The Reclining Vishnu: from a Cambodian Farmer’s Dream to the World Stage

- By Torn Chanritheara

- May 27, 2024 11:55 AM

PHNOM PENH – It was a farmer’s dream that led to the discovery of this masterpiece of Khmer metal casting, the Reclining Vishnu. This was in 1936 at the West Mebon temple in Siem Reap Province. And next year, the statue will be at the center of an exhibition in France.

The Angkorian-era statue, believed to have originally been 6-meter long, will be the centerpiece of a five-part exhibition on Cambodia’s bronze antiquities at the National Museum of Asian Arts-Guimet in Paris. This will take place from April to September 2025, said Pierre Baptiste, curator of the museum’s South-East Asia Collection, during a recent lecture on museum cooperation in Phnom Penh.

The reclining Vishnu will join 126 bronze objects lent by the National Museum of Cambodia for the exhibition, which will provide insights into Khmer bronze casting including the Khmer artisans and artists’ bronze-casting skills, their relation with the royal power, and the religious context of bronze works from pre-history to modern days.

The five-part exhibition: surprises awaiting

The exhibition entitled “Casting for the King: Bronze Art in Angkor” will provide chronological details on bronze works in Cambodia from the very early period of the bronze age to the modern era, Baptiste said.

The first part about the early period from the Bronze Age to the pre-Angkorian era will speak of the origins and the emergence of bronze metallurgy in Cambodia and the first works produced with this alloy.

According to Baptiste, bronze has been extensively used in Cambodia during the middle-end of the bronze age—that is, 1,500 years or so BC. Recent excavations found sources of cooper-ore supplies in the country such as the Chaaep site in Preah Vihear province. Several items found at the site will be on display in France.

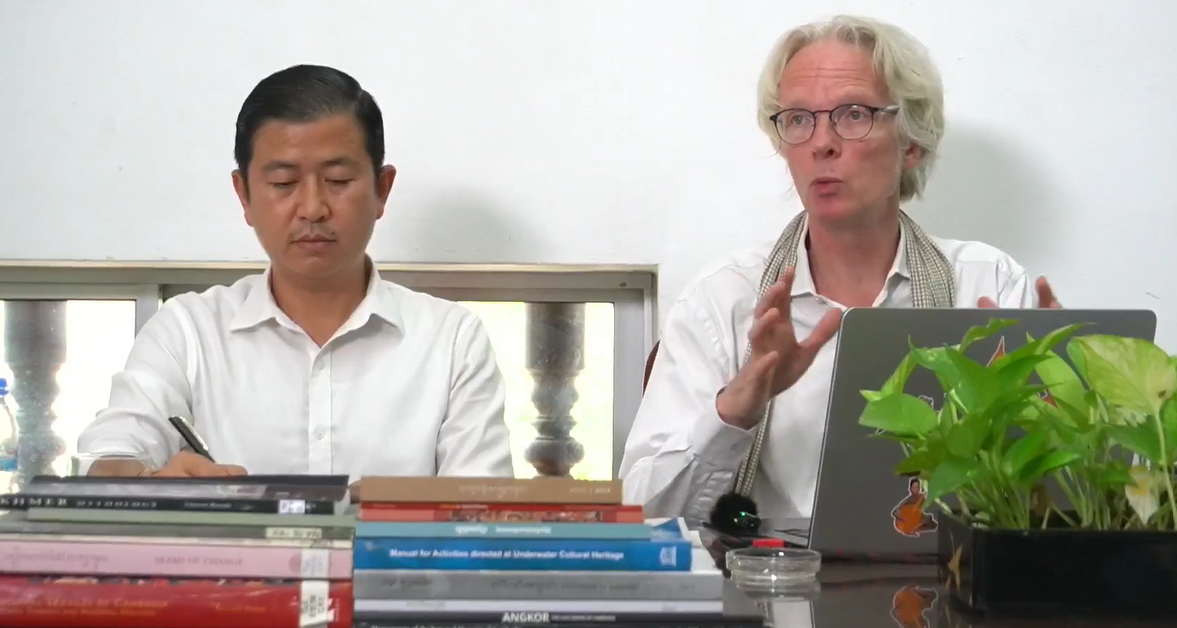

Pierre Baptiste (R), curator of the museum’s South-East Asia Collection, speaks during a recent lecture on museum cooperation in Phnom Penh. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

Pierre Baptiste (R), curator of the museum’s South-East Asia Collection, speaks during a recent lecture on museum cooperation in Phnom Penh. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

“At the beginning of the exhibition, we want to surprise the public a little bit,” Baptiste said. “They think they will come and see an art exhibition and, suddenly, they will be in front of fragments of alloy, metal slag, things that are not at all beautiful to see but which are meaningful to understand ancient metallurgy,

“The purpose of the exhibition is not only to show beautiful objects but also to [help people] understand the whole process of bronze casting, from mining to copper and other metals, to produce the objects and then have them worshipped in the temples,” he said.

In the first section of the exhibition, the visitor will see the oldest Buddhist representations (7th-8th centuries) during the pre-Angkorian period, which testify to the influence of the Indian civilization in the region. The statues of Buddha and Bodhisttva were casted with lost-wax techniques, Baptiste said.

This section will also show Hindu art and Buddhist art through the construction of the Phnom Bayang temple in Takeo province, which has been studied by French archaeologist Henri Mauger. Several bronze items from different periods were found at the temple, Baptiste said.

“We want French people who know nothing about Cambodia to understand how bronze was used in the context of the ritual life of the temple, and what this might have looked like in the temples during the early period,” he said.

“Casting for the King” will be the main theme of the second part of the exhibition, which will deal with the link between bronze and king and aristocracy. According to Baptiste, the entire history of bronze casting is connected to power and the royal power at the top. Evidence could be found on the objects with inscriptions and will be unveiled at the exhibition, he said.

Another evidence of this is the presence of a workshop that was located right next to the royal palace in Angkor Thom city, which shows the connection between royal power and bronze casting. As Baptiste explained, the work conducted by Brice Vincent at the north wall of the palace revealed the casting process as well as the gilding process of the time in which mercury was used—Vincent is an archeologist specializing in metallurgy who is in charge of the Siem Reap city office of the École Française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO).

The third part of the exhibition “Honoring the Gods” will show items from the Angkorian period (9th-15th centuries) that was the peak of Khmer power and during which the use of bronze developed considerably. This will also show the Hinduist and Buddhist iconographies that reflect Khmer culture through examples of bronze art objects.

Bronze used in daily life and for ritual rites will be shown as well, Baptiste said.

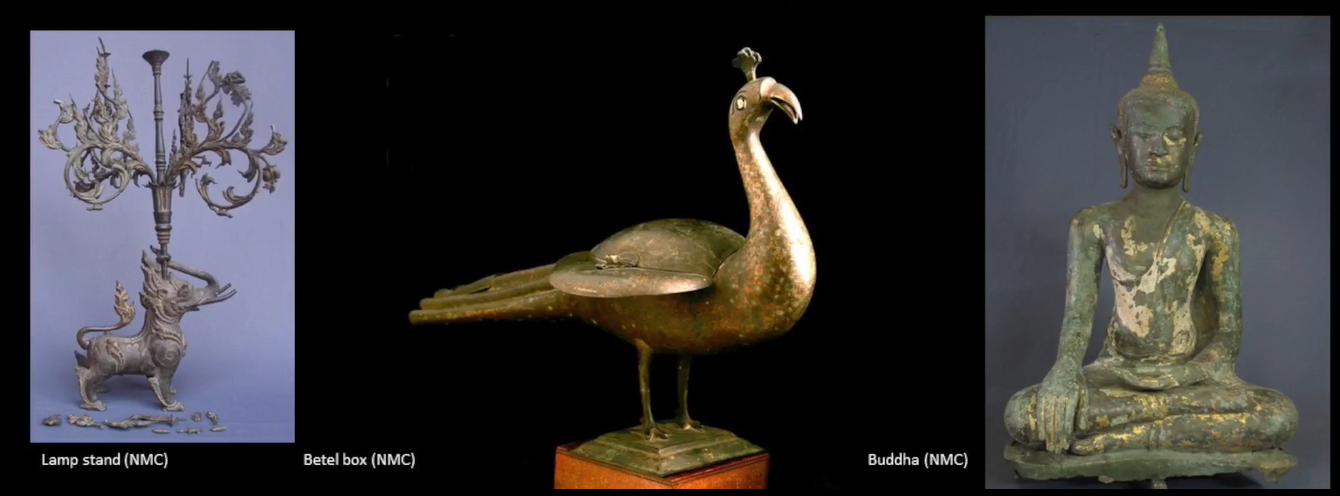

127 bronze object lent by the National Museum of Cambodia will be displayed at Guimet. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

127 bronze object lent by the National Museum of Cambodia will be displayed at Guimet. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

And then, he said, while touring the section on the fourth theme New World, New Places and New Faith, the visitor will be able to understand more about the changes that occurred at Angkor, the abandonment of the capital city of Angkor, and the new capitals that would be located in the southern part of Tonle Sap Lake: Longvek, Oudong and Phnom Penh.

“We will try to show that bronze casting was influenced by these new moments in the history of Cambodia,” Baptiste said.

The iconography from the post-Angkorian period until today has been mainly dominated by Theravada Buddhism—the religion currently practiced by most of the population in the country, Baptiste said. Items reflecting external influence in the country will also be displayed.

The section in the exhibition will be the transition to modernity reflected in objects casted in the 20th and the 21th centuries in order to show the continuity of bronze casting in Cambodia, Baptiste said.

The Vishnu of West Mebon: chronicle of a renaissance

The main feature—and masterpiece—of the five-month exhibition at the Musee Guimet will be the Reclining Vishnu from the West Mebon temple that will be displayed in the last section of the exhibition.

“We really hope that the exhibition will be a great success for the promotion of Cambodian arts, the knowledge people will get of the richness of Khmer Culture,” Baptiste said.

In this last section, visitors will learn about the iconography, the temple, the details of the nearly 6-meter-long bronze statue of Vishnu, the connection between the statue and the temple, and the circumstances of the discovery of the statue.

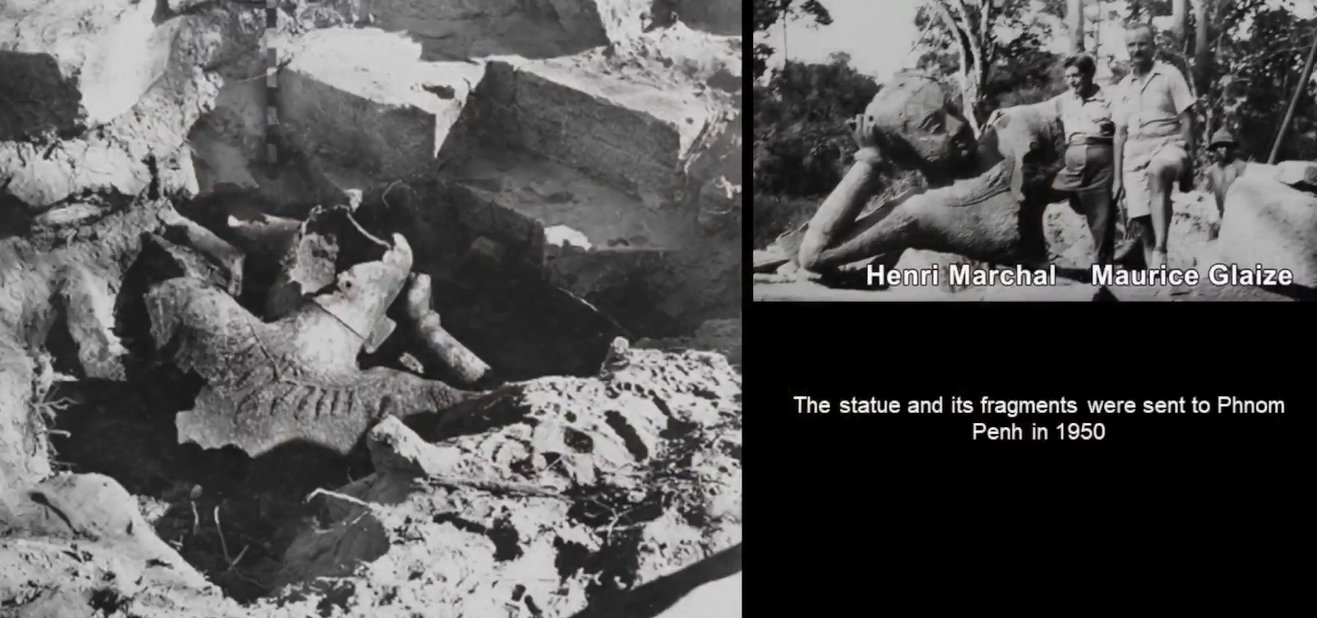

The statue was discovered in December 1936. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

The statue was discovered in December 1936. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

As Baptiste explained during the lecture, the 11th century statue represented Vishnu resting on the Serpent of Eternity.

In December 1936, the pieces of the statue were found by a Cambodian living in the area and who said at the time that he had had a dream, and that in that dream, the Buddha had asked him to help him get free from where he was. The man then dug in the central part of the West Mebon and discovered the remains of the statue, which was not a Buddha but Vishnu, Baptiste said.

The statue was dug out by EFEO archaeologists Henri Marchal and Maurice Glaize, and kept at the artifact storage facility Conservation d’Angkor. Then in 1950, the statue and fragments found at the site were transferred to the National Museum in Phnom Penh.

The structure where the statue of Vishnu was found was the 100-square-meter West Mebon temple, which was similar to other temples at Angkor. It had been built on a site surrounded by water in the vast water reservoir West Baray, which was connected to the bank first by a wooden pathway and later on by a sandstone and laterite one.

According to Baptiste, it seems that, when the statue was put on the site in the 11th century, there was no temple although the statue might have been protected by a large building as pieces of wood and ceramic tiles were found at the site.

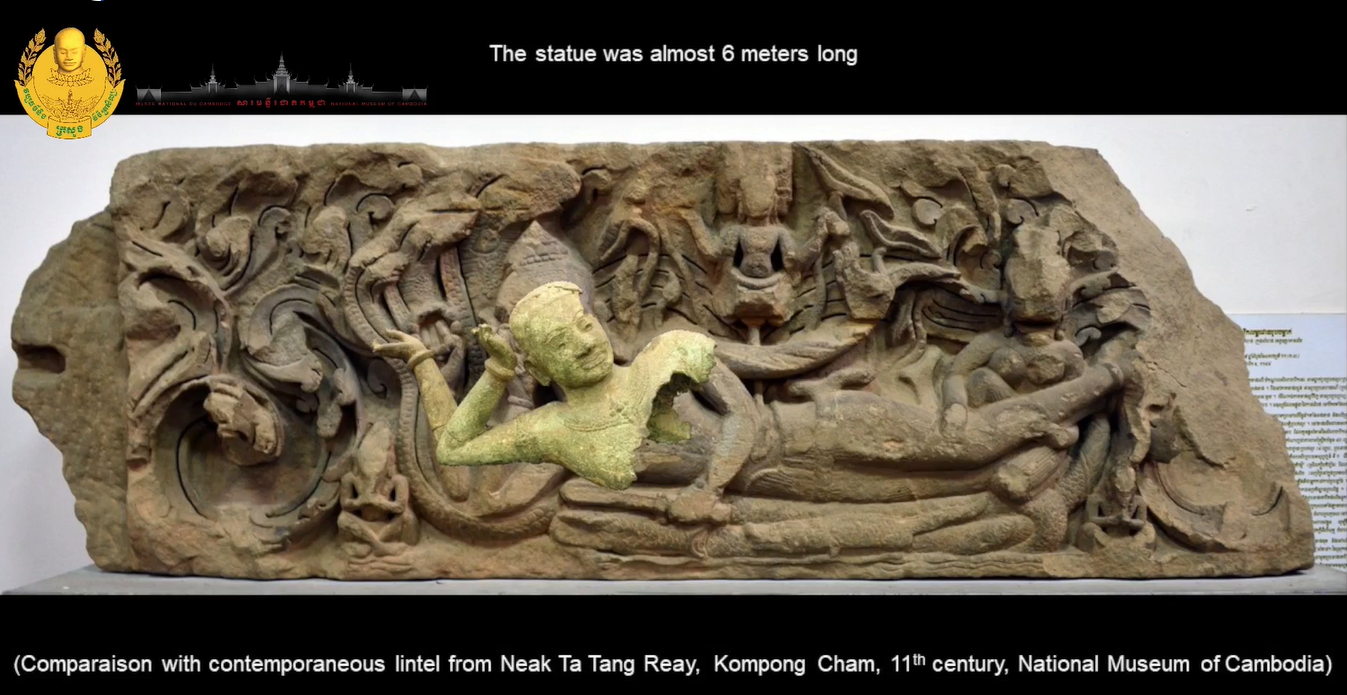

Since there are only upper parts and some fragments of the statue left, in order to understand its posture, comparison was made with bas-reliefs, that is, scenes sculpted in stone, during the same period. For example, the sculpted lintel of the Neak Ta Tang Reay temple in Kampong Cham province enabled to conclude that many parts were missing.

As Baptiste explained, only 25 to 30 percent of the original statue of the Reclining Vishnu remains. If other parts were included such as Vishnu’s wife Lakshmi, the head of a naga, Brahma sitting on a lotus flower, the percentage could be reduced to maybe 15 percent, he said.

Comparison is made with artefact from the same period to understand the full position of the statue. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

Comparison is made with artefact from the same period to understand the full position of the statue. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

Addressing the issue of why only the head of the bronze statue remains, Baptiste said that maybe looters thought the head of Vishnu was too precious to recast it or to be reused. “This is a mystery,” he said.

During the exhibition in France, the virtual image of the statue will be shown but as an hypothesis since the original pose of the statue is not yet known, Baptiste said.

Prior to cooperation on the restoration of the Reclining Vishnu, the Musee Guimet conducted between September and November 2020 a preliminary study on the statue with the EFEO and scientists of the French museum restoration and research center Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (C2RMF). Fragments of the statue stored at the Musee Guimet were radiographed to provide information on their inner structure, and other techniques were also used to analyze the bronze pieces.

Preliminary study was also conducted on fragments discovered with the statue in 1936 and found in the National Museum of Cambodia’s storage inventory in Phnom Penh.

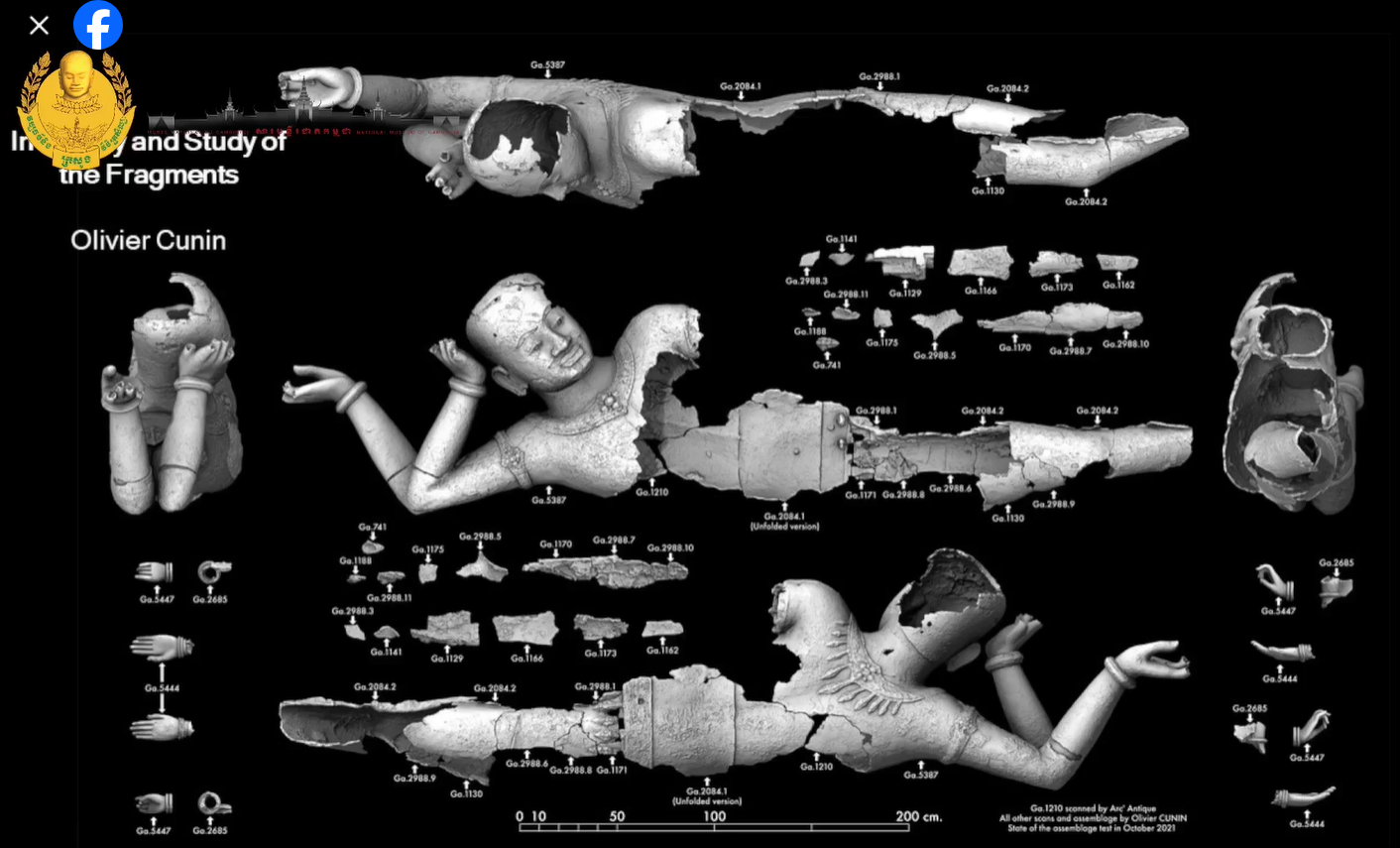

“There is a large number of fragments of all sizes, from very small to rather large, which have been identified, measured and studied so that we can find their actual position in the statue,” Baptiste said.

Computer scanning conducted by Oliver Cunin of the APSARA National Authority who has also been involved in the study show that the statue of Vishnu was originally five-to-six meter long. It also showed that the remaining pieces are mostly from the back of the statue and none of them segments of the arms or other parts of the statue.

According to Baptiste, those fragments were badly preserved in the past and are very fragile. “Probably we really have to preserve them separately and only provide a virtual image of what could have been the statue when it was whole,” he said.

During the restoration of the West Mebon temple, a preliminary study of the structure of the statue had been conducted.

The computer scanning done Olivier Cunin shows many parts of the statue were missing. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

The computer scanning done Olivier Cunin shows many parts of the statue were missing. Photo taken from live video on Facebook page of the National Museum of Cambodia

A project many years in the making

Plans to send the Reclining Vishnu to France had been in the works since 2018, Baptiste said. But due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is only in mid-May 2024 that the statue and some of its fragments have finally been sent to France, he said.

At C2RMF in Paris, the statue will go through 3D scanning and extensive analysis between June and September 2024, Baptiste said, Then, from October 2024 to February 2025, it will be studied at a laboratory in the city of Nantes in France, which specializes in the conservation of large statues.

Three Cambodian conservators are accompanying the statue and will take part in the conservation process.