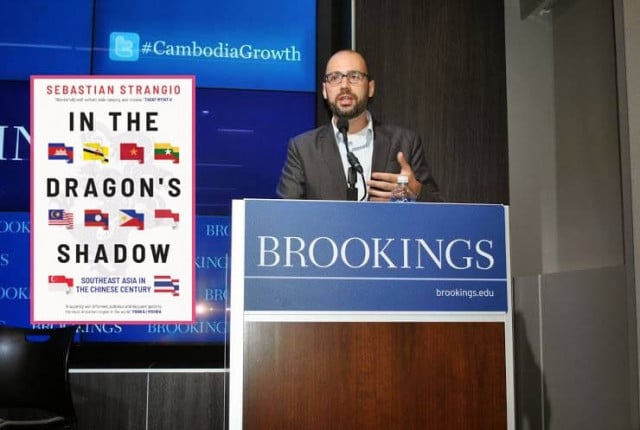

Sebastian Strangio on Cambodia’s Relations with China and the US

- Sao Phal Niseiy

- January 12, 2021 10:16 AM

Chinese influence in Cambodia is prevalent, and the ongoing great power rivalry has put the country in a more dangerous position, which requires Cambodia’s leadership to ensure a balance in relations with both China and the US. Cambodianess’s Sao Phal Niseiy spoke to Sebastian Strangio, author of the book: In the Dragon's Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese Century to discuss aspects of China’s rise as well as the implications of contemporary strategic competition between major powers for Cambodia.

Sao Phal Niseiy: In Chapter 4 of your book, you dig deep into the impact of rising Chinese influence in Cambodia. One of the most important points I want to raise is the question of Cambodians with ethnic Chinese descent. Do you think that they’ve had more influence in recent years, or if I can put it another way, have they driven closer relations between Phnom Penh and Beijing?

Sebastian Strangio: It is undoubtedly the case that warming relations between China and Cambodia have been paralleled by a thickening of economic, political, and cultural ties between ethnic Chinese Cambodians and mainland China. This has also occurred in other Southeast Asian nations, where China’s pivot from Cold War confrontation and subversion (Mao Zedong) to economic engagement (Deng Xiaoping) opened up economic opportunities for Overseas Chinese businesses, and reduced the stigma that attached to ethnic Chinese in many nations at the height of the Cold War.

Ethnic Chinese businesspeople were forced onto the back foot under the People’s Republic of Kampuchea during the 1980s, when Cambodia’s communist government persecuted them along similar lines to their patrons in Vietnam. But the anti-Chinese crackdowns in Cambodia were always slightly half-hearted compared to the situation in Vietnam, and it all ended when the Cold War did. In 1990, Chea Sim, the late president of the CPP [Cambodian People’s Party], told Cambodia’s Chinese community to “unite and liaise with your relatives and friends overseas, attract foreign investment and become a bridge to developing the economy.” Ethnic Chinese quickly reassumed their traditional prominent position in the Cambodian economy. They now form an important pillar in the economic edifice of CPP rule, and a useful “bridge” between the CPP government and expatriates and business people from mainland China.

Sao Phal Niseiy: Many people point to wealthy Cambodian Chinese people, who also hold high political positions within the country’s executive and legislative branches, appear to have been reaping the benefits from cumulative Chinese investments. What do you think?

Sebastian Strangio: It depends on the specific investments. But to the extent that many ethnic Chinese Cambodians have language abilities, cultural affinities, and political relationships that connect them to the People’s Republic, they have benefited disproportionately from the surge of Chinese investment to Cambodia. Of course, for many years, Cambodians of Chinese extraction have made up a significant proportion of Cambodia’s commercial elite—much as in other Southeast Asian countries—so this is hardly a new phenomenon.

The interesting thing about Cambodia is that ethnic Khmers have historically evinced little popular resentment toward Chinese immigrants Cambodians of Chinese extraction, unlike in other nations like Indonesia and Malaysia. Indeed, Khmer culture—and the porous form of Theravada Buddhism practiced in Cambodia—has been quite welcoming of ethnic Chinese, and they have assimilated deeply into Cambodian culture. I think this can be explained by the fact that Cambodia lacks a shared border with China, and that the bulk of Cambodian nationalist energy has been directed toward the more proximate threat: Vietnam.

Sao Phal Niseiy: With the change in US leadership, we expect to see democratization and human rights being scrutinized by Washington, and Phnom Penh will likely respond by leaning increasingly towards China. How do you see the future relations between the US and Cambodia, taking into account the Chinese factor?

Sebastian Strangio: My outlook for US-Cambodia relations is not overly optimistic. While I believe the two sides have a mutual interest in improving relations—for Washington, to pull Cambodia out of China’s orbit, and for Phnom Penh, to avoid to an unhealthy overdependence on Beijing—the mutual mistrust runs deep.

Since the early 1990s, American perceptions of Cambodia have been largely fixed: it is viewed as a nation with a tragic past whose chance at democracy was thwarted by Prime Minister Hun Sen and the CPP. At the same time the nation is seen as small and strategically unimportant, and is thus a place where the US can afford to stand up for human rights and democratic principles. This perception of the country has been reinforced by opposition leaders like Sam Rainsy, who are skillful at crafting their messages to Western constituencies.

For its own part, the CPP government has viewed American democracy promotion efforts as both hypocritical and threatening, as Rainsy and others have sought to encourage democracy promotion and harness it to their own ends. Indeed, this is one of the main things that has led Hun Sen’s government to embrace China with such alacrity.

In an era in which China’s rise has forced the US to make strategic accommodations with authoritarian and non-democratic governments across Southeast Asia in order to counter China’s influence, I predict that Cambodia will go the other way: its status as subject of democracy promotion efforts—as a place where Washington can afford to take a stand—will only become more important. This will only entrench the prevailing view on the Cambodian side, which is that the country has been held to unfair standards—and that the real American agenda is regime change.

For relations to improve, either Hun Sen will have to make substantial democratic reforms in order to assuage American concerns, or the US will have to adopt a more pragmatic approach toward Cambodia. Unfortunately, I don’t expect either to happen in the immediate term.

Sao Phal Niseiy: It appears that China’s influence will continue to grow in Cambodia in particular and Southeast Asia in general, and as long as it can offer enormous financial support to fuel the country’s growth and development, the Cambodian government will continue to embrace its closer ties with China. Do you agree with this statement?

Sebastian Strangio: China is definitely attractive to Hun Sen’s government, for the depth of its pockets and its “no-strings” method of engagement. But I wouldn’t take it too much at face value. Within the Cambodian government there are many who are uncomfortable with the country’s overreliance on China, and desire a greater balance in the country’s foreign relations. I also think that Hun Sen ultimately desires good relations with the US. The problem, as I alluded to above, is that his domestic political survival comes first—and that will always impose limits on how far relations with Washington can improve.

Sao Phal Niseiy: You also mentioned the precarious situation due to the Cambodia’s heavy dependency on China in the final part of Chapter 4. How dangerous it can be for small country like Cambodia amid the ongoing great power rivalry? How could the risks be minimized?

Sebastian Strangio: Again, Cambodia is in a very difficult situation, where both the hard power and ideological currents of US-China competition are present in concentrated form. Hun Sen has to make democratic reforms, give some slack, in order to improve relations with Washington; on the US side, as I’ve mentioned, there is a need to view Cambodia in a more realistic and less ideological light. There is certainly appetite for improved relations among certain segments of the Cambodian and US governments, but without movement on these core issues, progress will be constrained. At present, I don’t see either side giving any ground.

Sao Phal Niseiy: Many countries in the region including Cambodia seek closer relations with China because of its refrain from interfering domestic affairs as well as its deep pockets. But taking into consideration the Chinese ideological and political dynamics, will China be able to genuinely build soft power—enough to challenge the longstanding global hegemons like the US in the near future?

Sebastian Strangio: China has always struggled to generate and project soft power. I think part of the reason is that the soft power is something that emerges organically from within the interstices of a society: it can’t be planned or formulated from the top down. Needless to say, this is something that the Chinese Communist Party struggles with.

The question is how much it matters for China, both generally and in the case of Southeast Asia. Soft power attraction may be an asset for a great power, but it will rarely convince a nation to do something that is against its perceived national interests. At most it serves a supplementary function; it softens the reality of hegemony. In the case of Southeast Asia, and Cambodia, China remains a geographic reality—one that the region, whatever its opinions of China, can’t afford to spurn or ignore.