How Extensive Were the Roads of Angkor?

- By Cambodianess

- April 30, 2023 6:00 PM

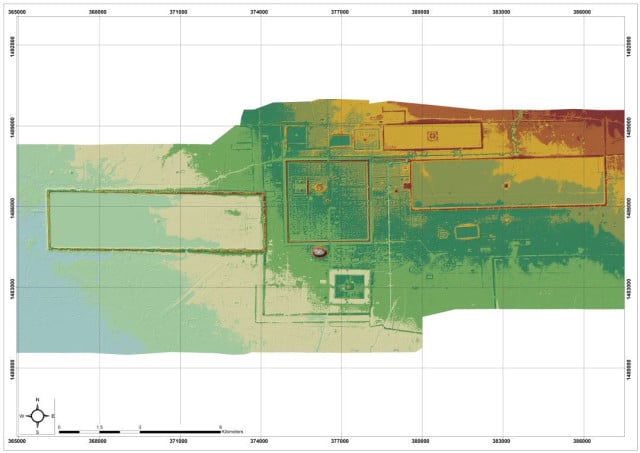

SIEM REAP - Roads strengthened the expansion of the Angkor era. Stretching approximately 3,000 kilometres in total through different geographical areas, strong bridges, quality roads, engineering ingenuity, sheer will as well as favourable natural resources allowed the city of Angkor, central to the Khmer Empire, to prosper.

With a decade of experience in archaeology and history, Im Sokrithy, an expert from the APSARA National Authority, joined ThmeyThmey News and Blue Art Centre in Siem Reap city during the Khmer Art from Angkor discussion programme to share research and findings on The Living Angkor Road project.

_1682844971.png)

_1682845057.png)

How did these roads come to be?

Prehistorically, as soon as ancient humans began looking outward from their cave homes and started to live in clusters in the form of communities and villages, the concept of roads emerged. When settlement became more important than hunter-gathering, the need for water for agriculture and livestock demanded a system of roads.

One of the oldest road systems can be observed in the region of Mesopotamia of Central Asia as early as 5,000 years BCE.

In Cambodia, a road system which connected emerging city-states can be visible through scientific studies at around several hundred years CE.

_1682845168.png)

Trades people and their activities travelling between the ancient civilizations of India and China also catalysed the development of the road system here.

Relying predominantly on wind direction to push their ships and the case of monsoon wind changing direction twice annually, Cambodia became a location where mariners had to berth for supplies and wait for a favourable wind to blow again.

It was this kind of disembarkation that cultures were exchanged in terms of medicine, clothing, daily materials and much more.

The Birth of Kilometre Zero

Seeing many city-states acting more or less independently, in 8th century CE, King Jayavarman II began uniting these into one large empire with the city of Angkor at the center. It was during this time that the road system on which we are focusing started to extend outward from Siem Reap. Existing road infrastructure was connected with new ones and noticeable progress can be seen during the 9th century.

Although it happened gradually, the roads cannot grow in length endlessly.

“It is just like transporting electricity. Without having relays in some intervals, the electricity becomes weak,” Sokrithy said.

For those travelling north at that time, the city of Phimai in modern day Thailand’s Nakhon Ratchasima province, was a relay for the city of Angkor before the road continued as far north as the city of Chiang Rai, also in present-day northern Thailand. To the east, the road network extended to Sovannakhet, a city in Laos. Down south, as it almost touched the boundary of Malaysia, the network reached as far as Nakhon Si Thammarat. Turning West, this ancient highway could pass its grip until Kanchanaburi, a Thai city bordering south of Myanmar.

_1682845268.png)

“It is approximately 3,000 kilometres long in total,” Sokrithy said. This excluded the road network in the city of Angkor.

During an interview with the APSARA National Authority, Sokrithy also stated the frequency of “resting houses” along the roads being 4 hours apart through the use of oxcart. The resting houses may provided water, resting and praying areas.

According to the study, villages of the past were not located next to the main road as we would see now. Traditionally, villagers formed their settlement further away while using a smaller road to connect to the main road.

“One section of the National Road 6 leading to Siem Reap city is actually built on top of an ancient road system” he added during the interview.

Engineering the roads and bridges

It is not just the length of the road that counts, but also its quality as well. Beginning by excavating unfavourable soil, engineers filled the bottom layer with large stones and gravel rich in manganese. Upon compression, the upper layers were filled with softer soil for easier passage of people, elephants, cattle and horses.

Through his further observation on ancient bridges of Angkorian time, archaeologist Sokrithy found that stone bridges, such as that of the famous Kampong Kdei bridge in Siem Reap province or Toab bridge in Oddar Meanchey province, only exist within the boundary of modern-day Cambodia for reasons still unexplained.

One prediction would suggest that further bridges from the city of Angkor were constructed using wooden materials making them less effective in standing the test of time. Evidence inside Angkor city also proves the existence of wooden bridges through remnants found at the bottom of some water passages.

According to the same expert, there were three types of bridge that Angkorian people used. “The first one being the stone bridge”, Sokrithy said. “They were made from laterite stones, limestone or a mixture of both.

“The second one being the wooden one while the third one, although they disappear completely now, being the floating bridges”.

By relying on information provided by bas-relief on one gallery of Bayon and Banteay Chhmar temples, wood or bamboo are thought to be tied together to carry elephants and soldiers.

Stone bridges were made strong by having rocks lying downward like staircases along the diagonal line of the water passage’s bank and compact soil running upward from land to the bridge above.

Below the bridge, a layer of softer soil was excavated and replaced by laterite stones. Each column supporting the bridge saw its base being wider at the bottom making it more resistant to the flow of water running through the structure. To further reduce the water strength, stones could be laid ahead of the bridge so that the force of water was reduced.

The longest stone bridge in the area is the Toab bridge measuring 150 meters long and, according to the archaeologist, this might be the limit on how long it can practically be.

“According to an engineering evaluation, this kind of stone bridge could support up to 40 tonnes,” said Sokrithy.

Ancient industry along the roads

“From day to day, we find more evidence in regard to this”, the archaeologist said of the ancient metallurgical industry in Preah Vihear, a northern Cambodian province bordering Thailand.

Being next to Wat Phu, a ruined Khmer Hindu temple in present-day southern Laos, this area was a location of trade conducted by minority populations for the Khmer and Cham population.

Although not among the earlier people to make use of metallurgy, evidence of blacksmithing could be seen, yet with lower metal quality. It was not until around the 10th century CE that the knowledge of metal work noticeably improved which also contributed greatly to the development of the Angkor era.

Apart from pottery, salt mining was also a prime activity when it came to the industry along the roads in Phimai as this location contains a large deposit of salt. Since the ocean remains a long distance from Angkor city, relying on the salt supply from this northern city was crucial.

Trade was conducted when people from the north demanded aquatic products from Tonle Sap lake and the people from the south required salt from the opposite direction.

Interviewed in Khmer for ThmeyThmey News, this story was translated for Cambodianess News by Ky Chamna