Cambodia’s Independence: What It Took to Make This Happen 70th Years Ago

- By Michelle Vachon

- November 9, 2023 8:45 AM

PHNOM PENH — When King Norodom Sihanouk declared Cambodia’s independence on Nov. 9, 1953, this was the result of forcing France’s hand.

Ahead of his time, the country’s leader had mainly done so through the international media, a master at waging political battles in the press as he would do in the years to come.

Because at their meeting in Paris in March 1953, French President Vincent Auriol had refused to even consider granting the country its independence. So, King Sihanouk in April 1953 had embarked on an international media tour in Canada, United States and Japan to build support for his cause.

Then when the 30-year-old king returned to Cambodia, he took a series of measures he would later describe as the “Cruisade for Independence” to force France’s hand.

By August 1953, France, which was at war with the nationalists in Vietnam and was not eager to trigger a conflict with Cambodia, agreed to open negotiations.

King Sihanouk would proclaim independence on Nov. 9, 1953. The end of France’s control over Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam would become official in July 1954 with the signing of the Geneva Accords.

This concluded 90 years of French administration in Cambodia that had started with King Ang Duong writing to France in 1853 and asking for protection against its powerful neighbors, Vietnam and Siam (today’s Thailand) that kept seizing its territory.

France ‘s Protectorate: an Agreement whose Time Had Come and Gone

In the early 1950s, the idea of ending the French Protectorate had been circulating for several decades among some Cambodians in the country.

While there had been some protests and incidents against the French administration—usually triggered by tax collection—the first movement for independence was born with the first Khmer-language newspaper in the country. The Nagara Vatta was published in 1936 by Pach Chhoeun and Sim Var, who were soon joined by Son Ngoc Thanh. They were in close contact with the Buddhist Institute and “modernist” monks such as Hem Chieu who were at odds with the traditionalists of the Buddhist sangha, that is, the religious leadership. They were also close to the Lycee Sisowath high school’s student association and the students and teachers of the Advanced School of Pali.

As the concept of self-rule for Cambodia along with other new ideas were starting to circulate among the country’s intellectuals, World War II began in Europe, and Cambodia fell under France’s Vichy regime that sided with Nazi Germany and its ally Japan.

When French administrators heard that Buddhist monk Hem Chieu and his group were planning to take up arms against the French—which was false as he opposed violence—they arrested him on July 20, 1942, and immediately disrobed so that he could be tried as an ordinary civilian, historian Henri Locard writes.

“A peaceful demonstration of more than 500 monks and 500 lay people was held on July 20, 1942, to ask for his release,” he writes. “The French authorities responded by arresting Pach Chhoeun who came to meet them and submit the request…The incident was followed by severe measures to curb the movement and any progressive ideas in politics or religious institutions. The Nagara Vatta was shut down.”

Tried in front of a French military tribunal, Hem Chieu and Pach Chhoeun were accused of making anti-French remarks, regretting the loss of the western provinces—Battambang province and parts of Siem Reap, Kompong and Stung Treng provinces had been given to Thailand at the start of the war—and planning an armed rebellion, Locard writes. Condemned to death, their sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Hem Chieu died in the French penal colony of Poulo Condor in Vietnam and Pach Chhoeun was released at the end of World War II.

Although still in their early stages, plans to obtain Cambodia’s independence were being discussed by a group of men with a prince as its leader, Locard writes. “If we read certain declarations of Hem Chieu, it is clearly King Sisowath Monivong’s eldest son, Prince Sisowath Monireth, who was banished from Phnom Penh after the 20th July 1942 demonstration. The French administration sent him to join a French assault army division fighting in North Vietnam, Locard writes. “His crime? To have chatted with Pach Chhoeun in front of his house [on Norodom Boulevard]…when the demonstrators were marching.”

Cambodia’s First Elections and Parliament

In March 1945, as its ally Germany was losing the war in Europe, Japan had seized power in Indochina, and taken all French people prisoners. General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, who had won series of battles against the German forces in Africa and Europe during the war, was sent to regain control of Indochina.

As he was doing so, he approved the draft of an agreement with Ho Chi Minh, president of Vietnam that was being recognized as a free state in the French union. Leclerc saw this agreement recommended by French government negotiator Abram Karnow as a diplomatic solution, which was better than risking an armed conflict in the region, said U.S. journalist and historian Stanley Karnow. However, French businessmen, planters, and officials in Vietnam were, Karnow writes, "indignant at the prospect of losing their colonial privileges." Unlike Leclerc, they believed they could go back to life before World War II. So, the agreement was rejected, and this led to decades of war in Vietnam and along the Cambodian border that would affect the whole region.

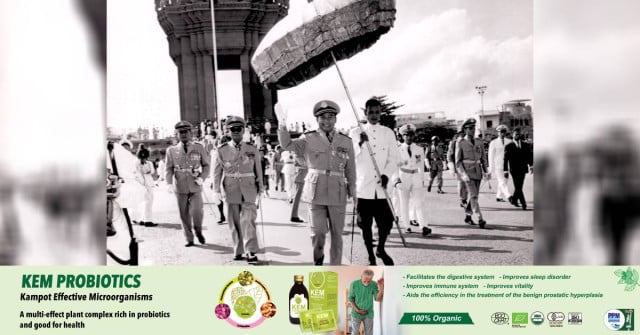

Ceremony at the Independence Monument in Phnom Penh in the 1960s. Photo: ©Queen Mother Library

Ceremony at the Independence Monument in Phnom Penh in the 1960s. Photo: ©Queen Mother Library

In Cambodia, the French soon realized that going back to the pre-war situation would not be possible, historian David Chandler writes. “[T]he French were forced in October 1945 to make conciliatory gestures to the members of the elite whom they needed to run the kingdom’s day-to-day affairs,” he writes. This included putting in place an electoral system for Cambodians to choose their own leaders. “For the first time in their history, Cambodians were allowed to form political parties…(which) opened up deep and unexpected fissures in the Cambodian elite.”

One of the two leading parties was the Democratic Party led by Sisowath Yuthevong who wanted to see in Cambodia the kind of democracy he had seen in France, Chandler writes. “His party’s program called for negotiating Cambodia’s independence as quickly as possible.” The party attracted younger members of the bureaucracy and the country’s young intellectuals, he writes. “[The party also] attracted people who had been drawn in the early 1940s to the “Nagara Vatta” [newspaper].”

The Liberal Party, Chandler writes, “drew its strength from elderly members of the government, wealthy landowners, the Cham ethnic minority and the Sino-Cambodian wealthy landowners. The party was led by Prince Norodom Norindeth. “As one of Cambodia’s largest landowners, he believed that Cambodian politics should involve educating the people—rather slowly—and maintaining a dependent relationship with France.

“In September 1946…elections for the Consultative Assembly were held to form a group to advise the king about a constitution for the country,” Chandler writes. More than 60 percent of the newly enfranchised voters went to the polls. The Democrats won fifty of the sixty-seven seats, the Liberals fourteen, and independent candidates, three.”

But then, events as well as the opposition from the people who held the economic power in the country blocked the measures needed for the country to gain independence. “The Democrats…were in fact powerless to impose their will on the elite,” Chandler writes. “By the end of 1949, all the same, the French appeared to have caved in. A treaty signed at that time granted what [King] Sihanouk was later to call ’50 percent independence.’”

Then a series of events would get in the way of the country gaining its independence, including the death of Prince Yuthevong due to illness in July 1947 and the assassination in January 1950 of the Democratic Party Leader Ieu Koeus by a grenade thrown into the party’s headquarters.

King Norodom Sihanouk Gets into Action

Then King Sihanouk, who was barely in his 30s, got involved. “No single event explains why [King] Sihanouk increasingly involved himself in Cambodia’s political life from early 1949 onwards,” historian Milton Osborne writes. “Several factors played their part. Most importantly he came to realize that the unproductive character of domestic politics, the lack of any real progress on the issue of independence, and the growing insecurity throughout the country [due to the war in Vietnam] posed a danger to his own position.”

This started on June 15, 1952, writes Charles Meyer, a French diplomat who lived in Cambodia from 1946 to 1970 and served as communication and public relation advisor for King Sihanouk. On that day, he writes, “the king discloses his intentions. He dismisses the National Assembly and assumes absolute direct power for three years. The National Assembly does not react and earns a 3-month reprieve.” In January 1953, King Sihanouk would dissolve the National Assembly, put nine Democrat parliamentarians in jail and declare the nation in danger.

The following month, King Sihanouk left for France. His two letters to French President Vincent Auriol, in which he was pleading for the country’s independence, produced no result. So he left for Canada in April 19, 1953, Meyer writes. In United States, he met with Secretary of State Foster Dulles who told him to be patient. But then, “his interview with The New York Times made waves and prompted the opening of the French-Cambodian talks on April 23 [1953],” he writes.

Back in Cambodia, since there was little or no progress in the negotiations, King Sihanouk launched a nationwide call to arms. “This bluff was a stroke of genius,” Meyer writes. “the population responds massively, in a happy and noisy mayhem to this royal call…[maybe as many as] 200,000 people rush to the paramilitary training sessions.” Cambodian military divisions under French command deserted to join the volunteers.

While this did not constitute a true military force, King Sihanouk’s “Royal Crusade” worked politically. On July 3, 1953, the French government announced being ready to open the negotiations for the independence of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. “King Norodom Sihanouk returned on Oct. 29 in triumph in his capital to preside over the solemn ceremony of independence restored,” Meyer writes. He would proclaim the country’s independence on Nov. 9, 1953…[His] indisputable credit had been to combine diplomatic and political means while avoiding to shed blood to hurry the advent of an independence that France was going to be forced to grant to his country.”

One of the outcomes of the events that led to independence was that, Milton Osborne writes, “[King] Sihanouk now dominated the political scene. Whatever problems remained to be solved, the king could confront them with a combination of personal assets that nobody else could match.” It would be more than a year before King Sihanouk would step down from the throne on March 3, 1954, and after the coronation of his father King Norodom Suramarit, found his political party, the Sangkum Reastr Niyum, whose name would become an era in the country.

While a great deal needed done in Cambodia, starting with setting up a school system nationwide, the country would also be affected by the war in Vietnam. But Cambodia was facing this as an independent nation that soon became part of international bodies such as the United Nations that the country joined in December 1955.

As for the country’s relations with France, they remain cordial. By 1964, there were 6.000 French people in Cambodia, that is, two times more than prior to independence, and in 1966, Prince Sihanouk would welcome French President Charles de Gaulle with pomp and circumstance.

And Cambodia as a kingdom and sovereign state celebrates this year the 70th anniversary of its independence.