Opinion: We Need Generic Versions of COVID-19 Vaccines for the Poor

- Sonny Inbaraj Krishnan

- November 30, 2020 10:54 AM

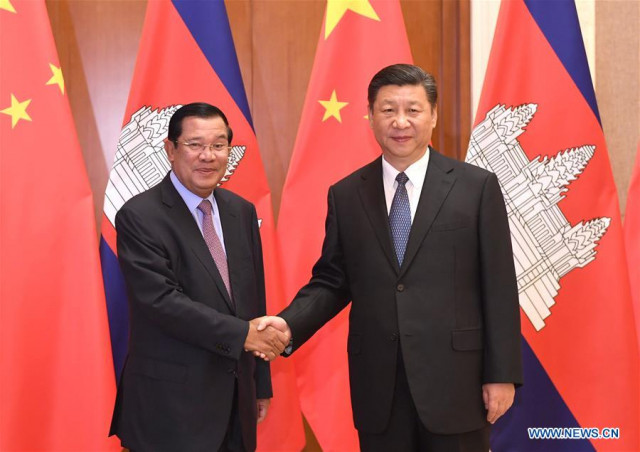

We are far from ending COVID-19 as a public health issue, especially in poor and lower middle-income countries like Cambodia if rich nations get the lion’s share of vaccines and the leftovers are thrown to the less well-off.

Over the past two weeks we have heard some good news in the race to find a COVID-19 vaccine and end the pandemic which globally has claimed nearly 1.5 million lives.

Pfizer and Germany’s BioNTech announced on Nov. 18 that their COVID-19 vaccine has 95 percent efficacy, even better than the 90 percent found in its initial analysis, and they will apply for emergency use authorization from the US Food and Drug Administration. Two days earlier, Moderna announced that their COVID-19 vaccine has 94.5 percent efficacy based on Phase 3 clinical trials.

AstraZeneca, which partnered with the University of Oxford, announced on Nov. 23 that its coronavirus vaccine reduced the risk of contracting COVID-19 by an average of 70.4 percent, according to an interim analysis of large Phase 3 trials conducted in the UK and Brazil.

The term vaccine efficacy is used to measure how well a vaccine works to prevent a particular disease (in this case COVID-19) in controlled, research environments. Vaccine effectiveness studies examine how well a vaccine prevents a particular disease in the “real world” where people are doing things like going to the grocery store, work, and school. If a vaccine has 95 percent efficacy, using an example of 100 trial participants in a given trial of a vaccine, 95 patients would not contract the disease and five would contract COVID-19.

The prospect of preventing illness and death, and avoiding the harm and misery of extended lockdowns, is a cause for optimism. According to local media reports the Cambodian Ministry of Health has set up a special working group to plan for the distribution and storage of a future COVID-19 vaccine once it is approved by the World Health Organization and reaches Cambodia. The health ministry is presently setting up a warehouse in the capital’s Chaom Chao commune where the vaccine can be stored at the proper temperature.

But although it is right to be hopeful and encouraged, we are far from ending COVID-19 as a public health issue, especially in poor and lower middle-income countries like Cambodia.

Why? For one, according to studies done by Duke University in North Carolina there will not be enough vaccines to cover the world’s population until 2022 or even 2023.

Data from Duke University’s Global Health Innovation Centre show that 6.4 billion doses of potential vaccines have already been bought, and another 3.2 billion are either under negotiation or reserved as “optional expansions of existing deals.” According to Global Justice Now’s pharmaceutical campaign to fight for access to medicines in the UK and across the world, more than 80 percent of the Pfizer vaccine stocks up to the end of next year have already been hoarded by rich countries such as the UK, the US, EU members, Japan and Canada. Collectively these countries represent just 14 percent of the global population.

A separate Oxfam report said that even if all five leading vaccine candidates in Phase 3 clinical trials are approved, nearly two thirds of the world’s population will not be vaccinated until 2022. It’s a case of an unfolding scenario where the rich countries will have vaccines and the poorer countries are unlikely to have access. For those in developing countries like Cambodia the long wait can be fatal.

Is there a way out of this crisis? The COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access Facility (COVAX) – led by the World Health Organization, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance—was established precisely to prevent this outcome.

The COVAX Facility aims to accelerate COVID-19 vaccine development, secure doses for all countries, and distribute those doses fairly, beginning with the highest-risk groups. In other words, the facility was created partly to prevent hoarding by rich-country governments.

COVAX’s aim is to buy 2 billion doses by the end of 2021, though it isn’t yet clear whether the successful vaccine will require one dose or two for the world’s 7.8 billion people. Countries taking part in the project can either buy vaccines from COVAX or get them for free, if they are poor.

But herein lies the problem. Given the constraints at work—the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, for example, must be administered in two doses three weeks apart, and only 1.35 billion doses, at most, will be produced by the end of next year. And problems are already emerging: Some of the world’s wealthiest nations have negotiated their own deals directly with drug companies, meaning they don’t need to participate in the endeavor at all.

COVAX and the philanthropic funds to support it are only of any use if a vaccine can be manufactured in sufficient quantities and delivered to enough locations. Currently, this simply does not seem possible.

This global public health emergency, besides killing people, is also threatening livelihoods and pushing millions into extreme poverty. There is a debt crisis on the horizon with many developing countries forced to spend more on servicing existing debts than on their health budgets as supply chains collapse, remittances plummet, and capital outflows reach unprecedented levels.

Indeed, these dire realities demand a swift and decisive response.

In an open letter, 380 civil society organizations urged World Trade Organization members to remove barriers to access for critical COVID-19 supplies. This open letter was in support of a proposed resolution tabled by South Africa and India at WTO’s TRIPS Council to give countries the power to neither grant nor enforce patents linked to COVID-19 drugs and vaccines until global immunity is achieved.

This means that generic versions of the vaccine can be made by developing countries for their populations at the height of the current pandemic.

“A global pandemic is not the time to follow a ‘business as usual’ approach by protecting intellectual property rights and granting monopoly rights to pharmaceutical companies. Instead, governments should take the chance to secure a People’s Vaccine as a global public good,” the CSOs wrote.

Unfortunately, the resolution was blocked on Nov. 20 by the US, the EU and other wealthy nations, succumbing to the strong lobby by big pharma companies that they are entitled to a return on their huge investment in vaccine research and development.

It is inhumane to impose monopolies during a pandemic and the WTO for the sake of humanity should relax intellectual property protections for COVID-19 vaccines.

Let not history repeat itself.

Antiretroviral drugs to treat HIV entered the market in the mid-1990s but the prices that companies set for these drugs put them out of reach for many. As deaths in rich countries plummeted, infected people were left to die across Africa. It is estimated that, between 1997 and 2007, 12 million Africans died waiting for enough life-saving drugs to reach the continent. The drugs’ arrival was largely thanks to the efforts of the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

The developing world is also no stranger to vaccine hoarding. During the 2009 swine flu pandemic, many rich countries placed large pre-orders on vaccines that resulted in fewer available doses left for poorer countries.

We need an approach to health that is rooted in compassion which would help us see beyond ourselves and place the good of others first. Now more than anything else, at this crucial moment in time, we need a careful reflection on how we can save lives with the equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

Sonny Inbaraj Krishnan is Internews Regional Health Advisor COVID-19 for Asia in the Rooted in Trust Project. Internews works globally with a network of partners responding to rumors and misinformation in the global ‘info-demic’.