Education Puts an End to Early Marriage and Poverty in Ratanakiri

- By Heng Sreylin

- and Kheav Moro Kort

- May 9, 2022 8:51 PM

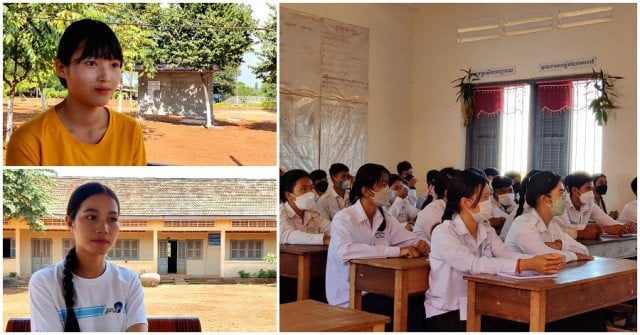

Going against the flow of well-established traditions, more young indigenous women are getting involved in high education, often far away from their communities

RATANAKIRI –Young Indiginous women in Ratanakiri province express their willingness to pursue higher education in universities after graduating from high school. For most of them, education is the only way to escape forced marriage at an early age, poverty, narrow-mindedness and underdevelopment of community.

Ting Phaek, a 12th-grade student at Bar Kaev High School, in Bar Kaev district, Ratanakiri province, dreams of continuing her studies at university. This native Tampuan girl, an ethnic group counting around 31.000 people in the Kingdom, routinely gets up before 7 a.m., going to school by motorbike, 20 kilometers away from home.

By dedicating time and energy to her high-school education, the young girl hopes she will achieve good grades and be able to seize opportunities for pursuing a major in law at the university in Phnom Penh. “I have no money for my upcoming studies, so I’ll have to work on top of my studies because my family is very poor and can’t financially support my project,” the 19-year-old Phaek explained.

Because of family culture and local traditions, being forced to get married at a young age and earning a living at the family's farm still largely prevent indigenous youths from having full access to education opportunities. Phaek and many other young women want to push for some modernity in their communities. She thinks learning is key to building a better life and shall come before marriage. For Phaek, who wants to be a lawyer, finishing high school and pursuing higher education will be more beneficial than getting married in the future.

Like Phaek, Romam Oun, a young descendant of Jarai indigenous people, wants to use her knowledge and skills to develop her community. She is the only one among her three brothers and sisters to study at a higher level than grade 11 and now dreams to study management and business. All of her siblings were married at the age of 15 and 16, even before they finished their secondary level of education.

Oun said that she received her parents’ support to finish high school and then continue her studies in Phnom Penh. But the 18-year-old Jarai native remains under pressure from people in her community, as the elders in the village tend to value marriage more than the education of their children.

Despite going against the flow of well-established community traditions, the two indigenous girls still want to continue their studies in Phnom Penh, giving them the best chance to achieve their dream.

In the last few years, an increasing number of ethnic minority youths seem to prioritize education over marriage as their parents are more aware of the value of education.

Huon Khan, the founder of the Brao Indigenous Youth Group, sees this trend as positive as some people, at their individual level, begin to understand the issue of getting married too early and would likely prefer to study hard as a way to participate in the community’s development.

"As soon as our community begins to understand this issue and attract strong support in promoting education for ethnic youth, our community will then grow stronger, both in economic and social perspectives,” said Khan.

Although the trend of starting to value education is perceived as a positive change by some indigenous people, high education among the youth in ethnic minorities is not widespread yet.

"In remote areas specifically, school dropouts [for indigenous youth] are still as high as they used to be in the past. There hasn’t been much change there yet, said Huon Khan. Because of their ancient understanding, it is hard for [indigenous] parents to see the value of their children's education.”

Young indigenous people's school dropouts take root in their parents’ own education, livelihood issues or family pressure that requires their children to marry and have children in order to work in the farm fields.

Plan International Cambodia, an organization promoting children’s rights, is currently focusing on indigenous children and youth, to get higher education opportunities and contribute to the development of their community. In addition to Plan, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports has also partnered with UNICEF Cambodia and CARE to provide multilingual education to indigenous girls and boys.

In 2016, they launched multilingual curriculums to promote education in five indigenous languages (Pnong, Karet, Kreung, Tampuan and Brao) in Mondulkiri, Ratanakiri, Kratie, Stung Treng and Preah Vihear provinces.