Inside Cambodia’s Anti Children Sexual Exploitation Police Unit

- By François Camps

- April 19, 2022 10:49 AM

Through concrete examples, the author of this book recounts the incredible journey that saw the creation and growth of a very specific unit in the Cambodian police

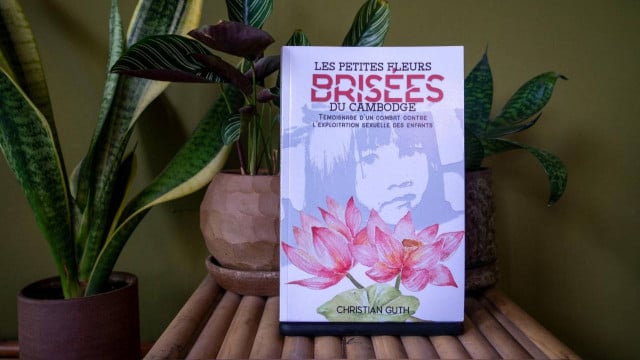

Christian Guth worked for six years as a police commander at the French Embassy in the 1990s. As his mission ended in the early 2000s, he established, in partnership with UNICEF, the NGO World Vision, and the Cambodian Ministry of Interior the “[l]aw enforcement project against sexual exploitation and trafficking of children,” which was the first Cambodian police unit dedicated to the protection of children. The now-retired policeman has just published a book, entitled “Les petites fleurs brisées du Cambodge—literally, “The Little Broken Flowers of Cambodia”—in which he tells the fight his team led to arrest pedophiles in Cambodia.

François Camps: Can you please explain the title of the book?

Christian Guth: In the 1990s, there used to be a slum in the streets right behind the French embassy. At that time, everyone knew that the place was one of the city’s hotspots for prostitution. And some of the prostitutes were very young, still in their early teenage years. People used to call this area “the little flowers’ street”, in reference to the girls one could find there.

Although it is a figurative title for a book, I think it greatly highlights the phenomenon of child abuse: Children are innocent and fragile human beings, just like a flower. If you abuse them, you’ll break them and destroy their lives and future. Just like broken flowers, some will stand up again and keep on living… but some won’t.

I wanted this book to be an account of what I and my team lived when we first launched this project, describing actual criminal cases we faced, but also describing the achievements and failures we’ve been through. So, focusing on the main protagonists, the children, to name the book [after them] was the right thing to do.

François Camps: Establishing a police unit targeting child abusers in the early 2000s must not have been an easy task. What challenges did you have to face? And what helped you succeed?

Christian Guth: At first, no one believed we could set up a police unit dedicated to fight against the sexual exploitation of children. Private interests were so high in such a field: Some police and military officials, or even some politicians were involved in the prostitution business, which sometimes included the exploitation of children. This was a sizable challenge. Then, we knew that it would take time to achieve our first results. We were starting from scratch, with no trained staff to deal with sexually exploited children. The road ahead was long, and donors could have pressured us if we didn’t achieve our first results fast enough. Finally, we also had to deal with the pressure from foreign embassies in Cambodia. When one of their citizens were involved in a case of pedophilia, foreign embassies tended to offer them their protection so they wouldn’t be convicted in Cambodia. This was an obstacle to our mission.

On the other hand, I had a strong knowledge of the field thanks to my previous missions at the French Embassy. I personally trained every manager of the Cambodian national police at that time and knew who would be interested and motivated enough to fight that curse. The result speaks for itself: Twenty years later, the unit still exists!

François Camps: Some passages of the book are coarse, explicitly describing the corporal punishments inflicted on children. Was it important to you to precisely depict for readers what the victims were going through?

Christian Guth: Absolutely, one must call a spade a spade. To comprehend what we were fighting against, the reader has to understand what kind of tragic events children being abused were going through. The difficult part was to describe things without getting too coarse or using inappropriate language. I didn’t want to fall into voyeurism or getting morbid. And I think I found a balance between some crude stories and some others, much easier to read.

Obviously, some passages remain difficult to read. But it’s nothing compared to what these children had lived through.

François Camps: The book mostly put the spotlight on criminal cases involving westerners. But you also write, in the prologue of the book, that there was an important demand for children among several Asian communities, including Cambodians. Who was more involved in pedophilia?

Christian Guth: Based on my experience, I would say that the number of children sexually abused by westerners represented around 10 percent of the total. The rest were committed by Asian communities or Cambodians.

But the reason why the book tells more stories involving westerners is simple: Cambodians were more difficult to apprehend. Many stopped their activity before getting arrested or receiving information that we were investigating them. Globally speaking, it was harder to wrap up an investigation involving Cambodians, although we did arrest many of them over the years.

Another reason is sort of political. If we had arrested numerous Cambodians in the first years, the police directorate would have thought that we were only chasing local criminals, while western pedophiles were [mentioned] in every newspaper. Somehow, we had to find a balance with the Cambodian authorities and make concessions by focusing more on sexual tourism involving children, and the all sorts of traffics attached to it.

François Camps: When it comes to sexual exploitation of children, what is the situation in Cambodia today? Are sex criminals able to operate as freely as they used to in the early 2000s? What role does the internet play nowadays?

Christian Guth: First, I would like to underline that the service dedicated to the fight against sexual exploitation and trafficking of children hasn’t disappeared. And some provincial units that used to have limited capacities have now been reinforced. Moreover, I know that they opened a dedicated service to fight against cybercrime.

Is it enough to say that the problem has disappeared? Of course not. Criminals will always find a way. But what used to be a Far West, lawless land for pedophiles in the 2000s no longer exists. Back then, people could sexually abuse children with almost no risk of getting into trouble. This is not possible anymore.

François Camps: Will the book be translated into English?

Christian Guth: Absolutely. The translation is currently on the way and the English version should be published by the end of the year.