Rising Cambodian Cashew Sector Hindered by Climate Change and Low Processing Capacities

- By Ou Sokmean

- and Meng Seavmey

- February 29, 2024 7:00 PM

KAMPONG THOM – In Cambodia, agriculture is one of the sectors most affected by climate change. Its effects are already seen in many of the country’s crops, including cashew nuts, whose production has soared over the past five years.

Throughout Cambodia’s 470,000 hectares of cashew plantations, climate change has caused abnormal growth of cashew trees, late sprouting, poor-quality flowers, wilted fruits, cracked flesh, black seeds, or damaged and less fleshy nuts.

Being Cambodia’s third largest export product after rice and cassava, the nut has put the country on the map of the globalized cashew industry. In only a few years, Cambodia has become the third largest producer of raw cashew nuts, according to the International Nut and Dried Fruit Council, behind Ivory Coast and India. In 2023, the production reached 658,000 metric tons in the kingdom.

Although farmers, the government, the private sector and development partners are working hard to place Cambodian cashew nuts on international markets, the coming harvest season – which started in February – is likely to be disappointing compared with previous years, because of a particularly strong El Nino effect in the Pacific and rising production costs.

While cashew nuts best grow between 26 to 37 degrees Celsius, “temperatures are expected to reach 38 to 41 degrees in the upcoming dry season because of the warm weather induced by El Nino,” said Chan Yutha, spokesperson for the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology.

Such temperatures make Uon Silot, the president of the Cashew Nut Association of Cambodia (CAC), believes that the country’s cashew production will decrease by 10 to 30 percent this year. He already notes – although without specific data – declines in the early yields in many cashew production areas across the country.

On the ground, Silot’s observations are already confirmed by farmers.

Days too hot, nights too cold

In Kratie province’s Roluos Meanchey commune, Lach Dara has owned a 7-hectare cashew plantation for several years. But since the start of the season, he noticed that cashew flowers have not grown since mid-November 2023.

“In a normal year, I would start harvesting cashews in February. But this year, the cashews haven’t sprouted. There are only one or two cashews in a cluster,” Dara said, adding that in a good year, a single cluster can bear up to ten nuts.

To give nature a booster shot and save his crops, he felt compelled to spray more fertilizer than he had ever done before, even though this came at an ecological and economic cost. “I spread fertilizer at least 10 times already, but with little effect on the crops so far,” he said. “A single container [of fertilizer] costs around $280.”

Climate change has caused Dara’s cashew flowers to sprout only one to three nuts per cluster. Photo: Meng Seavmey

Climate change has caused Dara’s cashew flowers to sprout only one to three nuts per cluster. Photo: Meng Seavmey

After eight years of growing cashews, it is the first time Dara has faced production issues. While he has already spent more than $3,000 in intrants, fuel and workforce to try to maintain his production, he blames climate change and unfavorable meteorological conditions to explain the foreseeing bad harvest.

“The weather has changed since the end of 2023, with days being too hot [for the season] and nights too cold, with dew and strong winds. That’s why my cashews will sprout late.”

“I have never taken loans for cashew plantation. But this year if my production is bad, I may have to get funds from the bank,” he said.

Dara is monitoring the cashew flowers that have not sprouted yet due to climate change. Photo: Meng Seavmey

Dara is monitoring the cashew flowers that have not sprouted yet due to climate change. Photo: Meng Seavmey

National production on the rise

In the same province, Leam Lungheng, owns a 40-hectare plantation in Prasat Sambo district’s Sreung commune. Since last November, the 65-year-old farmer also noted an increase in his production cost, as he too had to spread more fertilizer, hoping to increase his production.

This season, the farmer's $50,000 cash flow comes from the balance of the $100,000 loan he took out when launching his business. Last year, he was able to repay part of this loan thanks to the $20,000 profit he made on his cashew plantation.

But this year, he knows it will be difficult to repay his debt, as he used a large part of the money just to pay for fertilizers and pesticides, while the cashew nuts are struggling to blossom.

But while he hoped to repay the bank with the benefits gained from his cashew harvests, he instead used a substantial part of the money only to pay for fertilizers and pesticides.

Lungheng thinks his cashew production will not be as good as expected this year, and even expects financial losses for the first time since he jumped onto the crop. To make ends meet, he relies on the other agricultural products he grows. “My economy is difficult, but I can earn from my other crops to support myself. If I’d depend only on cashews, it would be over.”

The farmer spends around $25,000 per season on pesticides, fertilizers, and maintenance. An amount that does not include the cost of hiring cashew pickers, who are paid between 500 to 700 riel per kilogram of nuts picked.

Leam Lungheng explained the effects on his cashew plantation caused by climate change. Photo: Meng Seavmey

Leam Lungheng explained the effects on his cashew plantation caused by climate change. Photo: Meng Seavmey

After years of continued growth in the country’s cashew production, the Cambodian government elaborated a National Policy on Cashew Nuts for 2022-2027, which was enacted in 2023. It focuses on increasing the national production of raw cashew nuts, developing the country’s processing capacities, and finding new export markets. The set goals are high: The government seeks to increase the value of the industry by 25 percent in 2027 and 50 percent in 2032. In 2023, cashew nut exports brought $837 million to Cambodia.

But while cashew farmers have to deal with increased production costs, they also see their margin being reduced by lower selling prices on international markets.

Mean Chamroeun, a nut grower from Ou Chum district, Ratanakiri province, said prices have decreased by around 20 percent in 12 months, down from $1.25-$1.37 per kilo last year to $1-$1.2 per kilo today, depending on the nut quality.

“I usually make a profit of $490 to $1,470 per hectare depending on the year. But for this upcoming season, I don’t think I will even make $250 per hectare, given the current situation. Costs have doubled and yields will be divided by half,” said Chamroeun, who is also the vice president of the province’s representation of the CAC.

Chamroeun checked his cashew cuts that are affected by climate change. Photo: Ou Sokmean

Chamroeun checked his cashew cuts that are affected by climate change. Photo: Ou Sokmean

Is organic the solution?

While the very hot and dry start of the year prompted many cashew farmers to rely more on chemical fertilizers and pesticides to try to increase their yields, others have turned to organic farming instead. And they recorded better results.

In Kampong Thom province’s Kampong Svay distrct, Pov Orn has been using manure as fertilizer and leaves – from Chromolaena Odorata, Caramelize Tinospora Crispa, neem, chilly, lemongrass, ginger, galangal, and other trees – as pesticides to get rid of pests for the past four years.

His 5-hectare cashew plantation is 80 percent based on natural fertilizing methods to enrich the soil and preserve its moisture content as climate change has reshaped rain patterns and increased temperatures in the area.

Pov Orn with cashew trees in Kampong Thom province. Photo: Ou Sokmean

Pov Orn with cashew trees in Kampong Thom province. Photo: Ou Sokmean

While cashew trees can be grown on many types of soil, they require constant attention. Being aware of the fragility of the plant, Orn starts spreading fertilizer in July and follows up depending on the soil and crops’ needs.

“Every morning, I also wash the salty dew with [clear] water instead of spraying pesticides on the fruits, unlike other farmers tend do to. Using too much pesticide can spoil the fruits, especially when the weather is hot, like this year,” Orn explained.

The farmer only spreads pesticides three times per season, at the beginning, the middle, and the end of it. He uses pesticides when the flowers sprout, and sprays fertilizer when the cashew pods bear fruits.

He came up with this method after he had a particularly bad crop in 2019. That year, he spent $3,000 on chemical intrants, but only produced one metric ton of cashew nuts.

With his new technique, mostly based on natural products, he’s now able to produce seven metric tons of cashews on the same plantation. “In 2024, I am reducing the use of chemical substances even more because I put some cashew nut shells over every cashew tree root.”

The water tank that Pov Orn used to wear off the salty dew from his cashew crop. Photo: Pov Orn

The water tank that Pov Orn used to wear off the salty dew from his cashew crop. Photo: Pov Orn

Thinking of the next step: Developing processing capacities

To date, Cambodia’s cashew industry is mostly based on cashew nut cultivation but lacks processing capacities, where most of the added value is created. As a result, the vast majority of the country’s production is exported – mostly to Vietnam – for the nuts to be processed. The shell is removed and the ready-to-consume nuts are packaged and sent to the world’s biggest consumers: India, the United States and Germany.

In 2022 and 2023, Vietnam imported respectively 660,000 and 614,191 metric tons of cashew nuts from Cambodia, according to Vietnamese customs and the CAC. Such quantities represent more than 90 percent of Cambodia’s production these two years – 690,000 tons in 2022 and 658,000 tons in 2023.

Being aware that the sector needs funding to keep growing, financial institutions are ramping up, driven by former Prime Minister Hun Sen’s craze for the nut.

“I want Cambodia to become the king of exporting cashew nuts because it is the country producing the most cashew nuts, but unable to process it yet,” he said in a speech in Kampong Thom on March 9, 2023.

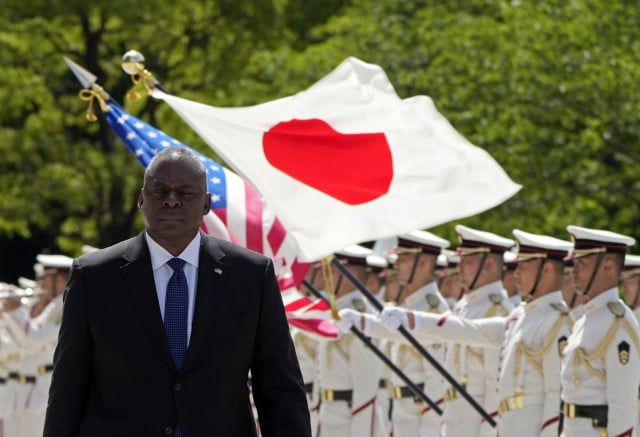

Former Prime Minister Hun Sen. Photo: Former Prime Minister Hun Sen Facebook

Former Prime Minister Hun Sen. Photo: Former Prime Minister Hun Sen Facebook

Over the past two years, the privately owned Angkor Microfinance Kampuchea (AMK), has granted $1 million in loans to farmers in a move to support the development of processing facilities in the country, in association with the CAC.

“AMK’s loan package is $30,000 without securing properties, which is different from the loans for other sectors,” said AMK’s Chief Financial Officer Kea Borann.

AMK’s Chief Financial Officer Kea Borann is also a member of the Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA). Photo: CMA

AMK’s Chief Financial Officer Kea Borann is also a member of the Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA). Photo: CMA

“Every year, Cambodia exports 90 percent of raw cashew nuts, so if we increase processing productivity, local enterprises will need more capital on machines and materials,” Borann added.

CAC President Uon Silot said such loans can make a difference by financially supporting private actors who would be interested in processing Cambodia’s cashew nuts.

Cambodian Cashew Association (CAC) president Uon Silot. Photo: Chhorn Sophat

Cambodian Cashew Association (CAC) president Uon Silot. Photo: Chhorn Sophat

“A few years ago, local [processing] enterprises could only operate for three to eight months as the national production was too low. But since the production increased, such hole in business is reduced,” he said.

As of February 2024, there were 42 small and medium processing cashew nut facilities in Cambodia. Thirty-nine of them can process around 500 tons per year, while the remaining three can deal with 7,000 tons each. Altogether, they can process about 6 percent of the national production.

Anticipating that the upcoming harvest season might not be as good as in the past, some banks and microfinance institutions have also prepared low-interest rate loans for farmers or company owners, to meet their financial needs in the production chain.

Two workers are putting washed raw cashew nuts to dry under the sunlight in Kampong Thom province. Photo: Meng Seavmey

Two workers are putting washed raw cashew nuts to dry under the sunlight in Kampong Thom province. Photo: Meng Seavmey

For CAC’s members, the state-owned Small and Medium Enterprise Bank (SME Bank) provides $100 million in loans with an interest rate of 5.5 percent per year, or 0.41 percent per month. Thus far, around $3 million has been granted to nine different SMEs.

The government also provided $60 million to the Rural Development Bank of Cambodia to support cashew production. Half of the envelope is for cashew farmers, and the other half is for purchasing cashew nuts to incentivize local processing, said Phan Phalla, secretary of state of the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

Phan Phalla, secretary of state of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, at the public forum on the 2024 Macroeconomy Management and Budget Law. Photo: General Department of Budget

Phan Phalla, secretary of state of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, at the public forum on the 2024 Macroeconomy Management and Budget Law. Photo: General Department of Budget

Adaptation to climate change will be key

In Lay Huot, the owner of Chey Sambo Cashew Nut Handicraft in Kampong Thom province, benefited from a similar scheme. She received $500,000 from SME Bank to purchase 15,000 tons of cashew nuts from local farmers in 2024.

This aims to help her purchase cashews locally before farmers felt no choice but to sell them to export markets at a low price. She said on Feb. 11 she helped 100 farmers in Kampong Thom and Preah Vihear provinces, buying nuts for $1.05 to $1.30 per kilogram.

In Lay Huot, owner of Chey Sambo Cashew Nut Handicraft in Kampong Thom Province. Photo: Meng Seavmey

In Lay Huot, owner of Chey Sambo Cashew Nut Handicraft in Kampong Thom Province. Photo: Meng Seavmey

However, to reach the national target of increasing the industry value by 25 percent by 2027, farmers will have to seek new varieties that can be yielded several times a year, said Im Rachna, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

“Experts are working with provincial departments to inspect plantations impacted by El Nino, while also seeking new varieties and more climate-resilient means,” she said.

Rachna added the ministry is working closely with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and other development agencies – including the EU and USAID – to increase the competitiveness of the value chain on international markets.

Im Rachna spoke with reporters during the press tour on cashew production chain in November 2023. Photo: Im Rachna Facebook

Im Rachna spoke with reporters during the press tour on cashew production chain in November 2023. Photo: Im Rachna Facebook

In late 2020, the ADB provided $103 million in loans to Cambodia through the Agricultural Price Chain Competition and Safety Promotion Project to strengthen the food safety and value chain on the processing of six key agricultural products, including cashew crops.

“ADB has assessed the agriculture sector in Cambodia as the most vulnerable to climate change,” said Anthony Gill, ADB’s head of country operations, in an email to Cambodianess on Feb. 14.

ADB’s head of country operations Anthony Gill. Photo: ADB Cambodia

ADB’s head of country operations Anthony Gill. Photo: ADB Cambodia

“Over the last five years, ADB and development partners have financed over $573 million for six projects to help the Cambodian agricultural sector address climate change impacts and build climate resilience,” Anthony added.