Alain Forest: “It is Always an Achievement for Novelists to Make Fiction Seem More Real than Reality”

- By François Camps

- February 16, 2023 10:20 AM

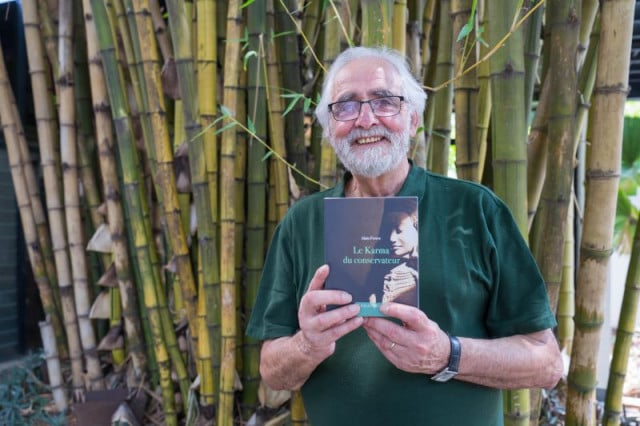

PHNOM PENH – French Professor Emeritus and expert on Cambodia’s history Alain Forest had his latest book, “Le Karma du conservateur” (the curator’s karma), published in November 2022. At 75 years old, he has decided to try his hand at novels.

Forest, who lived in Cambodia in the 1960s, published in 1980 a study that has become mandatory reading for any historian studying the French administration in Cambodia. Entitled “Le Cambodge et la Colonisation Francaise” (Cambodia and the French colonization), the 542-page book focuses on the period of 1897 to 1920 during which the French administration set its patterns, he said. Among other works, he published in 1992 a study on Cambodia’s protector spirits, the neak ta, and in 2012 the book “Histoire religieuse du Cambodge” (religious history of Cambodia) in which he explains when and why Cambodians came to embrace diverse religions over the centuries.

So, even though Forest set his characters in a historical context, writing a novel has been quite a departure from his usual works. During a recent visit to Cambodia, Forest on Feb. 10 agreed to discuss the plot of his book in which ancestral beliefs that may date from the Angkorian era meet the meticulous work of French curators of the 1930s.

François Camps: Would you please summarize the plot of the book?

Alain Forest: It is the story of a young married couple, Daniel and Julie, who arrive in Siem Reap in the early 1930s. Daniel works as an architect for the Angkor Conservation [where are stored and preserved artifacts found at Angkor] and Julie is a sociologist. While he comes to work on the restoration of the temples at Angkor, she wants to dedicate her time to studying Cambodian villages in the countryside. Both of them very quickly integrate into the local community. But after a few months, Daniel starts to behave awkwardly: He has become terribly jealous of his wife, who decides to leave him…Daniel ends up committing suicide.

François Camps: But the book is not a crime novel, isn’t it?

Alain Forest: No, it is not. It is inspired by the story of Georges Trouvé, who indeed was a French archeologist who committed suicide at Angkor after his wife left him. The case has never been fully resolved. But the “Le Karma du conservateur” is truly a story that comes straight out of my imagination, not a real story.

François Camps: What made you write this book?

Alain Forest: First of all, it was a relaxing thing to do “at the end of my life,” if I may say so. The goal was to convey the atmosphere of that era: the work of the Angkor Conservation, the people working at the temples, and the shift from the rainy season to the dry season. There is a bit of nostalgia in that book. It somehow idealizes that era. To be honest, I have dreamt of living at that time and work on the renovation of the temples. Thanks to the book, I gave myself that gift.

François Camps: Even though the book truly is fiction, historic facts or real explanations of the ongoing archeologic digs feature throughout the story. Was it an important aspect of the writing to bring actual facts to the reader, in addition to the fictional story?

Alain Forest: First of all, I wanted to transmit the feeling of that special era of French colonization, where French and Cambodians got along pretty well, especially when working on the restoration of the Angkorian temples. It was pretty much the case until the mid-1930s or early 1940s. I think I did it right because some people actually think the book is about true events. It is always an achievement for novelists when they manage to make fiction seem more real than reality. But once again, the book is not a history book: I made connections between facts and events, but the dates do not match reality and the characters are totally fictional.

Nevertheless, I wanted to spread some knowledge through reading. For instance, when I talk about archeological digs, I use sufficient material and use the appropriate vocabulary to make people understand that I know what I’m talking about. But at the same time, I don’t want to go into too much detail. For instance, in the book, I never precisely describe what is an anastylosis.

François Camps: An anastylosis?

Alain Forest: The Dutch invented that technique in Java, Indonesia. Instead of trying to rebuild a temple, they started to reconstitute it using the materials they could find in the whereabouts, as stones never fall far from the original place. The idea was not to exactly rebuild a temple as it looked in the first place, but to preserve it as much as possible. If a stone was missing, they would use a similar one to replace it. But that new stone was not necessarily located exactly there in the first place.

The French were not proceeding this way at the very beginning of the conservation works at Angkor. It was all more archaic. But one day, some Dutch archeologists came to Angkor and made fun of them, telling them that they could do better work. After some months of training, the French ended up doing anastylosis too.

François Camps: You are a well-known researcher on Southeast Asian Buddhism, French Indochina, and are a professor emeritus at Paris Diderot University. After numerous research books talking about the region, why write a first novel?

Alain Forest: Exactly because of my research works! I spent my professional life digging for hours and hours into the archives of the French colonization in Indochina. They were not even classified when I started. So, writing a research book and a novel are two completely different things. Also, I’m retired now. I had told myself that I would write a novel once I would retire, so it was the right time.

François Camps: The book is also a good opportunity to talk about the Khmer traditional beliefs. As soon as they read the book’s headline, readers know that karma will play an important role in the plot. Is the book a meeting between two worlds: The Western one, very rational, and the Khmer one, where spirits and ghosts shape the world as much as the living?

Alain Forest: Daniel, the main character, is not really interested in it. But his suicide is not only based on rational behaviors. And Cambodians do have their own explanation for it. In the book, the Khmer governor of Siem Reap actually believes that Daniel is his son from an old life, as he has faith in the “Pouk Mdai Dae” belief. In a nutshell, this implies that after reincarnation, one would normally live another life surrounded by their relatives. But the chain can be broken if a major mistake is made and one will not be reincarnated with their former family. The governor actually believes that Daniel used to be his son, but he already committed suicide in a former life, causing him to be separated from his real original parents.

In the book, Cambodian beliefs slowly override Western beliefs. The conservation works at Angkor are disturbing the spirits of the temples. For Cambodians, Daniel is crossing dangerous lines that confuse and irritate the spirits. He was playing with fire … and eventually dies alone.

François Camps: You are now retired but you don’t seem the kind of person who actually stops working. Do you have any projects for the future?

Alain Forest: Not a novel. But I would like to write another research book to trace Cambodian history, from its origins to the present day.