The LEASTC Project: How Cambodia Moved against Child Sexual Abuse in the 2000s

- By Michelle Vachon

- January 22, 2024 10:30 AM

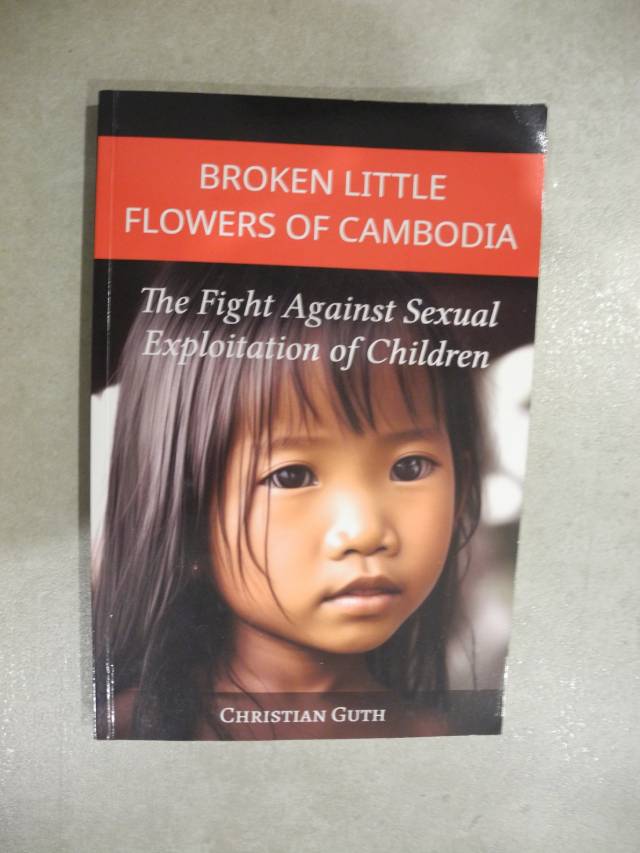

PHNOM PENH—The cover of the book features a lovely Cambodian girl more serious than a child of that age should be. And the title explains why. “Broken Little Flowers of Cambodia” tells the story of how the country took action in the 2000s to stop the sexual exploitation and abuse of children.

This is related by Christian Guth, a French police inspector who helped set up the special division tasked to handle these cases. Throughout the book, he explains situations and events that could only be described as tragic, but he does this and speaks of the measures taken to handle them in such a straight-forward and personal way that one wants to keep on reading.

When the Ministry of Interior and UNICEF joined hands to launch the LEASTC project (Law Enforcement against Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking of Children) in 2000, Guth had been in Cambodia for about six years. He had first run police training programs in the criminal investigation department, then been involved in setting up the Narcotics Bureau.

“My third mission was as unexpected as it was uncommon,” Guth writes. “I was to create a Heritage Police Unit.” In the 1990s, once landmines had been removed at the sites of pre-Angkorian and Angkorian monuments, thieves would come in and steal sculptures or even sections of monuments using sledgehammers and chisels, and then smuggle them out of the country for dealers who were selling on the international market. The Heritage Police would put an end to this, Guth writes. Today, Cambodia remains one of the rare countries along with Italy to have a heritage police.

That project done, Guth was not sure what he would do next, he writes. Having turned down an offer to lead a police training unit, he returned to France for a few weeks, then visited Myanmar, Laos and Malaysia but, he writes, “Cambodia was always my home port.”

This is when the perfect opportunity came up: serving as international police advisor to the LEASTC project. “Before the year 2000,” Guth writes, “the Cambodian police made no effort to protect minors from sexual exploitation.” With the Khmer Rouge still roaming the country, he explains, “the authorities’ number one task was ensuring the peace and safety of civilians.”

The launch of the new unit would help address a problem that, by then, was affecting the country’s reputation, Guth writes. “Cambodia was being described in the global media as a kind of Wild West where pedophiles from around the planet were swarming in.” Prum Sokha, then secretary of state at the Ministry of Interior and today senior minister, served as chairman of the LEASTC coordination committee, and his support proved essential, Guth said. The project involved training officers for the Anti-Human Trafficking Juvenile Police (AHTJP) and get to work.

Police officers discuss procedures regarding operations at a hotel in 2005. Photo: provided

Police officers discuss procedures regarding operations at a hotel in 2005. Photo: providedPolice officers of the LEASTC project operated on two fronts: sexual exploitation of children as a business in hotels or set locations, and sexual abuse of children at home, at school or in their daily lives because, as in about every country in the world, some boys and girls in Cambodia were abused by relatives or people of authority such as teachers. “The hotline was the first manifestation of our efforts and would be the first link in a chain that grew from thirty cases in 2000 to over 700 in 2005 alone,” Guth writes.

“There was work to do: About a third of the approximately 15,000 sex workers in Cambodia were children from 12 to 17 years old,” he writes. “It was necessary to act, to revolt against the trampling of these ‘little flowers.’ Street children and little girls from poor families, rotting in brothels that became their prisons.”

In the chapter entitled The Ogre of Sihanoukville, Guth speaks of an infamous case in which boys were kept imprisoned in a “recreation center.” Two of these boys had been found on the street by social workers of the NGO Mith Samlanh/Friends; they had their private parts bound in locks. The human rights NGOs LICADHO and One House, which had put the “recreation center” under surveillance, had seen men going in and leaving with boys.

The man behind this was Pierre Guideno, an elegant Frenchman in his 40s whose family had influence in France’s political circles. So, some people of the French Embassy and powerful businessmen attempted to have him released without being charged. “The Embassy did not get what it wanted,” Guth writes. However, his lawyers went to work, and the examining prosecutor dropped the charge of rape and only kept a charge of confinement even though six children had testified having been sexually abused by Guideno. Released on bail, the man was put on trial in Sihanoukville where photos and videos were submitted along with testimonies. And yet, he was only sentenced to six months in jail for having a gun, which was illegal. One of the NGOs filed a complaint against him in France, but Guideno died before appearing in court, Guth writes.

Even though the outcome was not what his police unit had hoped for, the case served a purpose. “Cambodia needed to correct its image of a country where crimes against children go unpunished, and the media coverage of this affair helped by warning off pedophile predators from around the world who saw this little nation as a chosen land,” Guth writes.

The LEASTC project measures included a hotline for people to report cases, flyers and also posters at airports warning that sexual aggression on children was a crime in Cambodia and that the police would act against those committing it, he said.

Police officers of the LEASTC project worked on all fronts, rescuing underage boys and girls from hotels in cities or prostitution houses in areas such as “Kilometer 11,” or K-11, in Svay Pak district north of Phnom Penh, dealing with human traffickers, and also handling individual cases of children raped by relatives, neighbors or people who deal with children such as teachers.

Although countless children are raped by relatives, he writes, “very few of these cases are reported to the police. Because incest, [in Cambodia] as elsewhere, in rich or poor families, is a crime that often gets buried…imposing the victim’s silence and very often that of the whole family.”

But one woman decided not to do this and, after consulting a lawyer whose work included the protection of children in Battambang city, she contacted the LEAST unit.

This woman had just been told by her two daughters that her husband had been raping them since childhood. The family had a small farm outside the city and, when his wife went to sell water chestnuts at the market, her husband would rape them. Coming home early one day, she surprised him in bed with their 15-year-old daughter. Upon hearing from her that this had been going on for years, and in spite of her husband’s apologies, she reported him to the LEAST unit even though this would mean not having him work on the farm to help support the family, and also having relatives and neighbors find out. The man was condemned to 18.5 years in jail during his trial.

Guth mentions a variety of cases the unit dealt with. One involved an oknha—a title that, since the 1990s, has involved the person making a financial contribution to the government that went from $100,000 to $500,000 in 2017. This oknha had “ordered” a virgin from a brothel owner. “Poan [the oknha] knew that in stealing their virginity, the girls he raped would have difficulty finding a husband and become a dead weight to their families, and to survive…But he couldn’t care less,” Guth writes. This oknha, was arrested as he was paying the brothel owner for a 14-year-old girl who was being held by one of his bodyguards.

On previous occasions, the oknha had come to an arrangement with the police officers nearby, as paying the authorities and police officers would be seen at the time in cases of child prostitution, pedophilia or other crimes.

This poster was displayed by the LEASTC project throughout the country to let people know where to call to report sexual abuse of minors. Photo: provided.

This poster was displayed by the LEASTC project throughout the country to let people know where to call to report sexual abuse of minors. Photo: provided.Cases the LEASTC unit handled included a woman who recruited 15-to-19 year-old girls in a village in Siem Reap province to work in a laundromat in Poipet, but who actually ran a massage parlor with prostitution where her husband and a guard kept the girls in line at gun point. Still, one girl managed to escape and return to her family that alerted the LEASTC unit, Guth writes.

His team was involved in cases of illegal adoptions of babies being taken overseas, of girls agreeing to go abroad to get married only to be forced into prostitution, of street children from the provinces—boys—who were thrown into prostitution by Madam X in Phnom Penh, and of miners taken into prostitution across border. The unit even identified a site on the internet offering foreigners a package tour to Cambodia that included teenage virgin girls. “The National Central Bureau of INTERPOL was brought in at that point and the investigation took on an international dimension,” Guth writes. “The case helped the Cambodian police move up a notch in the fight against pedophilia.”

The LEAST unit would often work with INTERPOL (the International Criminal Police Organization) and foreign police forces in cases across borders and/or cases involving foreigners, Guth writes. Especially since, while suspects are usually tried in the country in which they commit crimes, in the case of sexual crimes against minors, several countries repatriate their citizens. They are then tried under their county’s jurisdiction, he writes, “generally far less tender with pedocriminals abusing children in foreign countries.

“With the Americans, for example, the process unfolded quickly,” he writes since Cambodia had concluded an agreement with the United States. “[W]e knew the aggressors would pay dearly in the American judicial system, unless perhaps they had the means to hire a top-flight legal team.”

The LEASTC unit would be referred cases by NGOs dealing with people’s rights such as LICADHO and ADHOC, NGOs focused on women’s rights such as AFESIP and Cambodian Women’s Crisis Center in addition to those working with children including Krousar Thmei, Pour un Sourire d’Enfants (PSE), and Mith Samlanh/Friends. Some of them would pass on information to the LEASTC unit when they would come across children who had been violated, and others would take care of them after the unit had taken action since a police unit was not in a position to do this once their testimonies had been taken. Testimonies that police officers would get trained to take from children so that this would not add to the trauma they had suffered.

Some NGOs’ initiatives affected the unit’s work rather than help, Guth writes. For instance, the Christian NGO International Justice Mission helped organize and took part in a raid on K-11 with 60 police officers from Phnom Penh’s criminal investigation unit based on the information the NGO had supplied, he writes. This led to the arrest of 12 pimps and the rescue of about 30 underage prostitutes with the event getting extensive media coverage.

However, Guth writes, this operation was in fact counterproductive. Prior to the raid, prostitution was concentrated in Svay Pak, which made it easier to control, he writes. The raid made it spread out, he writes, “which was bad for the police and for the women who worked there under duress.” An NGO should not intervene as a second police force, he stressed.

There was also an NGO that helped the police make two arrests in the same hotel two weeks apart. While going over the reports, Guth realized that the victim was the same 14-year-old girl in both cases. The NGO denied having used her as bait, which amounted to endangering a child to trap a criminal. But this did not convince Guth who viewed this as the NGO needing to show results to raise funds and get media coverage.

One extreme case of this involved the NGO AFESIP whose director Somaly Mam would later be accused of lying about virtually everything, from her own childhood during which she claimed to have been sold to a brothel by a man saying he was her grandfather, to the situation regarding child sexual exploitation in the country— https://www.newsweek.com/2014/05/30/somaly-mam-holy-saint-and-sinner-sex-trafficking-251642.html and https://southeastasiaglobe.com/somaly-mam/ .

Believing that child prostitution was taking place at a hotel in Phnom Penh’s Tuol Kork district, AFESIP conducted a 2-month investigation assisted by LEASTC police officers. This having produced no proof that this was the case, the LEASTC unit declined to raid the hotel as Mam was asking.

But she managed to convince General Un Sokunthea who headed the LEASTC unit as well as National Police Commissioner General Hok Lundy to proceed. “The operation took place late one afternoon,” Guth writes. “About twenty police from the AHTJP [Anti-Human Trafficking Juvenile Police] rushed into the hotel accompanied by Mam and the other AFESIP leaders, a staff member from the prosecutor’s office and the French television crew.

“In the ensuing panic, about half the girls managed to run away but eighty-three were ‘rescued,’ including masseuses, the Ta Ta mistresses and some hotel staff,” Guth writes. “The intrepid television crew garnered some sensational images to illustrate a report on the NGO’s marvelous courageous combat against the sexual slavery of Cambodian children,” he writes. However, after identity verification, all the girls were over 18 years old—therefore not minors—except for one girl who was 17 but was not involved in sexual activities.

The young women were sent in the care of AFESIP that was not equipped to house them but managed to accommodate them for the night. But since the girls had been left their mobile phones, they called friends or family and rushed out of the center when they arrived to pick them up. “Mam announced to the media that armed men wearing military uniforms had descended on the center, broken down the gate and forcefully taken the girls after threatening the life of the director and all the personnel,” Guth writes. But witnesses and the officers who investigated the incident said the gate had been forced open from the inside and the girls had left willingly.

Sticking to her tale, Mam alerted the embassies, closed the center and left the country to, she said, take refuge in Bangkok. “The soap opera burst to life once more the following week, when hotel personnel and women designated as prostitutes filed complaints for defamation and false imprisonment,” Guth writes.

Western embassies then blamed the Cambodian authorities for irregularities when apprehending the people arrested and for enabling child prostitution. The whole episode tarnished Cambodia’s reputation and, Guth writes, “Cambodia’s genuine efforts to fight human trafficking…Only the NGO came up a winner in this game of deception.”

This episode also demonstrated that, he writes, “[O]nly by training police officers in the painstaking work of criminal investigation, with respect for procedure, could they garner real success.”

Christian Guth is photographed during a recent trip to Cambodia. Photo: provided

Christian Guth is photographed during a recent trip to Cambodia. Photo: providedIn his book, Guth also speaks of prostitution that, he writes, in addition to the fact that it must never involve minors, should not involve adults forced directly or indirectly into prostitution and, if it’s the case, should have those forcing them prosecuted.

But if adults get into this trade voluntarily, this is another matter, Guth writes. Some Cambodians who get into this trade to support themselves and/or their families will go to Bangkok or Poipet to do so not to have their relatives or friends know what they do for a living, he writes.

Since prostitution exists due to a demand that is not about to fade away, he writes, regulating it could ensure “just and favorable conditions of work” and protection for these workers. Among other things, this would free police officers and enable them to focus on criminals such as the organizations that get young girls into prostitution through rape and violence, Guth writes. In the case of those organizations, he writes, “let us be pitiless toward all those who profit from that abominable trade in human beings.”

The AHTJP project lasted 10 years. “This experience…sets social phenomena of a particular era and can serve as reference for other countries wishing to set up such department,” Guth said during an interview. At the time, poverty, the weakness of the judicial system, which led to a culture of impunity, was contributing to the sexual exploitation of children, he said.

« When we set up this unit, we realized right away that we had to do prevention,” he said. “So as early as 2004, we started setting up a prevention campaign in schools…especially for the 12-to-15 year-old students.”

These efforts continue today and now include warning minors against online pedophiles. Because among other traps online, he said during the interview, “there are pedophiles who take on the profile of a 14-year-old, become friends with a 13-year-old girl [or boy] and when they meet, he is 40.”

Cambodia, which is a member of the Global Alliance Against Child Sexual Abuse Online, launched in 2021 the National Action Plan to Prevent and Respond to Online Child Sexual Exploitation in Cambodia (2021–2025).

Christian Guth’s book on the LEAST Project in Cambodia. Photo: provided

Christian Guth’s book on the LEAST Project in Cambodia. Photo: providedThe years Guth spent in Cambodia took their toll on his private life, limited the time he could spend with his children, and led to a divorce with his wife, he said in interview and even mentions in his book. But he does not regret those years spent in Cambodia working on this project.

Whenever Guth would mention the work he was doing in Cambodia to people in Europe, they would say how horrible they had heard the situation was. He would then point out that sexual assault on children is a universal problem. “What is happening in this country is also happening in France, in Germany and everywhere else,” he said. “One must not think that this is an ill necessarily Cambodian or Asian: This takes place everywhere.”

Guth’s book was first released in French in 2022. The English-language version was released in 2023, translated and edited by Teia Laudouar. But rather than a straight translation, the English-language version of the book was done with the English-language readers in mind rather than a straight translation.

Guth spent 10 years on this project. Today, he said, “I’m as passionate about this work as I was at the time.” Combatting child sexual abuse, he writes at the end of his book, “(a)n incessant and uncompromising struggle it was, and still is, not just in Cambodia but around the world.

The book “Broken Little Flowers of Cambodia” is available in Phnom Penh at the bookstore Carnets d’Asie at the Institut Francais on Street 218. Tel.: 023-210-421 / 017-967-804

To request help or report a situation at the Child Helpline Cambodia, call 1280.The helpline can also be reached on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/chc1280/

People assigned to the helpline can take calls or answer via Facebook in Khmer and in English.