Lantern and Rice Flake Festival: An Old Celebration for Youth?

- By Ky Soklim

- November 27, 2023 9:00 AM

SIEM REAP - Following the previous interview with Professor Ang Choulean, a renowned ethnologist of the Royal University of Fine Arts, senior journalist Ky Soklim aims to understand more about the meaning of the lantern and rice flake festival as they have something to do with youth and the Water Festival.

_1701009058.png)

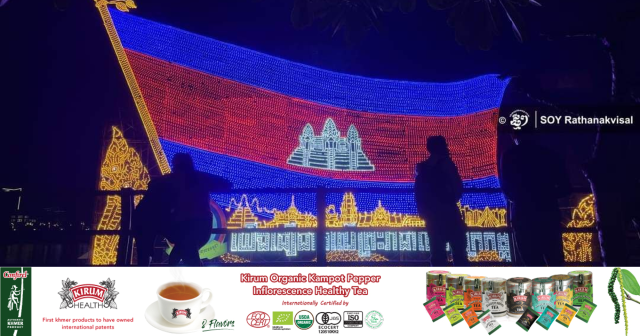

After being postponed for a number of years due to the pandemic, the government has decided that the Water Festival will be celebrated again from November 26 to 28. The main celebration will be in Phnom Penh while smaller celebrations will be held in some provinces.

To watch the first part of the interview, click here.

Ky Soklim: Does the Lantern Festival have something to do with the Water Festival?

Ang Choulean: Yes, it does. At the four-faced river in front of the royal palace in Phnom Penh, a large boat with a huge lighting system creates a beautiful light show at night. It has been somewhat like this for quite some time. In the local area, people generally use smaller water lanterns. In a way, the practice is to push out the bad luck by letting it flow downstream. However, the light itself also attracts human eyes. In Phnom Penh, fireworks also light up the night sky during this festival.

_1701008962.jpg)

Ky Soklim: How about “ok ambok” or the “shove eating of rice flakes”?

Ang Choulean: Ok ambok and sampeah preah khae are two names which can be used interchangeably depending on where you are. Sometimes, it is also known as “ok preah khae” or to “shove eating the moon”. Yet, this practice, as I notice in Siem Reap as well as the Thai province of Surin (A lot of Khmer descendants still live in Surin), have gone since the last two or three decades.

I also used to observe in other places such as the rural areas of Kampong Thom province, Kampong Cham province and most importantly Siem Reap province. From one province to another, the way it is practised is the same, but the way it gives out meaning is different.

In some places, monks, instead of spraying holy water while chanting, actually use rice flakes instead of water droplets. Rice flakes represent something whole, something complete. Plus, they also do it during the full moon.

At the same time, people also practise another tradition that involves candles to predict the future. Normally, they would get a certain number of candles on a spinning platform with banana leaves underneath.

When the candles are burnt, they create wax which flows down on to the leaves. However, the amount of wax is not the same between each candle. Therefore, they could predict the amount of rain in different parts in the following year.

What surprises me is another practice in some pagodas of Siem Reap province. It is still extensive. The practice is done only at midnight when the moon is full.

Teenage boys and teenage girls stand in two rows. The senior men of the pagoda will guide the teenagers to take turn and shove the rice flakes into each other’s mouth. As I heard, the senior man told the teenagers to keep looking at the full moon when he or she is given the rice flakes. Then, I realise the name “ok preah khae” or “eat the moon”. As it is done during the full moon, it coincides with the fact that teenagers are also full of energy. They are in their prime.

At the same time, the lunar month of Assu (mid-September to mid-October) was at the beginning of the year, not at the end of the year as we know it today.

Rice flakes are also new. They are consumed before they are processed and stored inside the granary. Research was conducted in 1968 by a French ethnologist named Jacqueline Matras into this kind of practice done by the Bru minority in Cambodia. Upon further research, I cannot find any of these practices being conducted in our neighbouring countries or even India. In general, it is a celebration for youth.

Ky Soklim: Why did seniors allocate this time for young people?

Ang Choulean: In the past, romantic love was strict for teenagers. It was not like today. It is hard for kids today to understand with all of these advances in social media. However, once in a while, this celebration allows kids to have some freedom. Similar to Khmer New Year, they may come together, play traditional games and have fun. Perhaps, they could even look at each other and inform their parents about who they like or love.

Conducted in Khmer for ThmeyThmey News, the interview was translated by Ky Chamna for Cambodianess News.