Eco-Tourism Offers Break from Ethnic Poverty

- By Rachna Tim

- February 27, 2023 4:36 PM

KRATIE — Koy, 14, sits at the bow of a tourist boat as it cruises on the Mekong river around his hometown of Koh Samseb, a community-based ecotourism site in Kratie province of northeastern Cambodia.

As the river currents slow down, glimpses of white sand beaches emerge, signaling the delayed start of the tourist season.

With his small stature and sunburned hair flowing in the wind, the ethnic Bunong teenager is often mistaken as being younger than he is.

Most mornings, he helps with the fishing boats when they take products to the local market, but on days when there are tourists, Koy hops on board as a tour guide.

Koy sits at the head of a boat leading tourists cruising the islands.

Koy sits at the head of a boat leading tourists cruising the islands.

On a good day, he can earn up to 20,000 riels (about five US dollars), a fortune to the village children whom he often treats with energy drinks and sodas.

While Koy's enthusiasm for his work is evident, what's notably missing from his life is a consistent school schedule. When asked why he doesn't go to school, Koy shrugs it off.

“Sometimes during the year, I go to school, and sometimes I don't. I like working like this more,” he says.

Changes spell trouble

Koy is not the only child missing school in Koh Samseb. Even with all its environmental potential, the community’s development and infrastructure is still playing catch-up.

The nearest high school is more than 40 kilometers away with no public transport. As most families are still mired in poverty, commuting to school is a luxury most children cannot afford.

“There are very few kids who make it past secondary school in this village, probably even less than two percent,” said Khut Sam Ol, 37, the community leader of Koh Samseb’s ecotourism business.

For many years, Koh Samseb and nearby areas have been home to many indigenous communities, including more than a hundred Bunong and Kuy families. Like many communities along the Mekong, their lives revolve around the river from dawn to dusk.

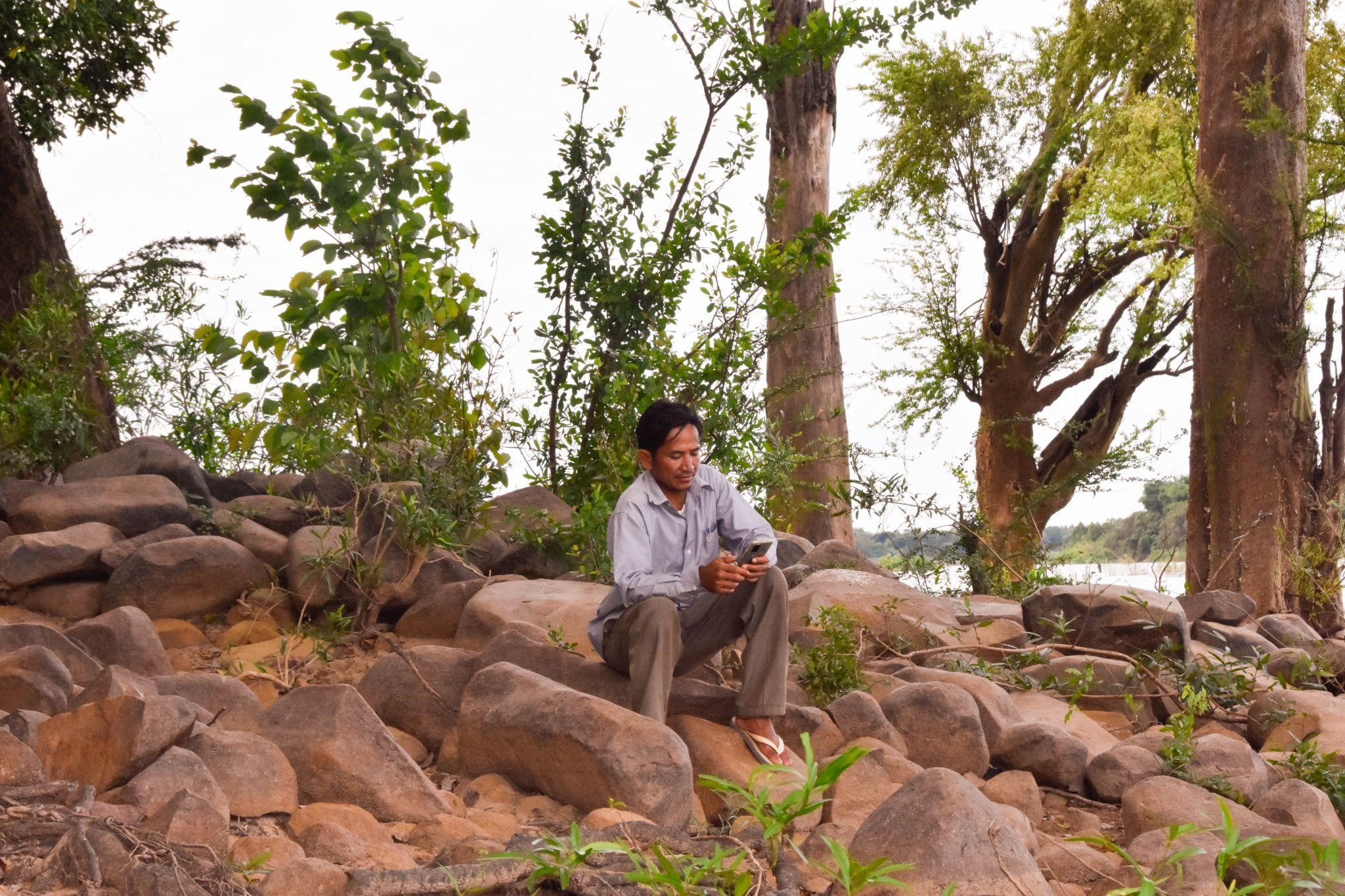

Sam Ol waiting for tourists at one of the visiting spots in the boat tour.

Sam Ol waiting for tourists at one of the visiting spots in the boat tour.

At least 90 percent of the community used to make a living from fishing and many would rely on forest products to further their income.

Indigenous children in Cambodia already face extra hurdles in accessing basic education, which have been exacerbated by school closures and economic challenges brought by the pandemic.

About 200 million out of 800 million people in the Mekong region are classified as poor and remote in which some of the poorest communities are made up of indigenous people.

With climate change, hydropower dams, and illegal logging and fishing, the Mekong has been transformed beyond recognition, and existing vulnerable upland forest-dependent communities are likely to be pushed even deeper into persistent poverty.

“Tens of millions of people rely on the Mekong's natural resources mostly for fisheries and agricultural production and the Mekong's bounty is threatened to be wiped out by upstream dams, poor land use choices, poor regulation of extractive practices like fishing and sand mining, and climate uncertainty,” said Brian Eyler, the director of the Stimson Center Southeast Asia Program, an open-source online platform for near-real time monitoring of dams and environmental impacts in the Mekong Basin.

“Key livelihood practices for people living near the Stung Treng flooded forest are particularly at risk from these impacts. If their fishing bounty is wiped out, their villages will empty out and people there will likely move to larger urbanizing areas looking for jobs. Others will languish in poverty,” he added.

But for the people, it does not leave them much of a choice.

White sandy beach starts to shyly emerge from water, signaling that it is preparation time for the one-season ecotourism.

White sandy beach starts to shyly emerge from water, signaling that it is preparation time for the one-season ecotourism.

Even when fishing is no longer reliable and the rain doesn’t come when expected, it is still the only way of living that most indigenous people have known, having been passed down from generation to generation.

Sam Ol, an ethnic Kuy, is a native of this Mekong community. He used to poach wildlife for a living until he left his hometown in 2004. When he returned in 2008, he decided to turn over a new leaf and put his mind to leading the community ecotourism business to boost the village economy.

He is also a father of two teenage daughters whom he had to pull out of school because commuting was no longer safe.

“When students drop out of school, some of them turn to drugs or illegal activities,” he said. “It is very bad for their future and it causes great harm to the village’s stability.”

Sam Ol has tried more than once to lobby for a high school to be built in their inner village where children would not have to commute so far for basic education.

“I asked as well as formally sent a request to those people in positions. But I have never heard anything back at all,” he said.

Sam Ol noticed that more and more children drop out of school every year. With a background of intergenerational poverty and limited education, he fears that they will fall victim to criminal activities such as illegal logging and fishing.

“They have very limited knowledge, so they tend not to think very far into the future. They are also easy to convince or manipulate,” he said.

Sam Ol prepares the boat for tourist tour cruising around the islands

Sam Ol prepares the boat for tourist tour cruising around the islands

Dreaming big

But Sam Ol is not ready to give up on his native land. He is a believer that if the livelihood of the people can be improved, the children will have better access to quality education and infrastructure. And so, he has dedicated himself to transforming Koh Samseb into an eco-tourism spot.

“The idea is that we can create more jobs for the locals here and we can protect the natural resources too,” Sam Ol said. “Some percentage of the profit will be reserved for community development.”

For almost five years now, Sam Ol has been working tirelessly towards this goal. He has teamed up with non-profit organizations, including USAID Green Prey Lang, to build an eco-tourism business that benefits both the community and the environment.

The potential of Koh Samseb as an ecotourism destination is hard to ignore. The village is located in the prime spot of Sambo Wildlife Sanctuary, which is a paradise for river birds with more than 218 documented species, including 50 wetland species and many endangered birds. The area is also blessed with a wide water basin adorned with white sandy beaches, uninhabited by people.

But the journey towards this transformation has not been smooth sailing. Sam Ol and his team have faced resistance from many indigenous people who are skeptical about eco-tourism, preferring instead to stick to their traditional livelihoods of fishing and forest products. Only 16 out of more than 200 families in the village are involved with ecotourism.

A day in life of the people from Koh Samseb in which still revolves around the Mekong River

A day in life of the people from Koh Samseb in which still revolves around the Mekong River

“The most difficult aspect of this job is getting the indigenous people to engage with us. They grow up and live with their own sets of rules and traditions and they don’t want to disrupt that. It is very difficult to change their mindset,” Sam Ol said.

Managing expectations

It was not until newcomers migrated to the community a few years ago that more commercial activities appeared in the village.

Thida, 42, came to Koh Samseb with her husband five years ago to do riverbank farming, leaving her four children with her parents in Kampong Cham province so that they could attend regular schools and have a normal life. Today, Thida is the only woman involved in the community's ecotourism business, taking care of cooking and managing the only homestay accommodation in Koh Samseb.

“I like being in this business of protecting nature too,” Thida said. “If the season is good, I can earn a decent amount of extra income for the family too. However, it is not always like that and it only runs for one season in a year. I cannot totally depend on it yet.”

Inconsistency is a major factor that makes locals hesitant about getting involved in the ecotourism industry. It becomes even more challenging as Koh Samseb must compete with more popular destinations as well as overseas travel as the borders reopen.

“Eco-tourism is not very big in Cambodia yet,” Thida said. “We still have a lot of work to do.”

This means building a pipeline of resourceful people to continue managing and expanding the business. However, this might leave the villagers, who lack basic education, out of the equation.

“Most people here cannot read or write well. It is difficult for them to attend any training or take part in any decision-making. Sometimes they feel inferior because of that,” Thida said.

Thida tells her story of coming to Koh Samseb and how she get involved in the ecotourism as a non-ethnic member.

Thida tells her story of coming to Koh Samseb and how she get involved in the ecotourism as a non-ethnic member.

But Thida and Sam Ol remain hopeful that they can push forward.

“We know that we cannot depend on the Mekong River forever,” Sam Ol said. “The natural resource is not going to be there all the time. We also have to develop man-made potential too.”

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.