) project, and we have incorporated an intersectional aspect to all of our programs. Furthermore, we have projects that aim to hold the government (for example the Fundamental Freedoms Monitoring Project), the court (Fair Trial Rights) and private actors (Business and Human Rights project) accountable for their human rights impacts.

These are only some examples of the work CCHR is currently doing. We are able to provide support to individuals at a grassroots level, while simultaneously raising awareness and knowledge of human rights amongst the general public, and conducting high-level advocacy. As such, I am very proud of our development as an organization and how hard people are working to protect human rights in our country.

On personal level, as one of the country's most prominent human rights advocates, my work has been recognized by the former US President Barack Obama. I am a recipient of the Indian-ASEAN Youth Award (Young Women Achiever Category) and Franco-German Prize for Human Rights the Rule of Law. I see all these rewards as a reminder to all activists in Cambodia that—despite the hurdles, the challenges and the steps backwards—we should maintain our efforts towards a more just, transparent and sustainable Cambodia.

Sao Phal Niseiy: It has been more than six years since you assumed your position and, to many, the position you hold comes with huge responsibility and is very risky—what have been your biggest challenges and how do you deal with them practically?

Chak Sopheap: Working in the restricted civic space in Cambodia presents a range of challenges, as CSOs [Civil Society Organizations] are frequently subject to intimidation and harassment for their work. One of our largest challenges as an organization was in November 2017, when CCHR faced direct threats from Prime Minister Hun Sen, who ordered the Ministry of Interior to investigate and shut down our organization due to our prior affiliation with Kem Sokha, who originally founded CCHR. CCHR responded by releasing a public statement reiterating our independence from all political parties, and our firm commitment to human rights principles.

A week later, the Prime Minister retracted his announcement and allowed CCHR to continue its operation, stating that the investigation found no wrongdoing. Notably, no visible investigation took place. Within this context, members of CCHR staff experienced intimidation and surveillance by the authorities on several occasions. One staff member was asked by an individual with ties to the ruling party for information about CCHR staff movements. CCHR was the target of fraudulent phishing emails seeking passwords and other confidential organizational information from its staff. And at one point, documents insulting the government were thrown over the wall into the CCHR office by an anonymous actor.

In 2018, I received a summons to appear as a witness in the case of Kem Sokha, who was at the time being held in pre-trial detention. Four officials, one of whom was in police uniform, delivered the summons to my home. In June 2018 I had to appear for questioning at the Phnom Penh Municipal Court, where I was questioned for approximately 1.5 hours by the investigating judge. I still don’t know if I will be required to provide more evidence in the future.

The restricted environment that CSOs such as CCHR operate in, which includes intimidation and harassment such as this, and frequent interference, makes it very difficult for us to effectively do our jobs, as they cannot be done without fear. Despite this, we continue to operate with strength and integrity, enabling the organization and its staff to remain principled and optimistic.

Sao Phal Niseiy: How do you see the current human rights situation in the country taking into account the existing problems such as rights restriction, arbitrary arrests and other activities that affect people’s rights and freedoms?

Chak Sopheap: The current human rights situation in Cambodia is extremely concerning. In recent years, we have witnessed an ongoing crackdown on the exercise of fundamental freedoms, particularly on dissenting voices such as human rights defenders, political opposition, and independent journalists, which has dismally weakened the civic space.

To illustrate, in 2020 alone, we have seen many people arrested for exercising their freedom of expression. This has included an upsurge of people arrested for sharing information online and social media, including those arrested for sharing “fake news”, and threats against women for their clothing choices. Journalists have been arrested for their reporting, and media licenses have been withdrawn, resulting in media outlets being shut down. Prominent union leader Rong Chhun was recently arrested for legitimate expression about the Cambodia-Vietnam border, and those calling for his release, exercising their right to peaceful assembly, have been restricted, arrested and subject to violence.

In addition to this, many workers have been hit hard by COVID-19 and forced into unemployment essentially overnight, with limited accessibility to government assistance and a recorded weakening in labor rights. Land disputes and forced evictions are still occurring, and many marginalized groups, including women, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) individuals, indigenous communities and more are still regularly discriminated against. There have also been worrying legal developments, including the promulgation of the Law on the Management of the Nation in a State of Emergency and the recently proposed draft Law on Public Order, which would effectively criminalize a wide array of individuals for everyday activities if passed.

The Royal Government of Cambodia is facing consequences for its disregard for human rights, and the international community will not stand by this anymore. For example, the European Union decided to partially withdraw the tariff preferences granted to Cambodia under the Everything But Arms (“EBA”) trade agreement in February 2020, citing Cambodia’s serious and systematic violations of international human rights principles, which came into effect on Aug. 12, 2020. While the extent to which the partial EBA withdrawal will affect specific industries is still to be fully realized, it is expected to have a significant impact on Cambodia’s export-driven economy, as the EU is one of Cambodia’s largest trading partners. Cambodia’s economy has already suffered heavily due to the economic ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is likely that this economic downturn will be compounded with the impact of the EBA withdrawal.

A key concern is the effect this will have on the livelihoods of many Cambodians and their labor rights in the country. The EU has stated that if Cambodia shows significant progress, the Commission may review its decision and reinstate trade preferences. The government has the power to reverse the EBA withdrawal and the trajectory of our economy through respecting human rights, and yet has continued the crackdown.

In short, the human rights situation at present is exceptionally alarming, and prioritizing the promotion and protection human rights is as important as ever in Cambodia.

Sao Phal Niseiy: To you, how can we address these issues effectively?

Chak Sopheap: As illustrated by the examples above, the human rights issues facing Cambodia today are innumerable and varied. This means that we need to take a number of approaches to address these issues. Firstly, it is important to educate and inform the community on their rights. A core part of our work at CCHR is raising awareness of human rights amongst the community and how individuals can address human rights abuses they face and support them to seek assistance. It is also crucially important to seek to hold the Royal Government of Cambodia accountable for human rights abuses within the country, and encourage them to take steps to improve the situation. This requires us to mobilize and speak out on human rights concerns and abuses, and engage strongly in advocacy.

Sao Phal Niseiy: How do you view our people’s perception and attitude toward the concept of human rights in general and the LGBT rights in particular?

Chak Sopheap: I am hopeful that attitudes towards and people’s perceptions of LGBTIQ individuals are starting to change for the better. Society is more accepting of LGBTIQ people and are generally supportive of ensuring their human rights. Nonetheless, this can contradict societal and cultural norms, which carry stereotypical preconceptions, and the LGBTIQ community in Cambodia face significant stigmatization and discrimination. For example, while people may be accepting of LGBTIQ individuals from a distance, they aren’t so much within their own families. It is crucial that we continue to work to change this. This includes by strengthening our legal system to recognize and protect the rights of LGBTIQ individuals. But it is also important that we continue to educate the community on this to change further public perception, and promote the rights of LGBTIQ individuals and not ignore discrimination when we see it.

Another area where public perception is key is that of women’s rights. Traditional gender norms are prevalent in Cambodian society, and women are often taught to be submissive, and not to be involved in politics or representing their community. There is pervasive gender-based violence, and a culture of victim-blaming. In recent months we have seen the policing of women’s bodies and clothing from the highest levels of government including the Prime Minister, belittling women’s rights to bodily autonomy and self-expression, and placing blame on women for the gendered violence committed against them. Women have been subjected to threats and imprisonment for their choices in clothing, with one woman convicted of a crime related to her clothing already in 2020, and there is the potential that if the recently released draft Law on Public Order is passed, discrimination against women in this manner will be exacerbated.

This is incredibly problematic, and we must continue to champion women’s rights and change these patriarchal norms. I do have faith that attitudes and public perceptions towards women are slowly changing. From an intersectionality lens, emerging leaders are challenging the traditional hurdles to leadership. New leaders are not only challenging gender roles, but also prejudices stemming from social classes, age, orientations and other marginalized statuses, and I am therefore not so worried about the future generation.

Sao Phal Niseiy: Are you optimistic about the future of Cambodia’s human right situation?

Chak Sopheap: At present, the future of the human rights situation in Cambodia seems gloomy. There is a restrictive legal environment that prevents full participation from those seeking to protect human rights, as civil society organizations operate in constricted civic space, and individuals are hindered from exercising their fundamental freedoms. Moreover, the political structure is not conducive to government accountability, as we have a de facto one-party state, with no strong political opposition remaining. However, I am still optimistic. Our growing youth and citizens, who are increasingly informed, represent a glimmer of hope, and I am confident that more informed citizens can be agents for change, holding the government accountable for a brighter future for human rights.

Sao Phal Niseiy: As the most prominent human rights head, you have inspired many Cambodians and non-Cambodians with your utmost efforts to promote and protect human rights, what is your message for young Cambodians?

Chak Sopheap: Be who you are and pursue your dreams. Bend for them if you need to. Young Cambodians are at an advantage because you are so dynamic and full of potential. Actively participate in the society as the agent of change for the better Cambodia. It’s a matter of time, sometimes slow, but we keep hoping and doing our role. We need to respect each other’s roles. Do your role, respect each other’s role and find a way to collaborate to improve development of this country.