Teaching Children of Countries in Conflict, Past and Present, How to Deal with Them

- By Michelle Vachon

- March 13, 2024 11:55 AM

PHNOM PENH — In a “normal” world, the people who recently travelled from several developing countries to meet in Phnom Penh might have discussed how to help prepare the poorer students with little or no access to mobile phones and computers so that they are not left behind in the Third Industrial Revolution.

However, during the regional conference of EdJAM held in Phnom Pehh in February 2024, what they talked about was how to teach students and support people of their countries who went through or are currently dealing with conflicts and war. The team researching how the Palestinian community has been treated in Jerusalem since the early 2000s had to leave early due to Israel’s war against Palestine.

The name EdJAM stands for Education, Justice and Memory Network. “Some years ago, a group of scholars from universities in Great Britain…met with people…from the global South who have been working to…develop educational and teaching tools to help deal with past violence," said Chea Sopheap, executive director of the Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center that hosted the conference in Phnom Penh. “So, we came together and discussed how we could work jointly.”

People at the conference included teachers from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)who have developed an application, are using social media and holding events to help people look into what has led to violence in the past and present and, they hope, help curb conflicts in the future. It is believed that, since 1996, those conflicts in the eastern part of the country have caused the death of approximately 6 million people. And at this point, around 7 million people have been displaced inside the country due to poverty and the threat of violence.

In Jamaica, the project consists of studying and making students aware of the history and culture of the Maroons. They were African people brought to the island by the British in previous centuries to work as slaves on the island's sugar-cane plantations, and who had managed to escape and take refuge in the interior of the island. Since the country obtained its independence in 1962, they have remained in their own villages that have special status.

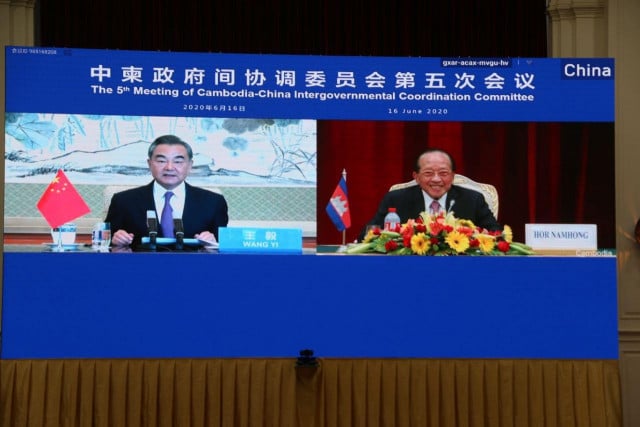

Members of EdJAM network speak of their project on the situation of the Palestinian community in Israel over the last decades. Photo_ Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center

Members of EdJAM network speak of their project on the situation of the Palestinian community in Israel over the last decades. Photo_ Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center

In Pakistan, a documentary film is being done on Lyari, a neighborhood of Karachi where around 1 million people live and where the police authorities hardly take action when violence erupts or criminals hide there. While residents say violent incidents happen less often these days, the fear remains. The project’s goals include encouraging the various communities to talk to each other to address the situation.

And in Cambodia, the NGO Youth for Peace (YFP) conducted a study on the Samroung Knong Security Center that was a Khmer Rouge prison in Battambang province. It is believed that 10,008 prisoners were killed at that facility during the Pol Pot regime of April 1975 to January 1979. The project included interviews with former prisoners. Funded by EdJAM, it was done with the support of several government ministries and institutions including the Royal University of Phnom Penh, and in cooperation with the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO).

YFP also published a 102-page book on the prison entitled “Samroung Knong Security Center” with black-and-white illustrations. In the preface, YFP Executive Director Man Sokkoeun thanks people who will read the book as, he writes, “[i]t shows that we are all contributing to the work of memory and preventing this crime from happening again, and that is for social justice, development and security for all.”

Young Cambodian filmmakers are also doing a documentary film on the M-13 Khmer Rouge prison with the support of the Bophana Center and funding from EdJAM. According to research conducted by the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, the prison was the prototype Khmer Rouge prison where guards were trained in torture techniques. Located in Kampong Speu province, it was opened in 1971 as the Khmer Rouge soldiers were fighting the Cambodian government army and four years before they took control of the country.

The film, which will include interviews with survivors of this prison, will be accessible to the public on the multimedia app on the history of the Khmer Rouge, which was developed by the Bophana Center through EdJAM support, said Cheap Sopheap.

The EdJAM conference in Phnom Penh was held at the Bophana Center by its Cambodian partners: the Tuol Sleng genocide Museum, Youth for Peace and the Bophana Center.

As explained Peter Maning, a British sociologist who set up the network and project four years ago with British sociologist Kate Moles, “this is quite a distinctive kind of project…Research is a very important part of the work that we are doing. But because it’s funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council in the United Kingdom (UK) and it’s part of a [UK] government initiative called the Global Challenges Research Funding Collective Programme…we are in a bigger family of development-facing research.

“The broader sort of orientation is essentially how we can support research and advocacy in the name of sustainable development goals…trying to think about how we can contribute to peace, justice,” Maning said. “It’s a question of memory too…So what we’ve been trying to do for the last four years is looking at new ways to…teach these histories.”

Because even when conflicts are over in a country and peace has returned, past events continue to affect the people who lived through them. As researchers and psychologists have discovered, the memory and trauma of what people lived through get passed on to their children and grandchildren. “When I first came [to Cambodia], the moms would say to their kids ‘if you don’t eat your rice, [Khmer Rouge leader] Pol Pot will come and get you,’ and things like this,” Maning said.

“People remember,” he said. “They remember the history but not in ways that are visible, immediately visible.” During the 2010s, Maning spent several years in Cambodia as a researcher and observer of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. His book “Transitional Justice and Memory in Cambodia, Beyond the Extraordinary Chambers” was published in 2017.

Members of the Education, Justice and Memory Network (EdJAM) pose for a group photo during their conference in Phnom Penh in February 2024. Photo_ Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center

Members of the Education, Justice and Memory Network (EdJAM) pose for a group photo during their conference in Phnom Penh in February 2024. Photo_ Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center

During the conference, participants discussed the situation in their countries and the programs and tools they developed to help their people deal with daily reality.

And their task is far from over, said Sopheap. “We need to learn more and we need to work more even if these are painful things that we are dealing with,” he said. Without talking about this, without making people understand this, we have no way to end this tragic experience. How many lives are being lost, how many children become orphans, how many women become widows, how many patients in hospitals. And people cry.

“I don’t know how to describe this,” Sopheap said. “But as human beings, why don’t we find ways to create peace, to live together in harmony. We need to work more.”