UN Absent as Bribery, Food Insecurity Create Humanitarian Crisis in Red Zones

- Gerald Flynn and Phoung Vantha

- May 18, 2021 11:07 AM

Corruption and bribery are reportedly behind the mismanagement of Cambodia’s red zones that have left thousands at risk of starvation, meanwhile the UN remains absent despite the growing crisis.

PHNOM PENH--Spanning areas home to some 320,000 people at their peak, the red zones—areas with the most stringent restrictions to prevent the spread of COVID-19—have come to epitomize the Cambodian government’s chaotic response to the Feb. 20 community outbreak and have laid bare the fragility and inequality of Cambodian society.

Implemented one month ago, on April 19, the red zones were mostly established in Phnom Penh’s Meanchey, Por Senchey and Toul Kork districts, but with every passing week since their inception, the government has adjusted the zoning boundaries, creating further confusion.

Unable to leave their homes barring a medical emergency, red zone residents remain reliant on food donations distributed by local authorities, local NGOs and the government-run online store that sells groceries from companies that enjoy close links to the government.

Now estimated to house around 120,000 residents, the red zones have steadily shrunk as a military-run vaccination drive swept through these high-risk areas, but in the month that has passed the threat of food insecurity has loomed large and violence against Cambodians accused of sneaking out to acquire food has been well-documented.

The public calls for help from Cambodians in lockdown reflected the urgency of the situation, with Phnom Penh Municipal Hall setting up a Telegram group chat where affected residents could request food donations from the local authorities. Within days, the group had almost 50,000 members begging for assistance.

Days later, on April 30, protests erupted in Sangkat Stung Meanchey II—a red zone—where residents said they were running out of food. While promises of donations were made amid a flurry of accusations from the Cambodian government’s propaganda apparatus that protesters were motivated by politics rather than the threat of starvation.

These protests were followed by a larger crowd of 300 people from Sangkat Stung Meanchey III on May 13 who were demanding equal access to vaccines, to be allowed out to collect wages from the bank and to earn money while in the red zone.

All of these, along with stark reports from both local and international media, have shone an uncomfortably bright light on the government’s mismanagement of the red zones and the COVID-19 response in general.

While pledging to vaccinate all red zone residents by June 2021, the government’s decision to devolve responsibilities for COVID-19 policies to municipal and provincial authorities has seen many Cambodians fall through the cracks.

An Unfolding Humanitarian Crisis

Those like Van Mokannika in Toul Kork District, Phnom Penh, who—along with her husband and two children—have endured the red zones’ restrictions since their inception with little to no support.

The 29-year-old worked at NagaWorld, Phnom Penh’s only licensed casino, before she was suspended from work on April 4.

The gaming giant had also suspended salaries since mid-March 2021 and—despite reporting $102.3 million in net profits for 2020—announced it would be laying off more than 1,300 of its estimated 8,000 employees.

Mokannika’s husband was working as a deliveryman, but he too lost his work when the red zone rules were imposed, leaving the young family with no income and mounting debts. However, her creditors would pause repayments if she could prove her employer had stopped paying her.

“The labor union has worked hard to request this confirmation letter,” she said. “However, the company seems like they don’t care. It’s just a piece of paper to them, but for me, it is really important.”

With no donations arriving from the government, despite promises made by her local authorities, Mokannika’s child grew ill as they could no longer afford the medication she needed.

“I raised both hands asking money from my friends and some were able to give $1 or $2 to buy medication for my child,” she said, but then came the problem of rent.

The landlord of the room Mokannika’s family rented told her there were no exceptions when it came to late payments as the government had no delayed bank repayments or utility bills.

So far, Mokannika has gotten by on the charity of the NagaWorld union, but she said this month she has had to beg her landlord to let her pay late as there is simply not enough money for the rent, water and electricity bills.

One small comfort that those in the red zones were told they could expect was access to COVID-19 vaccines, which are being administered by the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces in conjunction with commune and village chiefs.

But Mokannika said that she has registered her name twice already and still hasn’t been able to receive a vaccine.

“On April 17, [the village chief] collected names to register for vaccinations and food donations. We registered, but it has been silent since,” she said.

She called on the government to pay more attention to her village as she hasn’t received any donations or vaccination to date.

Bribery Rife as Vaccines and Donations Not Accessible to All

Of the eight red zone residents Cambodianess spoke with, all confirmed that their village chiefs were responsible for issuing vaccination slips and that these pieces of paper are to be taken to the vaccination center where, upon presenting it, residents can receive their COVID-19 vaccine.

However, the residents noted that the vaccination slip was very easy to forge and many of them had seen or heard of people making copies to sell on to other residents who had not been registered by their community leaders.

The registration process, the residents explained, was flawed as it often missed those living in rented accommodation and was ultimately down to the relationship of a resident with their village or commune chiefs and their landlords.

While none of the residents who spoke to Cambodianess said they had paid bribes to acquire vaccination slips, they were aware of these things happening within the red zones.

This came after two women were arrested on May 10 selling fake COVID-19 vaccination cards: proof of having been vaccinated. According to San Sokseiha, a spokesperson for the Phnom Penh Municipal Police, the two women were selling the cards in Por Senchey District, Phnom Penh, asking for 10,000 riel—roughly $2.50—per card.

“We haven’t had an update from the court yet,” he said, adding that the two women were garment workers found in possession of at least 20 fake vaccination cards.

While the government has bet big on vaccinations being the key to ending what has become a public relations nightmare in the red zones, concerns have emerged over the rush to get the population vaccinated, with most residents receiving their second dose just 14 days after their first.

For the Chinese-made vaccines that currently make up the vast majority of Cambodia’s vaccine supply, Dr. Li Ailan—the World Health Organization’s (WHO) representative in Cambodia—said that an interval of between three and four weeks was recommended.

“If the second dose is administered less than three weeks after the first, the dose does not need to be repeated. If administration of the second dose is delayed beyond four weeks, it should be given at the earliest possible opportunity,” Dr. Li wrote in an email. “It is recommended that all vaccinated individuals receive two doses.”

On the overcrowding at both COVID-19 testing centers and vaccine centers in the red zones, Dr. Li said she was aware of issues and that it is important for both local implementers and the public to strictly follow social distancing measures.

“We fully understand that many people want to get vaccinated as quickly as possible, but it is vital to wait for your turn to come and follow instructions. I understand that the ‘crowd’ situation has been significantly improved,” she wrote.

As of May 17, the Ministry of Health said that 2,100,151 people in Cambodia have received their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, while 1,232,928 have received their second dose, which Dr. Li praised as an “amazing achievement.”

Unequal Access to Donations has Bred Desperation

The overall lack of effective management in the red zones has left many questioning whether corruption is guiding the food donations meant for Cambodia’s most vulnerable.

Kang Dara Reach, a resident in Sangkat Stung Meanchey I who has been in lockdown since April 15, said that he has no work, no food and no money for rent or baby formula for his 5-month-old child.

“I ask for charitable people to help me with the baby food, that’s the real concern for me,” he said. “My wife and I are satisfied if our baby has enough food.”

Donations from the government have been sporadic and unevenly distributed, he said.

“As I have observed, some areas were given many donations while some didn’t receive even one,” said Dara Reach.

“We didn’t receive our first food donation until May 6, but other neighbors have already had several donations compared to our one, it’s been a huge stress,” he added.

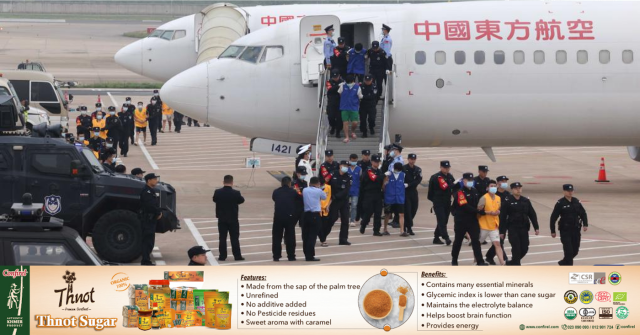

Others trapped in the red zones have been pushed beyond the limits of the law. While authorities intercepted and detained 104 people attempting to sneak out of the red zones in order to return to work on May 8, many other, more subtle escapes have been successful as desperation has pushed people to go scavenging for food, despite the COVID-19 risks and restrictions.

“We only got one donation from the government and that was back on April 30,” explained Tem Sakhena, a garment worker in Por Senchey District. “We’ve run out of food repeatedly, so my husband has had to sneak out a few times, but even then, the food is expensive and he can only come back with enough food for one or two days.”

Sakhena said she has been sharing the fruits of her husband’s foraging missions with neighbors, all of whom are in the same situation as her.

Also grappling with debt and negotiating late rent payments, Sakhena said that life in lockdown has become unbearable as she can’t afford to stay here, but cannot travel back to her hometown.

“People are facing such a severe deterioration as food supplies and money have run out, people are desperate—if we could return to our hometown, I think it would actually lower the risk of COVID-19,” she said, adding that she heard other villages were receiving much more donations from the government.

No Access to the Red Zones for the UN

Even as events portrayed the growing need for urgent assistance in the red zones, sources familiar with the situation noted that Pauline Tamesis—the UN Resident Coordinator in Cambodia—only formally requested UN agencies be given access to the red zones on May 4, some three weeks after 50,000 Cambodians requested support from Phnom Penh City Hall.

According to the same sources, City Hall is yet to allow Tamesis and the UN to directly provide assistance to residents in the red zones, saying that support could be provided from the UN to the government, who would then distribute it themselves.

When asked why the UN had not formally sought the government’s permission to enter the red zones and provide much-needed humanitarian assistance, Tamesis initially declined to answer, referring reporters to a UN note documenting their role in the COVID-19 response.

“The United Nations has been supporting and continues to assist the Royal Government of Cambodia in the COVID-19 response and recovery, since the start of the pandemic,” Tamesis wrote in an email, adding that the UN’s focus had been on mitigating health and socio-economic impacts of the pandemic on Cambodia’s most vulnerable.

She again declined to say what had caused the delays in UN activity, instead noting that the WHO is assisting as technical lead in terms of the health response and had been deployed to red zones along with the Ministry of Health.

“On food assistance, the Humanitarian Response Forum (HRF) partners are coordinating directly with local authorities,” she wrote. “The assistance is intended to complement ongoing efforts of the government.”

However, a rapid assessment of the deteriorating situation in lockdown was conducted by the Humanitarian Response Forum—a collection of UN agencies and international NGOs—from April 26 to May 1. According to the as-of-yet unpublished report, 61 percent of the 193 respondents lived in red zones and were found to be significantly more affected by the COVID-19 restrictions.

“Whilst 77 percent of respondents stated that they are struggling to access food, only 46 percent have received aid assistance,” the report found. “Over the past seven days, 76 percent of respondents stated that they did not have enough food in their house to meet their families’ needs on one or more occasions.”

It also noted that 93 percent of respondents were turning to neighbors, friends and family when they ran out, while 44 percent were buying food on credit, 37 percent were limiting their portion sizes and 36 percent were restricting food consumption among adults to allow small children to eat.

However, 39 percent reported they were reducing the number of meals eaten each day and 9 percent said they had gone entire days without eating.

“It’s become quite clear that the UN Country Team (UNCT), as a collective of all UN agencies present in Cambodia, were totally asleep at the switch when this COVID-19 wave hit and the Cambodian government rushed out its draconian, rights abusing, and totally ill-prepared ‘red zone’ strategy,” said Phil Robertson, deputy-director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia Division.

He pointed out that people in red zones have been facing an emergency food crisis for over a month, since lockdown restrictions began, adding that he was disappointed by the UN’s response to the crisis.

“Not only did it take weeks for the UNCT to finally act, but the UN’s humanitarian requests seem to be half-hearted and all too willing to take ‘no’ for an answer from the government. Even when the Phnom Penh Governor refused the UN and aid groups’ access to red zones, there’s not been a peep of public dismay from the UNCT,” Robertson said.

Problems will Persist Beyond the Lifting of the Red Zones

While the UN’s absence from the red zones has been apparent to those working in the development sector, there has been an emergence of local, informal charities and donation mechanisms that have worked tirelessly to plug gaps left by the government and its partners.

Small networks of charitable individuals have been putting their skills to use in addressing the humanitarian crisis for the past month, including Local4Local, which enlisted out of work cyclo drivers to help deliver free food. COVD Help has also managed to distribute large volumes of food to those within the red zones by teaming up with the Independent Democratic Association of Informal Economy. Art4Food has also seen Cambodia-based photographer selling prints in order to raise money to support the most affected by COVID-19.

But the generosity of these local networks, while vital, is unlikely to be able to address the sheer scale of the problem in Cambodia’s red zones.

“There is still a dire need for food, cash, medicines and basic necessities in red zones in the capital, some of which have been locked down for more than a month,” warned Naly Pilorge, director of local rights group LICADHO. “People who are publicly pleading for food or medicines are not trying to score political points, they’re trying to survive.”

On April 19, there were 49,827 households in red zones, but this has grown smaller as more zones have been downgraded to orange or yellow zones. According to Phnom Penh’s Deputy Governor Koeut Chhe, the red zones will be reduced further on May 19.

For Pilorge, the Humanitarian Response Forum’s findings were not only “deeply troubling” but they suggest that urgent support and assistance will be needed even if the red zones are lifted.

“The government has not yet delivered food to everyone in need and at risk of hunger, while also not officially letting civil society groups and UN agencies to help many of the most vulnerable,” she added. “We urge the UN and other government partners to push harder for access to these areas, and call on the government to lift restrictions on groups that are capable of delivering emergency aid in a safe manner.”

All the while that politics are playing out over who will fulfil what role in Cambodia’s COVID-19 response, it is—as is so often the case—ordinary people who will suffer until an effective means of cooperation is found.

“The food donations just aren’t enough, the only nutrition I’ve got is from noodles and canned fish, but that’s running out too as I live with two family members,” said Va Mach, a garment worker in Por Senchey District.

Having been denied a suspension on her debt repayments, Mach said she has no money for this month and cannot return to work as, like many in the red zone, she has registered repeatedly for a vaccine that she has not yet received.

“I really need money, I can’t pay my debt and food prices are increasing everywhere,” she said. “Please, I call on the government, the food donations aren’t enough.”