Opinion: Don't Lose Sight of Monkeypox as There Are still Unknowns

- By Sonny Inbaraj Krishnan

- September 19, 2022 12:55 PM

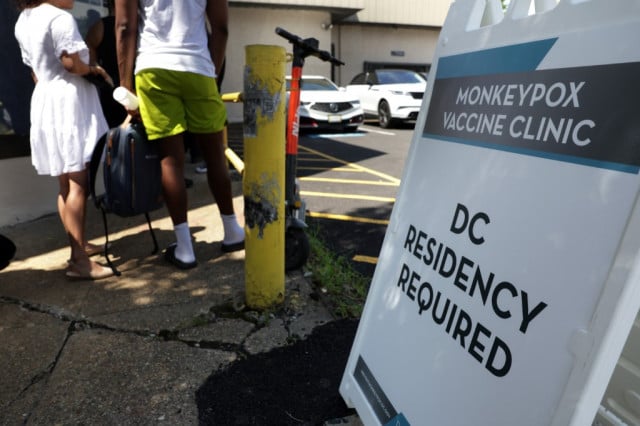

Though the global case count of monkeypox seems to be on a downward trend, it is too early for optimism as there is still ongoing transmission in certain countries in the Americas.

As we go into the next phase of the disease transmission, harsh realities have been brought forth. Unfortunately, there are still numerous unknowns in monkeypox disease transmission, and researchers need to deal with these knowledge gaps to be better prepared for the next wave of outbreaks.

While it is clear that the current epidemic is driven by close intimate contact between sexual partners, it's less clear how people without symptoms can infect others.

In many developing countries, vaccines are still unavailable, and information on how to avoid infection hardly reaches groups of people most vulnerable to monkeypox. In addition, most confirmed monkeypox cases are among men who have sex with men. In countries where gay sex is criminalized, there is fear of recrimination if such information is sought.

There have been 61,282 cases and 20 deaths as of 16 September 2022, across at least 96 countries, according to the US Centers for Disease Control. On 23 July 2022, the World Health Organization declared monkeypox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Between 5 September and 11 September, there were 4,009 confirmed cases globally compared with 5,029 cases between 29 August and 4 September. This represents a 20.2% drop in monkeypox cases worldwide.

"We're continuing to see a downward trend in Europe. While reported cases from the Americas also seemed to drop, it is harder to draw firm conclusions in the epidemic in that region," the World Health Organization Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told a virtual media conference on 7 September.

"Some countries (in the Americas) continue to report an increasing number of cases, and in some, there seems to be underreporting due to stigma and discrimination or a lack of information for those who need it most," he added.

"But a downward trend can be the most dangerous time. It opens the door to complacency," warned Dr Tedros. The WHO is concerned that as the epidemic wanes, so will countries' response to control the spread of the disease.

Monkeypox was first diagnosed in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and soon appeared in 10 African countries.

The disease, according to WHO, has historically been reported in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Ghana (identified in animals only), Ivory Coast, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan.

Monkeypox can infect a wide range of mammalian species. Still, scientists are yet to exactly pinpoint its reservoir – though there is evidence that squirrels and other types of rodents can naturally harbour the virus.

Human monkeypox cases occur when there is an interaction with these infected animals. Most of them arise from zoonotic spillover – with the virus crossing over from an animal to a human when humans invade jungles and forests, the natural environment of the animal reservoir.

Even though the monkeypox virus has circulated for decades in certain African countries, research into monkeypox was neglected and underfunded. As a result, monkeypox outbreaks in Africa are rarely reported, leading to an incomplete picture of the disease's importance and never receiving appropriate attention to prevent it from becoming an epidemic.

Earlier fragmented research mainly was in rural communities where the disease transmission was from animals to humans. In 2022, researchers were at a loss when cases started appearing globally in urban areas, with human-to-human transmission in countries where the disease was not previously seen. It seemed they were starting from zero, even though monkeypox is not a new disease nor a novel one.

Also, monkeypox's spread in non-endemic countries has led many to wonder if, like SARS-CoV-2, the virus has mutated to allow for easier human-to-human transmission. New research suggests the monkeypox virus has acquired an average of 50 new mutations compared to strains detected from 2018-2019. This is roughly 6-12 times more than the expected 1-2 mutations per year. Researchers think this "accelerated evolution" could be linked to the virus adapting to evade the host's immune response to fight infection.

Scientists are also worried that sustained human-to-human transmission of monkeypox worldwide could see the virus move into high-risk groups, like pregnant women, immunocompromised people and children.

Children can catch monkeypox if they have close contact with someone with symptoms. Data from previously affected countries show that children are typically more prone to severe disease than adolescents and adults.

Although information regarding the effects of monkeypox infection in pregnant women is scarce, the transmission of monkeypox has been associated with fetal death and congenital infection. Congenital infections affect the unborn fetus or newborn infant. They are generally caused by viruses that may be picked up by the baby at any time during the pregnancy up through delivery.

The neglected research on monkeypox has also affected vaccines currently used against the disease.

The Jynneos vaccine, approved by WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control, was first used against smallpox. However, on 8 May 1980, WHO declared the world free of smallpox, which led to a cessation of the use of vaccines against the smallpox virus. The use of Jynneos against monkeypox is based on an observational study involving 245 people infected with monkeypox in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) between 1981 and 1986 and more than 2,000 of their contacts.

The results indicated that individuals who had a visible scar from a jab with the first-generation smallpox vaccine were about seven times less likely to contract monkeypox after exposure to an infected person than those who were unvaccinated. However, other than these observational and human safety studies, there have not been any significant clinical trials to evaluate the vaccine's efficacy against monkeypox.

Another pressing problem is that the Jynneos vaccine, manufactured by Bavarian Nordic, is in short supply. The catch is that Denmark-based Bavarian Nordic is the sole manufacturer of the Jynneos vaccine. Analysts are sceptical that the company can produce enough supplies to match up against the likely worldwide need.

With monkeypox, we are now seeing a COVID redux in Africa where at a certain period in 2021, more than 80% of people in Africa had not yet received a single dose of any vaccine. Africa is the only continent where monkeypox is endemic and has yet to receive vaccines for the virus as the infectious disease spreads worldwide. With improved transportation in Africa, there is an increased global threat of zoonotic pathogens like the monkeypox virus traveling to large urban centers.

The 19th-century military theorist Carl von Clausewitz coined the term "fog of war" to describe uncertainty when militaries fail to understand their enemy's strength. What we're facing now with monkeypox is a fog in a public health emergency. We seem to be swimming in epidemiological data without fully understanding the virus's behaviour and how it affects at-risk populations.

Our failure to grasp these uncertainties could contribute to a public health failure if we allow complacency to creep in, as WHO's Dr Tedros puts it.

Sonny Inbaraj Krishnan is Internews Regional Health Advisor for COVID-19 for Asia and a Pandemic Health Journalism mentor. Internews works with a network of global journalists and partners responding to health crises.