First Generation of Living Heritage Masters is Aging and Sick

- By Po Sakun

- January 3, 2024 11:55 AM

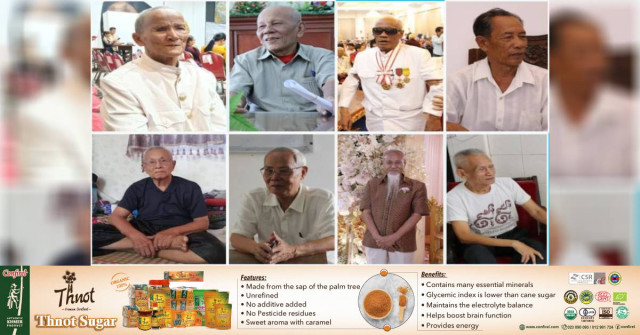

PHNOM PENH – The last eight traditional art masters of the first generation, who were granted the Living Heritage Status in 2012, are aging. Some of them live in poverty and others suffer from chronic diseases.

The Living Heritage Status was first granted by King Norodom Sihamoni to 17 masters who developed outstanding skills in Khmer traditional arts, from dancing to music and painting. As of the end of 2023, only eight of them were still alive.

Originally from Battambang province, Chea Hea, 93, specialized in making masks for the Lakhon Khol theatre. This type of performance combines dance, music and traditional costumes, including many masks representing deities.

Chet Chon, 88, is a former professor of Pali language – the sacred language in Theravada Buddhism – Sanskrit language and philosophy at Preah Sihanoukraja University. Originally from Takeo province’s Tram Kak district, he received an honorary doctorate in Pali on Sep. 4, 2011. He also received a medal for education in the field of Khmer cultural arts.

But Chon’s health is declining and he has severe hearing problems.

Tea Van, 84, was a Khmer language and Sanskrit teacher at Preah Suramarit Buddhist University. Originally from Kandal province’s Koh Thom district, Van made every effort to educate his students, in terms of knowledge, skills and wisdom.

Chan Sim, 84, has taught the art of sculpture since the Sangkum Reastr Niyum era. Originally from Phnom Penh city, Chan Sim was a professor of art at the Royal University of Fine Arts until his retirement.

As a sculpture enthusiast, he tried to maintain the rules of sculpture on wood, stone, or cement. He had been teaching at the Faculty of Visual Arts - Architecture at Norton University and at home since 1959.

He also compiled a two-volume book entitled “Khmer Sculpture Scale for Drawing and Carving”. During his career, Chan Sim created about 200 sculptures and has trained dozens of students, including 10 Lao artists.

Back then, he received the Sangkum Reastr Niyum Silver Medal and an honorary degree as an actor in 2002. Two years later, Chan Sim was granted the “Master of Khmer Culture and Arts” status from the Royal Academy of Cambodia.

Kong Nai, 78, is an expert in Chapey Dang Veng, a traditional two-string instrument similar to a long-necked guitar. Originally from Kampot province, he was the third Cambodian to receive the Fukuoka Prize from Japan. He has been sick and bedridden for many months, and has difficulty perceiving notions of space and time.

Men Prang, 77, is a former professor at Pali school. Back then, he researched the Khmer traditional ceremonies at the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts.

Chet Chorn, 76, is a classical painting specialist. Originally from Prey Veng’s Kampong Trabek district, he taught at the Secondary School of Fine Arts and the Royal University of Fine Arts from 1966 until his retirement.

Chet Chorn also taught at the Faculty of Visual Arts on classical painting and instructed Khmer art styles at the Association of Cambodian Artist’s Friends. He researched the Preah Keo Morakot gallery in the Reamker story. In addition, he also used to work on painting repairs with Polish technicians.

Chet Chorn received many appreciation letters and certificates, and an honorary degree as an actor from 2004-2005.

Peak Chapech, 69, specialized in the art of solo storytelling on Lakhon Bassac. He became popular thanks to his ability to use nearly 10 different human voices and Tro Khmer, a traditional three-string Khmer musical instrument.

However, Chapech’s health is rapidly declining due to his chronic illness, aggravated by the poor conditions in which he lives.

The Living Heritage Status is granted to any individual or group of people based on some qualifications. Those include their highest level of knowledge, skills, talents, techniques, morality, living with dignity, and their masterpieces in intangible cultural heritage. Most importantly, living heritage refers to those who are willing to conserve and transfer their knowledge to the next generations openly.

According to the Royal Decree on the Living Heritage Status of Cambodia, the grantees must be committed to representing the intangible cultural heritage in the region and community.

People with living heritage status must have their code of ethics as determined by the Prakas of the Minister of Culture and Fine Arts. National title will be granted to them with the recognition by Royal Decree requested by the Prime Minister.

Benefits gained from this status include monthly pay as well as some supporting materials and budgets for their training and research.

To preserve Khmer traditional arts, an additional nine masters were granted the Living Heritage Status in 2023. They include professionals of traditional dances, indigenous music, or silk ceiling waiving.

Originally written in Khmer for ThmeyThmey, this story was translated by Rin Ousa for Cambodianess.