Opinion: Peace and Democracy in Cambodia—Reflections of a Friendly Observer

- By Christian Berger

- October 27, 2021 9:53 AM

German Ambassador Christian Berger shares his “glass half full” view on Cambodia’s progress regarding peace and democracy following the signing of the Paris Peace Agreements

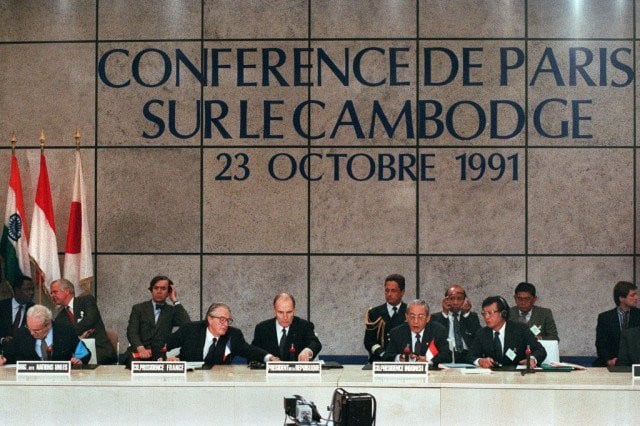

On Oct. 23 it was 30 years that the Paris Peace Accords were signed. A reason to celebrate or a time to quarrel?

I am convinced that we all, Cambodians and “others,” have good reasons to celebrate: Just like the “2+4-treaties” opened the path for German reunification and provided the German nation and all of our European neighbors with a new and positive perspective, the Paris Peace Accords led Cambodia out of the dead end street marked by the years of unprecedented terror of the Pol Pot regime and another decade of Cambodia being caught between the millstones of the East-West-Confrontation.

The signing of the Paris Peace Accords opened the way to an equally unprecedented engagement of the United Nations and the whole international community, including recently reunified Germany, to help rebuilding a country crushed by decades of internal and external conflicts. The active and focused cooperation by a multitude of actors, namely multilateral agencies, governments, and civil society, both national and international, for over now three decades made Cambodia a true economic success story: The country has reached the status of a lower middle-income country. And this growth has been increasingly inclusive, meeting most UN Sustainable Development Goals criteria and thus scoring better than many other countries.

This cooperation also proved its worth when COVID-19 struck. In particular, the ID-Poor scheme based on years of development assistance by Germany and various other actors including UN agencies, Australia, and Sweden, provided an effective mechanism for providing help to the poor.

The figures reveal the strategic importance of this tool in mitigating the effects of COVID-19: 610,000 households or 2.8 million people were covered by the scheme in July 2021.

And after COVID-19? I do not pretend to have an overview of all initiatives, but let me use my own country as an example for the continuing relevance of cooperation schemes for Cambodia: Germany is working on sectoral policy inputs for the post-COVID economic recovery, and together with our Swiss friends we are supporting the Ministry of the Interior on decentralization. I consider both fields highly relevant.

There is no doubt: The cooperation triggered by the Paris Peace Accords was instrumental in bringing Cambodia forward. But in my eyes, besides this systematic cooperation effort involving the international community, there were at least two more equally necessary ingredients to this long-term economic success:

One is the win-win policy based on the Paris Peace Accords. Its implementation allowed to overcome some of the deepest rifts in Cambodia’s society.

The other one, again based on the Paris Peace Accords and the negative experiences of the past, consisted in the establishment of a constitutionally guaranteed multi-party democracy and a lively civil society, free labor unions, and media which have something worthwhile to report and to reflect on. In my eyes, these elements of a political framework have provided Cambodia with a competitive advantage.

And yet, the judgement where Cambodia really stands 30 years after the PPAs is far from uniform. There is not even the typical discussion about the glass being half full or half empty. Rather than that, the views that are given these days often seem to differ fundamentally.

One reason could be that different actors attach different importance to the relevance of the three ingredients I mentioned. As far as I am concerned, while I do not hide my pride about the successful German contributions to Cambodia’s growth in the past three decades, I am very much aware that these types of contributions alone would never have done the trick. The three ingredients in my eyes are complementary, and Cambodia’s success can only be explained by this triple combination. As a German citizen, allow me once more to draw the comparison between Cambodia and Germany: I know from my own experience about the complexities, the difficulties, and the duration of the process of German reunification. While the problems in Cambodia may have been of a different nature, their complexity certainly was of a similar degree, and the necessary time frame for dealing with this complexity should not be underestimated.

It seems to me that in everyday politics in Cambodia, multi-party democracy, the strong civil society, the free unions, and the independent reporting by the media are not always recognized for what they really are, namely assets for the Cambodian society.

Let me give an example to explain what I mean: The establishment of red zones to combat the spread of COVID-19 was no doubt necessary. In the implementation, there were shortcomings in the beginning, as was to be expected in a complicated scheme never tried out before. But when the media reported on shortcomings, and when people interviewed voiced their grievances, the reaction was, at least to a certain extent, to label this criticism as “opposition.”

One reflection on the importance of civil society: Civil society and government institutions are not always natural partners. But both should recognize that in a modern 21st century society, each of them has a role to play. One field where there has been productive interaction was microfinance. It was the call by the 103 civil society organizations that triggered action by the authorities to address the microfinance lending crisis. Be it in microfinance or other sectors, I hope that civil society organizations on the one hand will go beyond whistle-blowing, and that government institutions on the other hand will go for a constructive cooperation with civil society. All actors have their roles, sometimes their goals do not match, but all actors should understand their roles as complementary for the functioning of the Cambodian society and act in the national interest.

In this context, the legal basis for a productive functioning of civil society needs to be defined in a solid way. Now that COVID-19 no longer is an obstacle, I am looking forward to restarting the discussion on the Law on Associations and NGOs (LANGO). A viable compromise on LANGO would also pave the way for a constructive discussion on the draft law on establishing an independent National Human Rights Institution.

I am well aware that all this is a part of a process demanding more than expertise and billions in aid money. Namely, it requires the constant will to keep reforming the country’s political thinking. It requires the will to cooperate, including on issues where opinions differ. It requires the willingness to compromise and to put the national interest above other goals.

I see the decentralization reform, aiming at changing attitudes of bureaucrats as well as of citizens, as one important practical ingredient to this process. I am proud that the Royal Government of Cambodia has chosen Germany as one of Cambodia’s partners in this field.

Cambodia has gained international recognition for applying tools such as the Universal Periodical Review process in Geneva and the work of the OHCHR office in Phnom Penh, to tackle specific subjects in cooperation with all interested national and international actors.

In my eyes, this makes it clear that the Royal Government of Cambodia does not view its commitments regarding human rights as mere formalities but is willing to work on the substance, even when this means having to consider different points of view. This commitment, by the way, also makes me hopeful with regard to the upcoming election that it will still be possible to provide for a functional opposition as part of a thriving multi-party system. In my eyes, this is not only a technical matter, but an essential element for accomplishing the great goal of national reconciliation.

The present discussion about the meaning of the Paris Peace Accords also has a foreign policy dimension that tends to make things more complicated. Again, going back to the Paris Peace Accords could be helpful in finding common ground: It was on the basis of the discussions following Paris that article 53 was included in the Cambodian Constitution, stating that “the Kingdom of Cambodia adopts a policy of permanent neutrality and non-alignment.”

“No country should be forced to decide between two poles.” This statement by German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas in his capacity as representative of the EU Presidency, made on the occasion of the decision on the Strategic Partnership between ASEAN and the EU, is fully in line with Article 53.

And, in her speech on the Indo-Pacific region delivered on Aug. 24 in Singapore, US Vice President Harris equally underlined that the US engagement in the region is “not…designed to make anyone choose between countries.” These clear statements from important international actors should make it easier for the Royal Government of Cambodia to adhere to article 53 in difficult times.

To sum it up: It is, or in any case it should be, peace and democracy. And yes, when looking at the constitutional framework regarding political parties, the vibrant civil society, the lively unions, and media still able and willing to report, the glass still is half full. Let us all continue working together on filling it up further.

Some of you may consider my approach too idealistic. I simply think that this approach is in the national interest of Cambodia. But in the end, whatever I may think, decisions on Cambodia’s future course will have to be taken between Khmer and Khmer.

Christian Berger has served as Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany to the Kingdom of Cambodia since September 2019