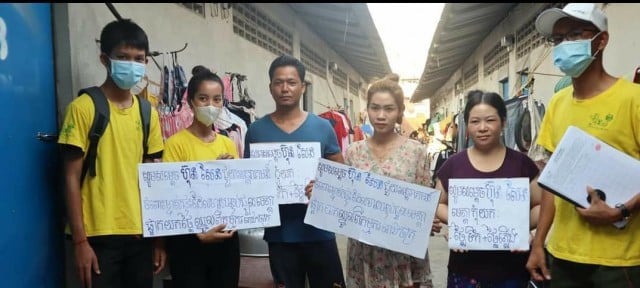

Union Leaders Urge Government to Protect Informal Workers

- By Lay Sopheavotey

- and Teng Yalirozy

- December 14, 2021 1:26 PM

Denied access to social services and often unheard and unrecognized by the government, informal workers make up a huge bulk of the Cambodian workforce and unions want more rights for the sector

PHNOM PENH--Informal workers have the same rights as formal workers and should be provided the same legal protection, union leaders have said, calling on the government to do more to recognize the formation of community groups and unions among informal workers.

Vorn Pov, president of the Independent Democracy of Informal Economy Association (IDEA), said in Cambodia, informal workers are scattered, splintered and not widely recognized by the authorities or professional institutions.

This is despite the sheer volume of informal workers in Cambodia. The International Labor Organization in 2018 estimated that some 93 percent of work in Cambodia was informal, yet IDEA—which has some 14,000 members—argued that little has been done by the government to protect the rights of informal workers.

“Creating these communities will raise the voices of informal workers and encourage the government to respond to their needs regarding social protection as well as other conditions,” he said.

Uniting the informal workers is an essential first step in organizing the strength and voice to effectively address their challenges, Pov said. The right to bind as a group is exercised in accordance with the law, but informal workers are still not protected under existing legal and regulatory frameworks.

Ou Tep Phallin, president of the Cambodian Food and Service Workers Federation, explained that informal workers nowadays have no representatives in discussions with lawmakers or policymakers. As such, informal workers have no-one to compile the issues they face and submit them to the government.

Issues such as access to the National Social Security Fund, the ID Poor program along with healthcare and other benefits afforded to formalized workers are all on the agenda, but the range of informal work undertaken has resulted in many competing issues and voices.

“The representatives should not raise only issues but also solutions,” she said. “We should not only talk about the problems. Thus, the role of union, community, and association is to strengthen the right and power of informal workers while they have to agree on the specific issues and propose to the government for assistance.”

The representatives of informal workers are crucial as they will disseminate information from the government and civil society organizations to informal workers in each sector said Phallin. However, she acknowledged that the unification process will be fraught with obstacles, such as a lack of support and persecution.

“Obviously, complicated problems will occur because the officials are not fully cooperating and fully supportive, especially in setting many conditions, and the number of people who know how to lead the whole informal economy is still limited,” she said.

At the same time, she is also concerned about the establishment of various legal mechanisms that do not empower workers but instead increase abusive conditions.

“The registration [of organizations] is difficult and can only be done by word of government officials. They sometimes require conditions that are beyond the law,” Phallin said.

Heng Sour, a spokesman for the Ministry of Labor and Vocational Training, said that he was unaware of the issues facing informal workers.

“We do not know what the problem is because they do not raise the obvious issues,” he said. “If there is a problem, please mention it.”

Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within borders, according to Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which Cambodia respects and recognizes. At the same time, the Constitution of Cambodia also states in Article 36 that all citizens have the right to social security, insurance, social benefits, and the right to join a union.

Cambodia has many important conventions with the International Labor Organization, including the Convention on the Freedom of Association and the Protection of the Right to Organize, the Convention on the Right to Organize and Negotiate Collective Agreements, and the Convention on Occupational and Employment Discrimination.

However, these rights have been eroded over the years by the Law on Associations and Non-governmental Organizations and the Law on Trade Unions, both of which have further restricted the rights of workers and communities to organize and be formally recognized.

Pov and Phallin echo each other’s concerns, saying that the rule of law sets out the rights of informal workers, so they should be as protected as formal workers. The government’s policies should be in line with the law so that their rights will be restored as they will be free, protected, and not discriminated against.

Pov stated that empowering and supporting more informal workers groups would be the most beneficial thing for the government to do because helping the informal workers access basic social services can be tantamount to lifting them out of poverty and removing key vulnerabilities.

A 2019 report from Oxfam suggested that some 1.6 million Cambodians work as street hawkers, while an untold number—estimated at some 40,000 by researchers—work as edjai or scrap collectors. Tuk-tuk drivers and taxi drivers are thought to number more than 20,000, but the rise of ride-hailing delivery apps means there are likely more informal delivery workers who the apps often render self-employed.

“When they unite, their understanding will be expanded,” he said. “If the government supports and protects them, Cambodia will receive more benefits.”