International Labor Day: No Positive Change in Labor Conditions

- By François Camps

- May 2, 2022 2:25 PM

Establishing a national minimum wage in every sector of the economy, and guaranteeing decent living conditions is what unions are advocating for. But there’s still a long way to go.

PHNOM PENH – Khun Tharo, program manager at the Centre for Alliance of Labour and Human Rights (CENTRAL), shared his views on the labor and employment environment in Cambodia, during the celebrations for the International Labor Day on May 1.

François Camps: Today marks the third “International Labor Day” since the COVID-19 pandemic started. What consequences on labor and employment the health crisis had in Cambodia?

Khun Tharo: The pandemic had huge social and economic impacts on workers, in both the formal and informal sectors. If you look at the government data, around 1.5 million workers saw their livelihood decrease because of the crisis. But civil society organizations and union groups estimate this number is more likely around 3 million workers, as a result of factory closures, lay-offs in restaurants, hotels, and the general slowdown of the economy. Because of the lockdown, April and May 2021 were particularly harmful for informal workers.

Most of the time, laid-off people didn’t receive the financial compensations they should have received, as guaranteed by law, such as the seniority indemnity for garment workers. Therefore, most of the workers were unable to pay for their basic needs, their kids’ education or for their medical expenses. And as they had no choice, many of them had to take out loans, sometimes to pay back pre-existing debts, paving the way for over-indebtedness.

During that period of time, there was hardly any social support from the government. From a labor perspective, the suffering and the starvation of the poorest is a clear indicator that the government hasn’t brought an appropriate response to the crisis.

François Camps: The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank economy forecasts are optimistic for the years 2022 and 2023, with 4.5 and 5.3 percent estimated GDP growth respectively. Do you expect positive impacts on employment in Cambodia?

Khun Tharo: It seems that many sectors, apart from tourism, are getting back to pre-pandemic levels of activity. Garment and footwear factories started to reopen from the second half of 2021 with significant exports to the European Union and the United States. As for the construction sector, its activity is stable, with the reopening of real estate projects previously canceled because of the pandemic.

But if you look beyond the economic recovery, the problem has to do with the repartition of wealth. A growing GDP doesn’t necessarily mean that the livelihood, the well-being and the social economic environment of the workers are improving.

Even though workers have now been rehired in their factories, many have lost significant amounts of money, because they had to self-sustain themselves for a long period of time.

This is the reason why, I’m advocating, along with unions’ representatives in Cambodia, for the instauration of a national minimum wage that would guarantee and insure the dignity and livelihood of the workers in every sector. So far, Cambodia only has a minimum wage for workers in garment, footwear and travel goods sectors. It doesn’t cover enough fields and its value ($192 a month) doesn’t guarantee a decent livelihood. We would like to establish a $360 a month minimum wage, covering all sectors.

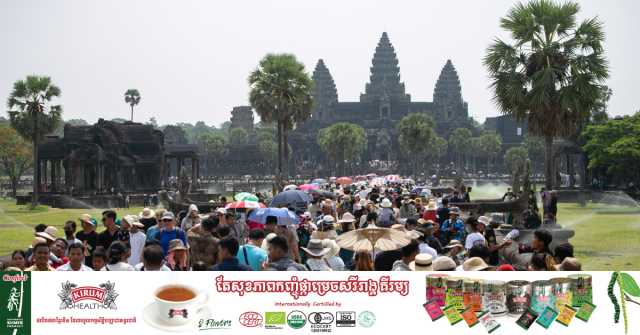

François Camps: The tourism sector, which accounts for 20 percent of the Cambodian economy and provides jobs for more than 1 million people, has been heavily impacted by COVID-19. Can we expect a quick reemployment in this sector?

Khun Tharo: People who used to work in hospitality are still waiting to start their careers back, as most of them didn’t take serious jobs in the meantime.

But, unlike the other sectors we already mentioned, the tourism industry relies heavily on international visitors who don’t seem to be rushing to visit the country. The ease of travel restrictions is a move in the right direction, but as long as there are no major improvements at the global level, hospitality will be impacted in Cambodia. A complete recovery could take up to two years.

François Camps: NagaWorld’s strike has been ongoing for more than four months now, with no end in sight. Is this another example that unions are still threatened and not guaranteed in Cambodia?

Khun Tharo: I would say that the space to assert fundamental freedom of association is significant for the Cambodia labor movement to grow, to nourish. However, the civil rights and political rights have been constrained, restricted in the last couple years and so have the activities of the independent labor movements. They lose significant amounts of their memberships. They cannot sustain their operations or function as organizations because many of their members lost their jobs. So, unions were unable to use their rights, to represent, to defend and to protect their members’/the workers’ economic interests and benefits.

In the case of NagaWorld for example, the strike was the only way left to leverage or pressure the employers or the government to settle their case. That’s the only way because they’ve followed every legal procedure in compliance with the law. But still, the courts have been used to undermine the movement, to justify systematic violence, to suppress the freedom of association. I think these are real threats for independent trade unions.

To this day, some of the prominent union leaders are still facing criminal charges against them. Like Keo Thay or Sun Thun who were arrested without warrant during the pandemic. Older cases, like Rong Chhun’s one, show that union leaders remain harassed and oppressed.

François Camps: Are there new trends when it comes to migrant workers, which account for about 3 million Cambodians working overseas?

Khun Tharo: Nothing is changing. We have been advocating for so many years, including during International Labor Day events, for migrants to have the right to vote. It is crucial, especially during electoral years like 2022 and 2023.

It requires political will to make changes in this matter. But so far, the National Election Committee has been turning down our recommendations to make amendments to the Election law to allow migrant workers to vote. There are almost 3 million migrant workers in different countries and most of them are at the age to be eligible to vote. But they can’t vote because the law doesn’t allow them to vote from overseas.

While the government acknowledges them in terms of remittances, of their contribution to the Cambodian society and economy since they send money home and pay direct and indirect taxes to the Cambodian government, they lack access to voting rights. But Article 36 of the Cambodian constitution clearly emphasizes the right to vote, so the government has to ensure the access of its citizens to this right.

François Camps: We underlined a lot of negative trends in the Cambodian labor environment. Have there been some positive changes?

Khun Tharo: There’s been little to no positive change regarding labor conditions in the past years. I think it’s even more stringent on laborers. However, I do see a little bit of progress in terms of policy frameworks toward the social protection coverage with the National Social Security Fund (NSSF). The law has been adopted but still there’s a lot of work left to be done regarding its coverage policy or expanding the social protection to other sectors such as construction.

I would say that having the law enacted is positive, but its enforcement must be improved. I think about 70 to 80 percent of the total population is not covered by the NSSF, which is a significant amount. And if you look at the national budget, a very small share of it was invested in the NSSF scheme.