PHILIPPINES: Students Back in School, Fret about the Pandemic’s Impact on their Future

- By Rassel Meigan Rodriguez | Reporting ASEAN

- September 18, 2022 8:50 AM

MANILA--Rediscovering face-to-face interaction and spontaneity. Navigating technology-related woes, and juggling remote and in-person classes. Facing sharp increases in living costs. Worrying if they missed out on quality education due to the Philippines’ school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic, as graduation time nears.

These are a mix of Filipino students’ experiences in the weeks since universities and colleges began reopening their campuses from late August, 2.5 years after shutting their doors due to the pandemic in this country of more than 115 million people.

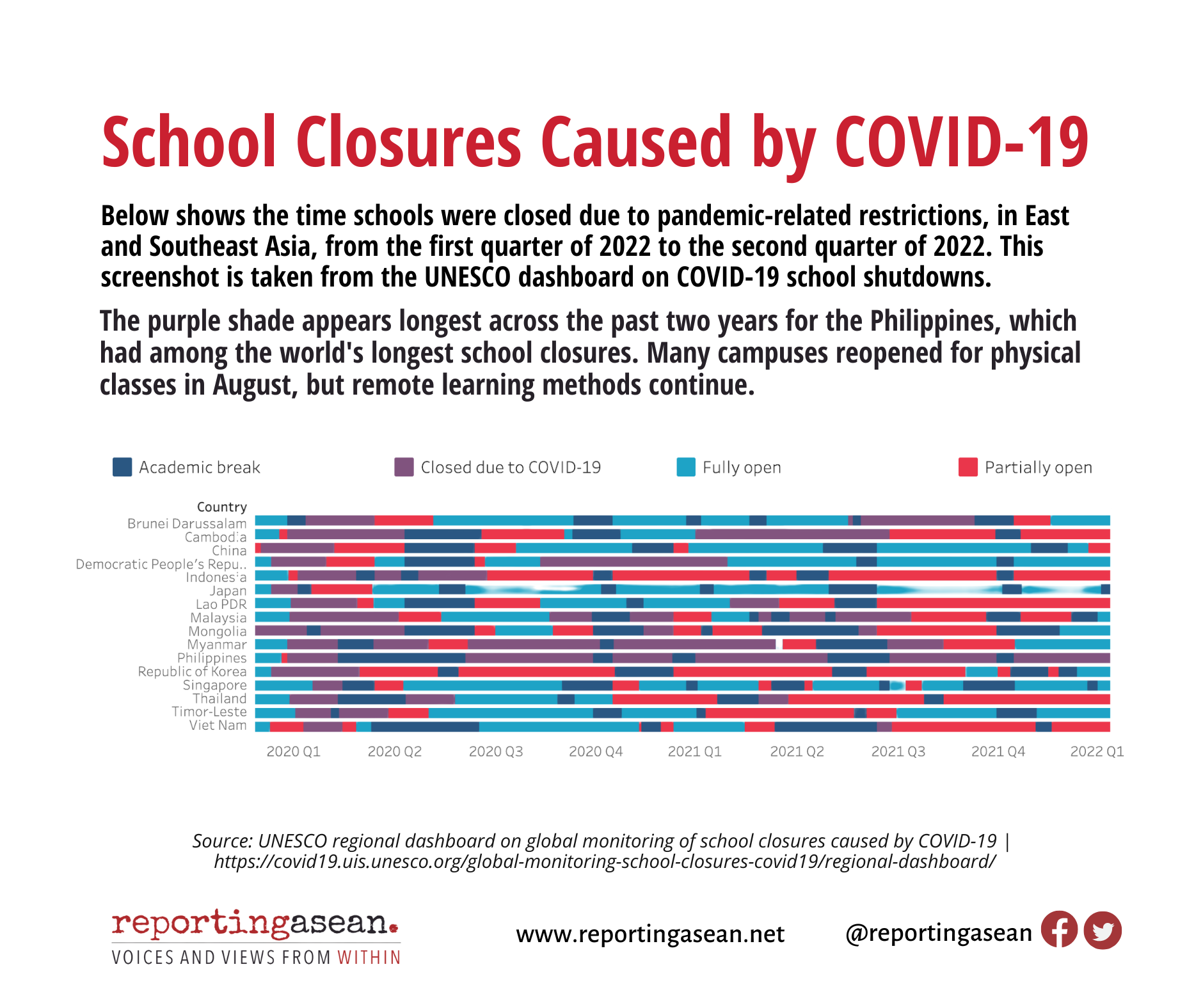

Millions of university students are back in class, whether in person, online or some mix of the two, in this Southeast Asian country that had among the longest school closures in the world. The Philippines was also the last ASEAN country to reopen its schools, which had been fully closed from 15 March 2020 to 22 August 2022, data from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) show.

Psychology major Aline Salillas, 22, is glad to be back on campus, its familiar classroom dynamics and interactions with friends. Her school, Ateneo de Manila University in Quezon City, has been holding mainly on-site classes since 11 August, but has flexible options for students with health-related concerns.

Even the physical tiredness from traveling to and around campus is welcome to Sallilas. “At least, you’re aware that you’re tired,” she shares. “During online learning, you really need to set boundaries

Unlike Salillas, Angel Reyes, who is pursuing a degree in materials engineering, has not yet been commuting regularly to the University of the Philippines, whose classes started on 5 September. This semester will remain mostly online, with some laboratory lessons and examinations in person.

Reyes is both excited and nervous at the thought of this mixed mode of study. “Sometimes, not being able to interact with good professors feels like such a loss,” says the 21-year-old student. “There was so much they could impart [to] me that I wasn’t able to fully absorb, especially if they don’t really record their class.”

Reyes is quite used to remote learning by now, finding technology to be friend – and foe – in a country where internet penetration is at 82% but is of poorer quality than several neighbouring countries. It was an indispensable means of learning for students, but also a source of exhaustion and other distractions during classes. Recorded class lectures and digital learning material like eBooks helped immensely.

The learning situation, however, was quite different for others, including students living outside the capital. Veverly Avance, who is now a freshman in social work at Southern Christian College in southern Cotabato province, found her first year of senior high in 2020 a struggle – and says she had to pull herself up to eventually become an honour student.

“My experience learning remotely … has been the most difficult year of my academic career,” Avance says. “I lost interest in my school activities. I [didn’t] go to subject meetings, since I frequently [ran] into internet problems and [couldn't] afford to [put] load [into] my SIM [card].”

HIGHER COST OF LIVING

While the COVID-19 situation has improved enough to allow a reopening of some campuses, the economic crisis that the pandemic ushered in is far from over. In fact, it has been exacerbated by inflation and rising living costs in the Philippines, in the wake of global instability from the war in Ukraine.

Many university students are finding their relief of going back to a degree of normalcy diminished by worries about the increasing costs of transportation, which have been pushed up by higher global fuel prices, as well as lodging.

The country’s inflation rate climbed from 3% in February to 6.4% in July, which was the highest since October 2018, the Philippine Statistics Authority reported. It eased just a bit to 6.3% in August. Average inflation from January to August was 4.9%, higher than the Central Bank’s targeted range of 2-4%.

The minimum fare for jeepneys, a commonly used mode of public transport, was increased by 1 to 2 pesos (1.7 to 3.5 US cents) to reach 11 pesos (19 cents) in July. Another increase is due in September.

Avance, the freshman in social work, saw her motorcycle taxi fare double from the pre-pandemic rate of 10 pesos (17 cents). She also has to fork out extra for trips during downpours and floods in the current monsoon season.

For her part, Salillas worries about her lodging expenses after moving to a condominium that is nearer her university and cuts her travel time, but has higher rent. Compared to the 15,000-peso (262-dollar) rent that she shared with three other roommates before the pandemic, Sallilas now splits the 16,000-peso (280-dollar) rent with two roommates.

LOST YEARS?

Then there are the larger worries that youngsters have as they become pandemic-era university graduates, including reflecting on whether the remote learning of the past two years has equipped them adequately for the future.

Senior student Samantha de Jesus, pursuing a public health degree at the University of the Philippines, feels “very unprepared” for her post-graduate choices – which may include taking the board examination for medical technology or pursuing a degree in medicine. Limited face-to-face laboratory work at the university restarted only from November 2021.

“I realize I may be graduating soon already, and I don’t think I’m ready to move on to the next chapter of working,” she says. “Along the lines of health, it can mean life or death (for future patients).”

Journalism graduate Christina Quiambao’s dissatisfaction with remote learning prompted her to seek out news organisations to write for – while completing her final year at the University of the Philippines in 2021 – in order to gain more of the skills she now uses as a digital news writer.

“Because of the drawbacks of remote learning, my mental health at work can get affected,” she explains. “You could feel down, thinking, ‘do I deserve to be here, when this is just all that I know?’ ”

These fears are far from surprising given worries about the country’s education system. Prior to the pandemic, the Philippines had the second highest learning poverty rate of 90.9% among nine Southeast Asian countries – just behind Laos’ 97% and Cambodia’s 90%, says the World Bank’s ‘State of Global Learning Poverty’ update for 2022. The Philippines’ figure means that 90.9% of 10-year-olds in the country cannot read and comprehend a simple text.

“What I miss about the classroom is that it’s a sacred space where all is free to speak without judgment,” says University of the Philippines sociology professor Samuel Cabbuag. “Now we have to record things, since not all attend discussions. What if [the student] discusses something really sensitive, and it’s recorded?”

Although the school closures took out the “liveliness and spontaneity” around in-person discussions and collective art experiences, arts instructor Con Cabrera looks forward to adapting some remote methods to face-to-face settings while continuing policies of “empathy” and “reasonable flexibility”.

_1663460881.png)

“Those years challenged how and what we think of traditional ways of teaching, which includes but is not limited to the frequency of lectures, grading systems, and requirements that gauge the students’ learning status of capacities,” explains Cabrera, who also teaches at the University of the Philippines.

Unlike the country’s primary and secondary schools, which began face-to-face classes on 22 August and are required to be holding five days of in-person classes a week by November, universities have room to decide whether, and when, to shift back to in-person classes. They are, however, required to adhere to minimum public health standards.

LESSONS LEARNED

For now, the pre-pandemic chatter of young people out and about is back in some university premises. But remote learning is here to stay, at least for some time, as most universities combine online and on-site platforms.

“I feel like it would be the best of both worlds,” Uean Carlos, a civil engineering student from Mapua Malayan Colleges Mindanao in southern Davao City. Some of his in-person classes also stream online, so “I can come to school for subjects that I deem to be difficult, and for lax subjects, I can stay at home.”

Micah Bacani, who graduated in computer engineering this year, says the pandemic lockdowns do not have to mean missed opportunities. “There are skills that weren’t developed because we were not given access to on-site activities, but I believe that there are also extra skills gained,” he says, including independent learning. “Different experiences give different things learned.”