UNDP Report -- Blueprint to Making Cambodia’s Economy Benefit from Natural Resource Preservation

- Jazmyn Himel

- November 26, 2019 10:09 AM

PHNOM PENH—The solution to Cambodia’s vulnerable economic position to climate crises could lie in the nation’s declining agricultural sector.

And more specifically, in the country’s forests and the rural communities that depend on them, according to a report of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) released Nov. 21.

“Economic data suggests a tightening of the agricultural sector’s relative productivity, and in turn, an oversupply of labor in core areas that may be depressing income levels somewhat,” according to the UNDP’s “Human Development Report Cambodia 2019.”

The country’s labor market used to be dependent on the agricultural sector, as seen in 1993 when an estimated 80 percent of the population worked in agriculture.

By 2017 however, that number had decreased to 40 percent according to a study by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

The labor market has grown increasingly dependent on sectors located in urban areas, such as the garment industry—currently the country’s largest employer.

Forests and the Role of Communities

The UNDP report suggests that protected forest areas managed by communities living in those forests could not only promote environmental sustainability, but also generate financial prosperity for the nation and equity for future generations.

If business continues as usual, climate change could “affect labor productivity and GDP growth: It may cause a 10 percent decrease in GDP growth,” said UNDP environmental policy specialist Moeko Sairo Jensen in interview.

Forests are not only Cambodia’s main natural resource but they also are necessary for the mitigation of climate change. As UNDP country economist Richard Marshall explained in interview, they “regulate the ecosystem, guard against shocks and mediate weather events.”

But the role of forests spans beyond mitigation as it accounts for the livelihood of some 80 percent of the country’s population living in rural areas and, the report notes, “highly depend on forests.”

Those local economies could benefit by building, the report read, “on the effective use of forests as a modern resource to drive higher value-added activities ranging from commercial forestry to high-end furniture to eco-tourism.”

The UNDP report stresses the importance of providing these communities with incentives to take on preservation efforts, as their involvement would be the most effective safeguard and monitoring due to their close vicinity and understanding of the forests.

The Economic Model Saving Kulen Mountain

According to the UNDP report, Phnom Kulen mountain serves as a successful example of community forest management.

Forest cover on the mountain has dropped from 42 percent in 2003 to 25 percent today due to cashew-nut farming, the report notes.

The mountain is a highly-important religious site for Cambodia and houses a watershed in Phnom Kulen park that is “critical for providing year-round water [and] all 36 headwaters of Siem Reap river,” according to the Ministry of Environment.

This has prompted the Archaeology and Development Foundation (ADF) to work with the government to develop ways to protect the Kulen National Park’s natural resources.

The 2018-2027 Plan of the Ministry of Environment (MoE) outlined its multi-faced approach to preserving the mountain.

First, through strengthened law enforcement: The MoE hired local residents as park rangers and provided income and therefore incentive to monitor and prevent illegal forestry practices.

Then, in order to promote development while ensuring sustainability, alternatives to cashew farming and illegal logging were taught and provided to villagers by the ADF. This has included animal raising, small-scale mushroom farming and seasonal vegetable growing.

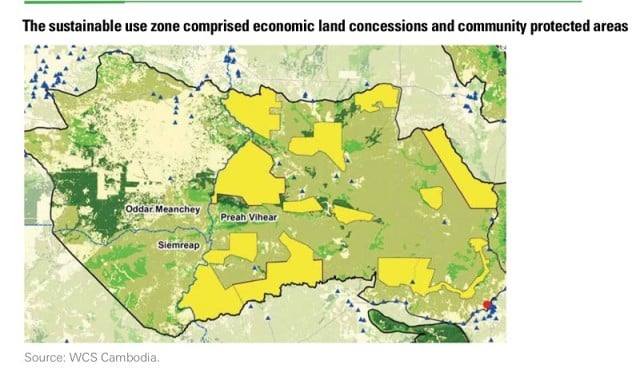

Secondly, sustainable zones were established by the Ministry of Environment. They were designated as areas for protection or, according to the MoE plan, “areas for local subsistence harvest of natural resources” by park residents.

Lastly, the tourism management strategy has required that private tours of cultural park attractions be led and monitored by trained local villagers so they can be “more actively involved in and benefit from tourism.” Tour concessions profit would be, the plan stated, “reinvested in the management and protection of the park.”

“This not only provides an income stream for the rangers, but it makes me value the asset (according to behavioral economics),” through charging visitors at the park, UNDP economist Marshall said.

“If I go to enjoy an ecosystem, I should pay for its use. Payment towards its preservation: The point is making it a plus, a commercial [one],” he added.

What the Kulen model showcases is how, through cooperation and involvement, rural communities can be the economic and law-enforcing strong heads of preserving the natural resources that are integral to the future of Cambodia.