King Norodom Sihanouk: Celebrating the 100th Birthday of a Cambodian King Who Defined an Era

- By Michelle Vachon

- October 31, 2022 2:00 PM

When King Sisowath Monivong passed away in April 1941, the French Protectorate officials overseeing Cambodia looked for a successor.

World War II was raging in Europe and the French meant to have a king who would leave it to them to run the country. This eliminated Prince Sisowath Monireth, the son of King Monivong and a prominent member of the Sisowath family who was fighting in France against Nazi Germany.

The French officials soon considered Prince Norodom Sihanouk. Born on Oct. 31, 1922, he was a direct descendant of the two branches of Cambodia’s royal families as his father was Prince Norodom Suramarit and his mother Princess Sisowath Kossamak, which might help unite the two families, the French officials thought. The prince was in Vietnam at the time, attending the Chasseloup-Laubat high school in Saigon. Considered an excellent student, he seemed an ideal candidate to the French.

Little did they know that this shy young man would force France to give Cambodia its independence at the end of a peaceful campaign in 1953, and would become a major political figure in Southeast Asia during the second part of the 20th century.

And this year marks the 100th anniversary of King Norodom Sihanouk’s birth in 1922 and also the 10th anniversary of his death in 2012.

After World War II, France’s determination to continue governing Cochinchina—Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam—as prior to 1939 would soon lead to war in Vietnam and reluctance in Cambodia.

In September 1946, Cambodians voted in the country’s first national elections and elected the Democratic Party whose program included obtaining independence from France. The party also wrote a new constitution: Promulgated in May 1947, it set Cambodia as a constitutional monarchy in which, as King Sihanouk would later say, the king reigned but did not govern.

Due to resistance on the part of France and a series of events, the party failed to implement its program. In January 1953, King Sihanouk assumed power and, launching his “Crusade for Independence” the following month, left for France where he failed to convince French President Vincent Auriol to give Cambodia its independence.

King Sihanouk then embarked on what could be considered a media campaign before its time. He visited Canada, the United States and Japan, granting press interviews during which he would speak of France’s refusal to give the country its independence.

France eventually caved in, and, on Nov. 9, 1953, King Sihanouk proclaimed Cambodia’s independence.

Then in March 1955, King Norodom abdicated in favor of his father who was crowned King Norodom Suramarit as King Sihanouk assumed the title of prince so he could be active in politics.

The same month, Prince Sihanouk launched his political party Sangkum Reastr Niyum. The party would win all the seats in the national elections of September 1955. Shortly after, Cambodia became a member of the United Nations.

The era that would be named after Prince Sihanouk’s party Sangkum Reastr Niyum had begun.

Prince Norodom Sihanouk in June 1964 meets the staff of a maternity ward in Kampong Cham Province. Photo: AFP

Prince Norodom Sihanouk in June 1964 meets the staff of a maternity ward in Kampong Cham Province. Photo: AFP

“The Golden Age of Cambodia has actually been embodied in His Majesty the King Father Norodom Sihanouk because it is him who led the development,” said Prince Sisowath Thomico, a nephew of King Sihanouk and his personal secretary until his death in 2012. “He would be directly involved: development projects, building levees, roads or public buildings, starting, of course, with Independence Monument.”

In sectors such as education, the government had to start from scratch when the country obtained its independence. “In 1953, there was not a single university in Cambodia,” Thomico said. The country’s elite including King Sihanouk had studied first in Saigon and afterwards in France, he said. “Therefore, one of the king’s priorities was setting up schools and universities.”

But first, all those projects, which also included developing the health sector, required people with the knowledge to do so. Which is why scholarship programs were set up to enable promising students to study in France. “[A]ll students who received scholarships to study in France returned to Cambodia: around 90 to 95 percent of them…came back.

“The feeling at the time was wanting to serve the country,” Prince Thomico said. “[And students] had jobs when they would return…in all sectors, whether public or private.”

Economic development took place in all areas whether rubber products ranging from latex to tires as Cambodia had rubber plantations to provide the raw material, or manufacturing and the wood industry that included a paper mill, he said. “We also had Solex factories [bicycles with motors]…We were the first ones [in the region] to have an oil refinery [in Sihanoukville], we were the first ones to have an Olympic stadium [in 1963].”

Medical facilities, schools and universities were built and staffed to provide services throughout the country. All this done by Cambodian teams determined to make the country a modern one—a country whose population at the time was around 6 million, Thomico said, compared to around 17 million today according to World Bank data, while the population of Phnom Penh was 500,000 people compared to around 2 million today.

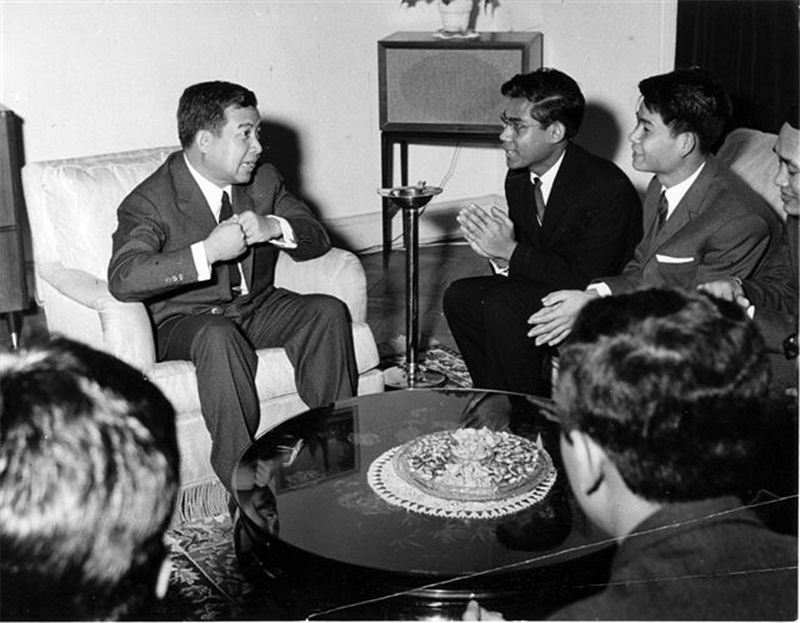

Prince Norodom Sihanouk meets Cambodian students in Paris in the 1960s. Photo: personal archives of Prince Sisowath Thomico.

Prince Norodom Sihanouk meets Cambodian students in Paris in the 1960s. Photo: personal archives of Prince Sisowath Thomico.

King Sihanouk had the genius of picking talented people and letting them do what they did best, Thomico said. “He would define the framework, the objectives and then they had all the latitude to operate.” The country became an autocracy, he said, “to the extent that everything was referred to him but [it was] not a dictatorship.”

Was there corruption in the government? “Prince Sihanouk…gave a speech in 1962 in which he asked the ministers he had appointed to serve the people and not take advantage of them. He said, ‘One cannot fight all corruption. What I’m asking is that two public services not be corrupted: national education and health services.’ So, he knew,” Thomico said. The economic policy would eventually lead to a deficit, maybe due to excessive public-works projects, he said.

With his team handling internal matters, King Sihanouk focused on international affairs, which was of great interest to him and had become a necessity.

As Cambodia was turning into one of the most dynamic countries of the region, Prince Sihanouk had become involved in the Non-Aligned Movement that was meant to promote peace and not take side in the Cold War that opposed the Soviet and the Western blocs. “Prince Sihanouk wanted Cambodia to be neutral: He did not want the country to be drawn into conflicts,” Thomico said. “He had always been proud of the fact that he had obtained Cambodia’s independence without a drop of blood being shed.”

Heads of state take part in the conference of the Non-Aligned Movement in Belgrade in September 1961. Prince Norodom Sihanouk, third from left, stands between Prince Seyful Islam El Hassan, permanent representative of Yemen at the United Nations, left, and Saeb Salam, prime minister of Lebanon. Photo: AFP

Heads of state take part in the conference of the Non-Aligned Movement in Belgrade in September 1961. Prince Norodom Sihanouk, third from left, stands between Prince Seyful Islam El Hassan, permanent representative of Yemen at the United Nations, left, and Saeb Salam, prime minister of Lebanon. Photo: AFP

At the Bandung conference in Indonesia in 1955, participating countries, which included Cambodia, had agreed on the respect of fundamental human rights and the respect of territorial integrity of all countries.

In 1965, Prince Sihanouk supported Singapore’s efforts to obtain its independence from Malaysia, and supported movements for independence in Algeria and Morocco, Thomico said.

The war between the Vietcong and the United States was raging at the time. Backed by China, the Vietcong had set up shelters in Cambodia along the border. In such context, Prince Thomico said, “[o]ne could not differentiate between international, regional and domestic political movements in the country. It was a very difficult situation

“In newspapers in France at the time, Prince Sihanouk would be described as a tightrope walker, trying to do a balancing act between, on one hand, the expansion of communism, and on the other, political relations with the United States and Western countries,” he said.

According to Prince Thomico, the reason why Prince Sihanouk had left the country in 1969 was to meet government leaders to attempt to find a solution and get Cambodia out of the Vietnam war. The country was in a dire economic situation at the time. Asked to return and having declined to do so, Prince Sihanouk was ousted from power in a vote at the National Assembly on March 18, 1970, which was initiated by Prime Minister Lon Nol and Deputy Prime Minister Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak—a vote that Prince Sihanouk and his supporters would call a coup.

After looking into residing in France, Prince Sihanouk accepted China’s invitation to live in Beijing as the head of the Cambodian communist forces supported by North Vietnam: the Khmer Rouge he had combated while in power. In a radio address broadcasted from Beijing in late March 1970, Prince Sihanouk launched an appeal to Cambodians, urging them to take up arms against the Lon Nol regime.

During the following five years, Cambodia would be torn apart by a civil war as the Khmer Rouge backed by the North Vietnamese forces fought for control of the country. At one point, Prince Sirik Matak tried to contact Prince Sihanouk to come up with a solution and end the civil war, Prince Thomico said.

Then in 1973, when a peace agreement was signed between North Vietnam, the United States and South Vietnam, Prince Sihanouk attempted to end the civil war in Cambodia by getting in touch with the Lon Nol government, Thomico said. “For reasons of protocol…it is [Prince Sihanouk’s] cousin Prince Sirik Matak who wrote to Prince Sihanouk the famous letter ‘Dear Cousin’ in which he was actually proposing a peaceful solution…The Khmer Rouge blocked this.”

Following this attempt, Prince Sisowath Methavi, a diplomat who was Prince Sihanouk’s chief of staff at the time, was appointed ambassador to East Germany. After the Khmer Rouge victory of April 1975, Prince Methavi and his wife, who was the sister of Queen Norodom Monineath Sihanouk, were ordered to come back to Cambodia. Sent to the Khmer Rouge camp Boeung Trabek, they were eventually executed. They were Prince Thomico’s parents.

During the Khmer Rouge regime, Prince Sihanouk was brought to Phnom Penh and kept as a prisoner in the royal palace. Shortly before the fall of the regime in January 1979, he was evacuated to China. Throughout the 1980s, he became head of the Cambodian National Resistance, fighting against the Cambodian government that was supported by Vietnam.

Prince Norodom Sihanouk addresses Cambodian refugees at the Thai-Cambodia border in 1982. Photo: Private Collection of Ambassador Julio Jeldres

Prince Norodom Sihanouk addresses Cambodian refugees at the Thai-Cambodia border in 1982. Photo: Private Collection of Ambassador Julio Jeldres

More than a decade later, the Paris Peace Agreements of October 1991 put an end to war and, following Cambodia’s national elections of May 1993 organized by the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), and the promulgation of the constitution, Prince Sihanouk acceded to the throne as constitutional monarch in September 1993.

During the following years, King Sihanouk would discretely attempt to maintain peace in the country and prevent conflicts and rights infringements, often using the media to plead for peace.

Then in 2004, King Sihanouk stepped down from the throne and his son Prince Norodom Sihamoni became king in October 2004.

King Norodom Sihanouk passed away in October 2012.

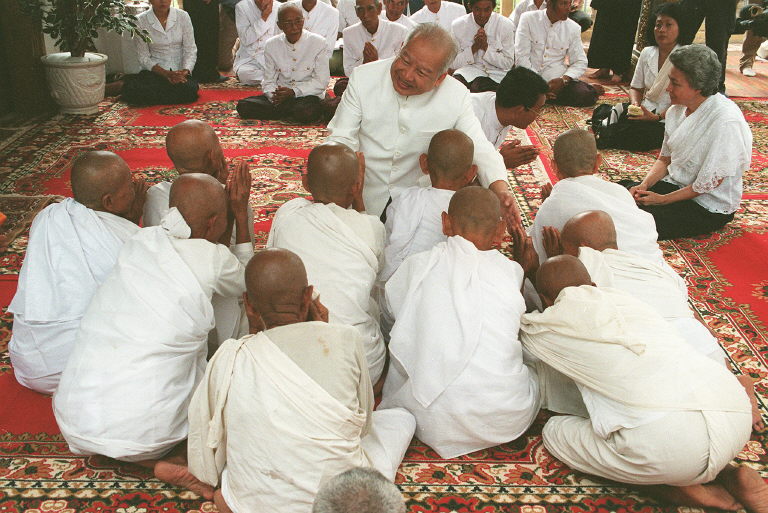

King Norodom Sihanouk is greeted by a group of elderly nuns at a small temple in Siem Reap city on Sept. 1, 1997, with, right, Queen Norodom Monineath. Photo: David Van Der Veen, AFP

King Norodom Sihanouk is greeted by a group of elderly nuns at a small temple in Siem Reap city on Sept. 1, 1997, with, right, Queen Norodom Monineath. Photo: David Van Der Veen, AFP

This year marked the 100th anniversary of King Sihanouk’s birth and the 10th anniversary of his death.

A figure larger than life, he propelled the small nation of Cambodia on the international stage in the 1950s and the 1960s. He remained a prominent figure until his death.

“King Sihanouk would work till late at night, 10 or 11 pm,” Prince Thomico said. “When he was finished, he would watch films in his small theater. Then in the morning, he would get up at 5 am, start working at 6 am and have breakfast while going through files, national and international press clippings. He worked all the time.”

And yet, Prince Thomico said, “[h]is passion was literature…and until his last days, he had a book and would read in bed.” During his last years, King Sihanouk would say that in his next life, he would like to teach literature, he said.

“What I would like people to remember is that King Sihanouk got involved in politics out of obligation,” Thomico said, and his love of Cambodia.