The Sosoro Museum: Where Learning about Cambodia’s History—through Money—Turns Exciting

- By Michelle Vachon

- December 21, 2022 3:15 PM

PHNOM PENH – Did you know that the oldest currency ever found in Cambodia is a coin minted in the Pyu city-states (in today’s Myanmar) that was used throughout the region for international trade?

Because at the time, that is, in the 3rd through the 6th centuries, trade routes between China, India and countries to the west converged on Funan, as Cambodia was referred to in Chinese chronicles.

“Funan truly was the focal point (or nerve center) of international maritime trade,” said Blaise Kilian, co-director of the Sosoro Museum in Phnom Penh. “A large number of merchants would come to trade: That marketplace was where East met West.” And while there is no proof that merchants from Rome came to Funan, Roman coins were found at Angkor Borei, Funan’s capital, he said.

Funan at the time extended to parts of the Mekong Delta in today’s Cambodia and Vietnam. “We had a society, a kingdom that was wealthy, affluent, refined: Cambodia of 2,000 years ago,” Kilian said.

But around the 5th or 6th centuries, international merchants started to use maritime routes near Malaysia and Indonesia, and Funan refocused its economy on agriculture, and centered on itself, he said.

This and other little-known facts about Cambodia can be found at the Sosoro Museum in Phnom Penh where people from 4 to 84 years old—as the saying more or less goes—will find fascinating and odd details they will be eager to share with friends and family.

There are touchscreens, videos and even games, information one can listen to in Khmer or read in English. And colorful images along with short film segments.

All this is displayed in large rooms in which one has ample space to move without feeling restrained by other visitors who stop to read or watch images or films.

Then without even noticing, people learn about Cambodia’s history going back 2,000 years.

“This is a museum with two particularities,” Kilian said. “First, it’s a museum that presents a global overview of Cambodia’s whole history over the last 2,000 years. And 2,000 years of history from an economic and monetary angle.” In Phnom Penh, the National Museum of Cambodia focuses mainly on the pre-Angkorian and Angkorian era, and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum on the Khmer Rouge regime of 1975 to 1979, he said. “Those two periods are very important for Cambodia, one because it was glorious, the other because it was tragic,” he said. “But there is a great deal more to say about Cambodia.”

Oddly, the Angkorian empire and the Khmer Rouge regime are the two major periods in Cambodia’s history during which there was no money—for entirely different reasons of course, Kilian said. While in power from April 1975 to January 1979, the Khmer Rouge leaders turned the country into a vast slave-labor camp in which no one was paid. As for the Angkorian empire that dominated the region a millennium ago, Chinese records report that people would use barter, that is exchange goods or services, Kilian said. “Which is slightly bizarre considering the complexity of the empire’s administrative system, which was centralized.” However, more important transactions regarding land acquisitions for temples and so on would be done with payments in gold and silver, he said.

Then came the decline of the empire. By the 19th century, the country’s neighbors to the east and to the west were gobbling up its territory, Kilian said. “Cambodia was in serious difficulties at the time and Ang Duong, who was a great king, had decided, among other measures…to issue money.

“He was a very modern king who understood that Cambodia’s sovereignty had to be salvaged,” he said. Among other measures, the king wrote to France’s Emperor Napoleon III, seeking protection against the country’s neighbors. But it is only after his death that his son and successor King Norodom would manage to sign the Protectorate Treaty with France in 1863.

During Indochina, the French administration set up a single currency system to be used throughout the three countries involved—Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Whether that currency was actually used in every city and village of Cambodia, one cannot say, Kilian said.

Still, the launch of this currency unit called “piastre de commerce” (commerce piaster) greatly impacted the three countries’ economy, he said. “This was the first monetary system that was systematic, massive, complete and rational meant to be used throughout these countries’ cities, villages and so on,” he said.

As can be seen at the museum, the Indochina bills were beautiful. “They were illustrated with images that were quite colorful and rather pleasing to the eye,” Kilian said. Featuring elements from the three countries and France, he said, “we see a representation of Asia [and the three countries] that is rather romantic, as it was perceived by the French.” Whether Cambodian, Laotian or Vietnamese people actually related to these images meant to reflect who they were and where they lived remain to be seen, Kilian said.

When Cambodia gained its independence in 1953 and Indochina was dissolved in 1954, France suggested to keep this shared currency. “Indochina’s countries refused because they had grasped that money was an instrument of sovereignty,” Kilian said. “So that currency alliance had to be eliminated, which proved no simple matter.”

And then, replacing that system by each country’s own was no simple matter either, he said. However, Cambodia had many experts and business people with the knowledge and experience to do so. Prince Norodom Sihanouk as head of state would turn to them to launch the country’s currency—the riel—and build confidence in it so that it would be accepted and used throughout the country and internationally. Among them was Son Sann who had studied at the business university École des Hautes Études Commerciales in France and would serve as governor of the National Bank of Cambodia from 1955 through 1968.

A young visitor, left, is using an audio handset to learn about this piastre reproduced in large format. The piastre was the currency when Cambodia was part of Indochina in the late 19th century and the first part of the 20th century. Photo: Sosoro Museum

A young visitor, left, is using an audio handset to learn about this piastre reproduced in large format. The piastre was the currency when Cambodia was part of Indochina in the late 19th century and the first part of the 20th century. Photo: Sosoro Museum

As can be seen at the museum, the riel notes of that era featured beautiful scenes and major elements of life in the country ranging from rural life and religion to the Royal Palace and the Royal Ballet. However, King Norodom Suramarit and Prince Sihanouk do not appear on riel bills, Kilian noted.

Then came the years of turmoil: the Khmer Rouge regime of 1975-1979 and the civil war in the 1980s. The Paris Peace Agreements would mark the official end of war in 1991, and lead in 1992 to the peacekeeping mission of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), which used US dollars as currency.

What happened between the end of the Pol Pot regime in 1979, and the surrender of the last Khmer Rouge leaders in late 1998 can be seen at the museum in a series of panels that highlight key events during those two decades that ended with the surrender of the last Khmer Rouge leaders and the start of peacetime throughout Cambodia.

Today, the Cambodian authorities are working at making the riel more widely used in the country and, already, this currency is accepted more readily than it was 10 or 20 years ago, Kilian said. “This is being done with great subtlety because the National Bank understands that this is based on trust,” he said. “Since 1993, the position taken in the economy is that one must not disrupt market mechanisms…and so to progressively make people aware of and put trust in the riel.”

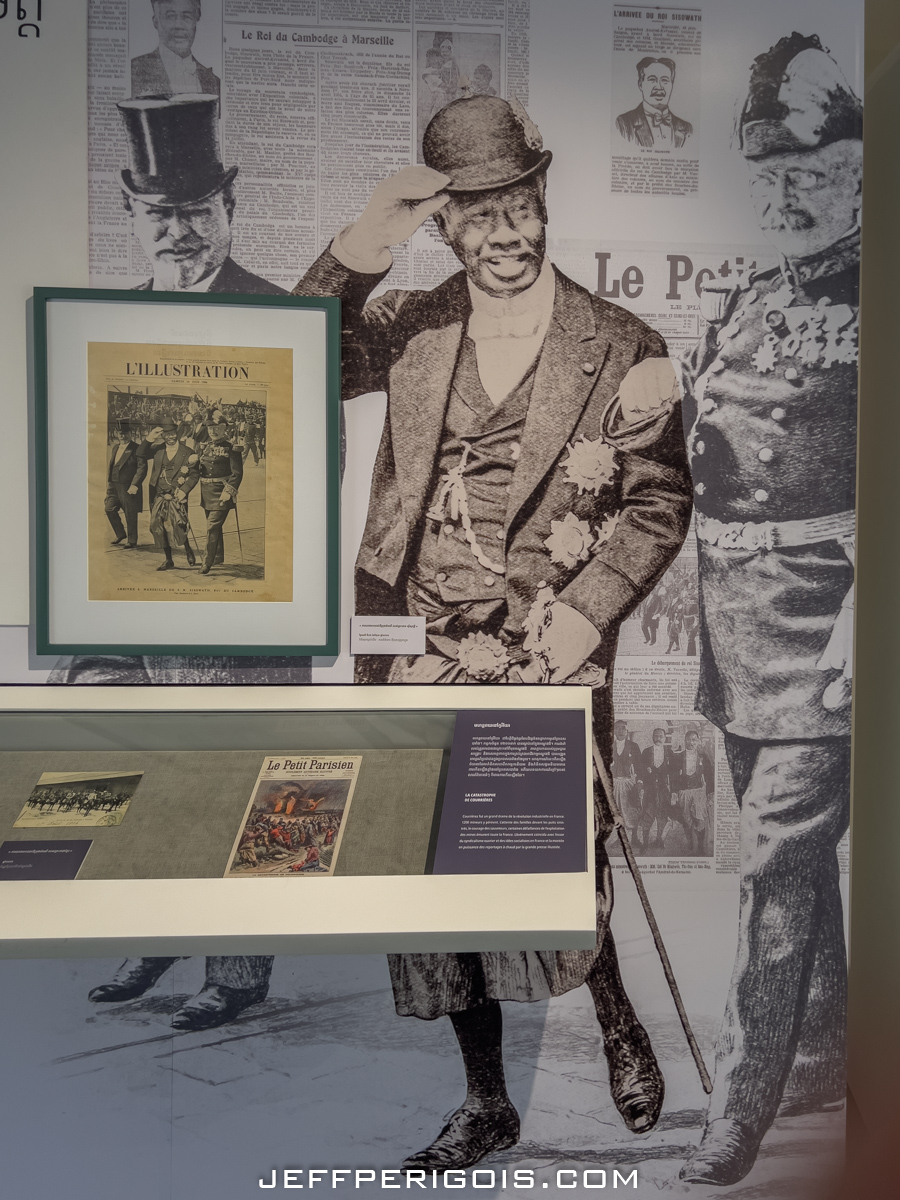

Exhibition on King Sisowath’s triumphal visit to France in 1906. Photo: Jeff Perigois

Exhibition on King Sisowath’s triumphal visit to France in 1906. Photo: Jeff Perigois

In addition to this summary of Cambodia’s history over the last 2,000 years or so presented in an way that makes one forget one is actually getting a history lesson, there is a temporary exhibition on King Sisowath’s visit to France that caused a media frenzy in 1906.

The king was welcomed with the enthusiasm that would be reserved for superstars decades later. Before his arrival, the French public had learned that, upon hearing that 1,200 workers had been killed in a mining accident in France, King Sisowath had sent a large donation to the workers’ families. This contributed to the fact that, throughout his stay from June 10 to July 20, 1906, enthusiastic crowds cheered him wherever he went, and the press covered his every move. The dancers of the Royal Ballet who travelled with the king also fascinated the general public as well as painters and artists.

Visitors at the Sosoro Museum watch a video. Photo: Sosoro Museum

Visitors at the Sosoro Museum watch a video. Photo: Sosoro Museum

The Sosoro Museum—whose full name is the Preah Srey Icanavarman Museum of Economy and Money—is a project funded and carried out by the National Bank of Cambodia, Kilian said.

Located on Street 106 near the century-old Central Post Office building in Phnom Penh, it is housed in a French Protectorate building dating from 1908. “It was in a poor state and had to be restored as it is part of the urban heritage,” Kilian said.

The whole museum project, including the building restoration, ended up taking seven years. “This involved huge research work,” Kilian said. Cambodian historians, economists, archeologists and researchers from the Royal University of Fine Arts, the National Museum of Cambodia and other Cambodian institutions as well as international experts from the Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient (EFEO) and other organizations were involved. Among them, Kilian said, was Jean-Daniel Gardere, a National Bank of Cambodia advisor who, among other works, authored the book “Money and sovereignty: an exploration of the economic, political and monetary history of Cambodia.”

Once the information had been compiled, checked and rechecked for historical accuracy, this had to be translated into facts and a story that would be accessible and appeal to visitors of all ages. To better do so, the data was divided into 12 sections on the two floors of the museum with each section featuring an important period of Cambodia’s history, the scenography being done by the Melon Rouge Agency in Phnom Penh.

Museum Co-Director Kilian, who has been in Cambodia since 1999, has worked both in heritage conservation and in business. A French and a Cambodian citizen based in Cambodia since 1999, he worked for several years for UNESCO—he was a member of the permanent secretariat of the international coordinating committees of Angkor and of Preah Vihear—and later served as executive director of the chamber of commerce EuroCham Cambodia.

What first makes the museum unique is the fact that, Kilian said, “it is above all a museum on Cambodia, about Cambodia and that presents facts through the monetary, economic and even commercial lenses.

« The second characteristic of this museum is that it is extremely contemporary, interactive…vibrant with many videos, video reconstitutions based on scientific studies, touchscreens, audio and audiovisual programs as well as games so that visitors can test what they have learned,” he said.

The museum also includes a small store with books and objects relating to the museum and currency.

“But the highlight of the exhibition is a gold coin, a piece that weighs a little less than six grams and is the oldest coin minted by a Khmer king found until now,” Kilian said. “Dating from the 7th century—the Chenla period—it was minted under Isanavarman I.” The particular coin may have served more as a medal than money as such, he said.

The museum is located at 19 Street 106, with the side entrance leading to the special exhibition and the café being on Street 102.

The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 9 am to 6 pm, except on national holidays.

Tickets are 2,000 riels for children and students of all nationalities, 4,000 riels (around $1) for Cambodians and 20,000 riels ($5) for foreigners. There is access for wheelchairs.

Admission is free for special exhibitions such as the one on King Sisowath’s trip to France.