A Photo Exhibition Starring Cambodia’s Scenery over Years Shows Landscapes at Times Altered

- By Michelle Vachon

- December 14, 2023 10:50 AM

PHNOM PENH — The photos exhibited at the French Institute’s gallery as part of the Photo Phnom Penh festival were taken during a project that took photographer Kim Hak more than 10 years to complete.

And like most of his work, the photos in this series he named “My Beloved” were taken to show and also record the present in Cambodia—his beloved country—for tomorrow’s archives.

“The idea of [this series] came from the fact that, when I travel outside Cambodia, people know the country by two mentions,” Hak said. “It’s always cliches: Angkor Wat and the Khmer Rouge…I wanted to respond to this and say that Cambodia is more than [that]. So in 2012, I decided to travel slowly around Cambodia to photograph the diversity of the landscape in the country. I travelled from the north to the south, more or less following the [Mekong] river, and around Cambodia to photograph the country.”

But over time, what Hak had photographed progressively went from being today’s images to archive as development altered the landscape. “Firstly, I photographed as positive image [of the country],” Hak said. “And after like five years, I looked back and realized that some landscape had changed and disappeared. So, this [shooting] became like positive and also critic.”

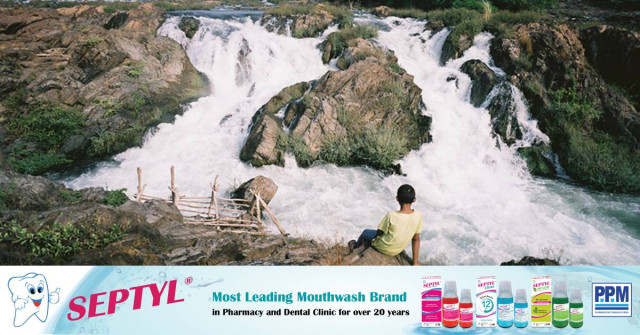

Photos include a peaceful scene of a boy watching the Sopheakmit waterfall near the country’s border with Laos in Preah Vihear province in 2015, and small wooden buildings with metal roofs and large jars in front, which is a gravesite of indigenous people in Mondulkiri province also photographed in 2015, to a 2020 photo of Boeung Kak lake viewed from a construction metal fence and showing an expanse of dirt ground with some weeds leading to a section of the lake as highrises can be seen in the distance.

Born in May 1981, Hak is originally from Battambang province. After obtaining a bachelor degree in tourism at the National Institute of Management in Phnom Penh, he worked for the APSARA National Authority, which manages the Angkor Archeological Park, for two years, and for a travel agency in Phnom Penh for five years. Then, he said, “I jumped into photography.”

In 2009, he studied photography in Malaysia. That same year, he was selected to take part in the workshop of the Angkor Photo Festival in Siem Reap province, which was given by a professional foreign photographer and involved a small number of selected participants. “It was a very tough workshop,” he recalled.

In 2010, Hak studied in the Studio Image program, an 80-hour intensive training offered by the French Institute in Phnom Penh. In the following years, he took part in workshops in Cambodia, Singapore and Thailand.

People in 2020 board the Arey Ksat Ferry as Phnom Penh appears in the distance. Photo: Kim Hak

In the meantime, he started working on photo projects.

Following the death of King Norodom Sihanouk in October 2012, Hak documented Cambodians’ response to his passing and the king’s funerals, which was published in a book entitled “Unity,” which was released as a limited edition. At the photographer’s website, the book is described as “first and foremost, the coming together of an entire country, Cambodia, whose people are united by deep sorrow.”

By then, Hak had already embarked on a project still ongoing that could be described as visual anthropology as he does at his website. Since the early 2010s, he has photographed objects that Cambodians hid right before or during the Khmer Rouge regime of 1975-1979, at times taking risks to do so that could have cost them their lives if found out. This might be family mementoes, photos, or objects from their lives prior to the regime or objects having belonged to those who did not survive. They also might be identity cards or diplomas people had put in plastic bags and buried to hide the fact that they were educated or government officials which, if found out, could have had them killed.

As stated at Hak’s website, “[w]ar can kill victims, but it cannot kill the memories of the survivors. The memories should continue to be alive, known and shared in the current consciousness of human beings, and the preservation of heritage for the next generations.”

Chapter 1 of this project involved people from Battambang province and was completed in 2014. For Chapter 2, Hak interviewed Cambodian refugees now living in Brisbane in Australia in 2015; for Chapter 3, Cambodian refugees in Auckland, New Zealand, in 2018; and for Chapter 4, Cambodian refugees in Tokyo, Kanagawa and Saitama in Japan in 2020.

Hak intends to next interview Cambodian refugees who have been living in Canada, the United States and European countries with the idea of later publishing all the photos in a book.

In 2011, Hak was awarded the 2nd Prize at the Stream Photo Asia international festival in Bangkok. At the Xishuangbanna International Photo festival in China, he obtained the Outstanding Photography Award in 2018 and the Best Foreign Photographer Award in 2021.

In addition to Cambodia, Kim Hak’s work has been exhibited in Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hong Kong, Japan, Nepal, New Zealand, Slovakia, Thailand and the United States.

Although his photos exhibited at the French Institute are meant to show the present, the scenery featured in some photos may since have been altered.

The exhibition includes the “tools of the trade” that Hak used to shoot this series such as the motorcycle on which he crisscrossed the country and his camera and film.

Because he has been using film rather than taking images digitally. Hak’s concept for the series was, he said, “what to say in a love letter to the country. So, I decided to put that on film and used a medium format camera to photograph…I wanted to slow down at each place, to observe and to, like, breathe and feel the place,” he said. “And when using film, the process takes longer, you need to slow down.” Because working with a limited number of possible shots on film makes one think carefully about each one, he said.

The downside of this is that, while film was still sold and could be developed in Phnom Penh when Hak embarked on this project a decade or so ago, this is no longer the case. He must now go to Bangkok to have his film developed, and even in the Thai capital, the number of places where film can be developed has dropped, he said. “I had to change lab like three times…in Bangkok to develop that film,” he said, due to labs shutting down.

Getting film is also not that simple, Hak said. He has been able to purchase film in Singapore and in Japan whenever he travelled to those countries. “Also, I ask my friends to send me film from the U.S.,” he said.

Kim Hak’s exhibition entitled “My Beloved” at the French Institute runs through Jan. 27, 2024.

For information on the exhibition at the French Institute:

https://institutfrancais-cambodge.com/photo-phnom-penh-2023/#/

For information on Photo Phnom Penh:

https://www.photophnompenh.com/

and https://www.facebook.com/PhotoPhnomPenhAssociation/

Gravesite of minority people in Mondulkiri province in 2015. Photo: Kim Hak