Koh Ker: the Romance of Nature and Culture in Archaeology

PREAH VIHEAR Province — Standing in the silence of nature and engulfed by the roots of trees that have spread over their every sandstone and brick structures over the centuries, the temples of Koh Ker are prime examples of the tug of war between nature and the country’s monuments that has gone on for centuries every time Cambodians stopped using or caring for one or the other.

_1713328615.png)

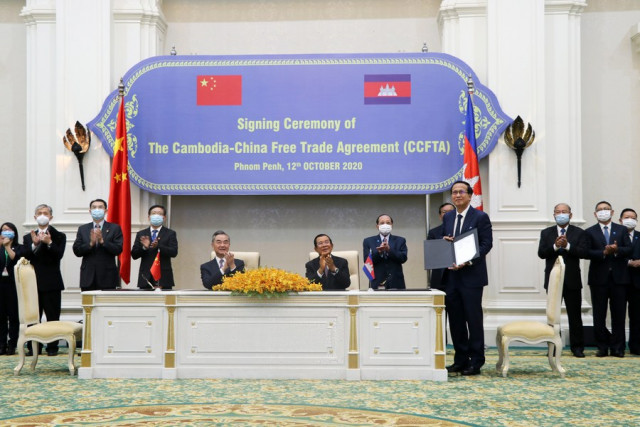

Prasat Pram, whose Khmer name means five temples, is in fact a group of five single-tower Hindu temples located on the Koh Ker Archaeological Site, which was inscribed on the UNESCO’s World Heritage list on Sept. 17, 2023.

Situated about 350 kilometers from Phnom Penh and about 120 kilometers from today’s Angkor Archeological Park, Koh Ker was founded by King Jayavarman VI. This king, who reigned from 928 to 941, had decided to build his own capital city for his kingdom. Set about 120 kilometers from Angkor, and named Lingapura or Chok Gargyar, the city would only serve as the country’s capital until 944, when the court returned to Angkor.

Caption: People visiting Prasat Prang (Prang temple) during the 2024 Khmer New Year. This is one of the most recognisable step pyramid in Cambodia alongside Bakheng, Bakong and Baksei Cham Krong temple.

At Koh Ker, Prasat Pram has so far been overshadowed by the nearby larger temple of Prasat Prang that, with its impressive pyramid shape, tends to attract more visitors. Still, Prasat Pram is definitely worth visiting. Its arrangement comprises of a line of three main structures and another line of two secondary structures.

_1713329325.png)

The presence of people’s offerings may signify that these temples have been visited and worshipped from time to time.

_1713329411.png)

Pram temple was the creation of King Rajendravarman during the 10th century CE. Normally, ancient monuments like these generally have one or two secondary buildings situated at the front labelled by experts as “libraries”.

However, for Prasat Pram, the two secondary buildings are contrarily situated at the back with the three main towers situated at the front. All real doors face east with three false doors facing the remaining three directions.

One of the towers still holds well-preserved lines of ancient inscription on its door frames. The inscription tells about a senior guru who offered his admiration to the gods and the kings. These lines of text are crucial for the study of Sanskrit and ancient Khmer literacy.

_1713329737.png)

Reports from French researcher Lunet de Lajonquière from 1902 give out a picture that there were bas-reliefs and some texts carved onto the ornamental sandstones such as those of lintels or colonnettes. However, these were likely to be destroyed during the conflicting times.

_1713329817.png)

In the course of the centuries, pre-Angkorian and Angkorian builders used bricks, laterite and sandstone to build the temples of the Khmer empire. Sandstones were generally used to create architectural features such as lintels, pediments, door frames or colonnettes on which were sculpted intricate elements.

Bricks tended to be used for the general shape of a structure. Laterites, being hard stones, were used for layering the foundation and outside walls. Unfortunately, the Prasat Pram temple seems to have been left incomplete with some stone surfaces yet to be sculpted.

Caption: The serpentine tree at Ta Prohm temple.

Caption: The serpentine tree at Beng Mealea temple.

Like nature did at the temples of Ta Prohm and Beng Mealea in Angkor Park, two of the five towers of Prasat Pram are almost entirely swallowed by the serpentine-like tree roots and branches, creating an impression of the monument being old and deteriorated, while at the same time giving a clear example of genuine human engineering that has stayed the test of time with a technology more than a millennium old.

_1713330331.png)

Caption: Mounir Bouchenaki, member of the International Coordinating Committee of Angkor (ICC-Angkor) and of the ad hoc expert group for conservation. Photo: Lay Long

“The Angkor site has the characteristic of a specific harmony between what was built and what Nature has done,” said Mounir Bouchenaki, a member of the International Coordinating Committee of Angkor (ICC-Angkor) and a member of the ICC ad hoc expert group for conservation. “This is a harmony that is considered to also be respected: This is an alliance between Nature and culture.

“Nature is what the gods have given to this Earth,” he said. “Culture is what men have built. It is important in some places to keep the testimony as they are touched by time. This is called the romance of archaeology.”

Setting foot at Koh Ker is like stepping back in time, especially during the monsoon season when thick canopies, tangling tree branches, moss and soggy soil as well as gloomy sky create a unique atmosphere.

Stone pillars, some of them several meters high, halfway falling, and temples with sections lying on the ground are a reminder of what Nature can do when there is no human intervention to preserve even a sturdy stone structure.

According to archaeological research, the region of Koh Ker, although largely abandoned, was still inhabited by people from the 10th century to the 15th century. The reason why Koh Ker remained an important city for centuries was perhaps due to its geographical location as it connected the region of Angkor to Wat Phu temple in present-day Laos as well as to other parts of the Khmer Empire.

This UNESCO World Heritage site includes 196 historical sites, 76 temples as well as a number of roads, ponds, reservoirs and dikes.

A one-day ticket to visit the Koh Ker site is $15 per adult for foreigners and free for Cambodians. The tickets can be purchased onsite.

Related stories:

The Beauty and Ruin of Smaller Temples at Koh Ker

UNESCO Lists Koh Ker Temple Region as World Heritage

Banging the Drum for Koh Ker UNESCO Inscription