The Real-World Puzzles of the Bayon Temple’s Smiles

- By Sem Vanna

- April 15, 2024 12:00 PM

SIEM REAP — As restoration work progresses at the Bayon temple in the Angkor Archeological Park, stones that had fallen off the famed faces on its towers are being put back in place by teams of archeologists and specialized workers. This painstaking work requires a great deal of dedication, patience and hard work on the part of all involved.

_1712995910.png)

Caption: The towers of Bayon temple featuring the highly-recognisable four-faced deity. Photo: Chhorn Sophat

When the capital of the kingdom was moved south following the Siamese attack on Angkor in 1431, the monuments were left to the jungle, except for brief periods in the 16th and 17th centuries during which the court returned to the site. When, at the turn of the 20th century, archaeologists took on the restoration of the monuments following the signing of the French Protectorate, they were confronted by the damage caused by the jungle, which had taken over the site, and by natural forces such as rain and wind that had wreaked havoc on some of humanity’s most awe-inspiring monuments even though they had been built of heavy stones.

_1712996101.png)

Caption: Bayon, a temple situated at the center of a larger archaeological complex called Angkor Thom. Photo: Chhorn Sophat

Set at the center of the enclosed city of Angkor Thom, which is today about 10 kilometers from Siem Reap city, the Bayon, with its signature faces, has been steadily looked after and restored by restoration staff such as Mom Pum who spend most of their days crisscrossing archaeological sites, and looking for scattered stones and possible connections between them.

_1712996331.png)

Caption: Mom Pum, a restorer at the APSARA National Authority. Photo: Moeurn Makthong.

With a measuring tape in his hand, Mom Pum walks from one stone to the next, checking their dimensions, characteristics and location orientation as stones are usually laid in an orderly fashion around the temple.

“It is easier to connect stones when there are sculpted elements on their surface,” Pum said. “We just need to follow the pattern to find stones that go next to them.”

_1712996458.png)

However, not all stones have signature sculptures on the surface. Structural stones, often plain looking, demand from stone finders a special understanding of the characteristics of stones including protrusion or intrusion.

“I need to keep track of the measurements of each stone and use this data when checking other stones, whether they are a match or not,” Pum explained.

Just like many other temples in Angkor Park, the Bayon is a geometrically complex structure. It was built by King Jayavarman VII in the late 12th - early 13th century, and stood exactly in the middle of his capital city of Angor Thom. Although the actual numbers are still being debated, according to some sources, the temple exhibits 54 towers with 216 faces. And some faces differ from each other: they are not identical.

_1712996628.png)

“We are able to recover a number of stones,” Pum said. “However, if the old stones are too weak to be reused, we need to replace them with new stones. Some stones are presumed lost.”

Even after being in this field for 30 years, Mom Pum still experiences times of stress when he works. “To me, finding stones is harder than reassembling them,” he explained. “When it gets too stressful, I tend to take a break for a couple of hours just to clear the air.”

_1712996684.png)

Mom Pum has also worked on the restoration of the Baphuon temple and at the Western Mebon temple restoration site, massive restoration projects undertaken by the École française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO), or French School of Asian Studies, in Angkor Park during which finding scattered stone was a very daunting task, he said.

“To better locate each stone, I used to listen to stonemasons and sculptors,” Pum said. “By better understanding the sculptures, we can better connect the dots.”

_1712996822.png)

According to Kim Sothin, deputy director general of the APSARA National Authority—the Cambodian government organization managing Angkor Park—there still is a great deal of work to do at the Bayon. Where to put many stones that have fallen off the monument remains to be determined due to a lack of people such as Pum with this specific skill.

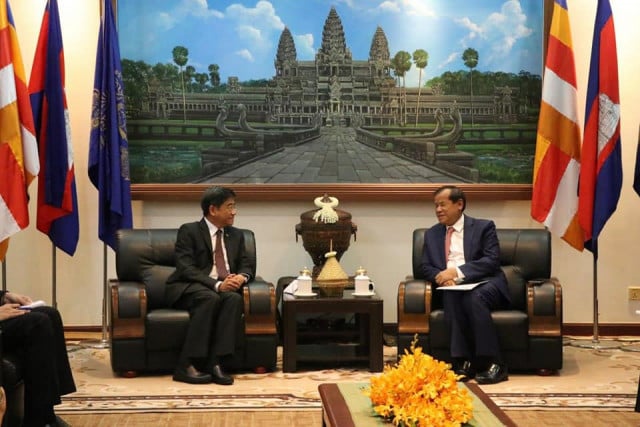

_1712996871.png)

Caption: Kim Sothin (centre), deputy director general of the APSARA National Authority. Photo: Moeurn Makthong

“Sometimes, we first pile up in one place a group of stones that supposedly go together,” he said. “Then, we test them to see whether or not they match with each other.”

Sometimes, what seemed to be straightforward turns out complicated, Sothin said. For example, he said, “[t]he lips on the face of Brahma at the lower level may be smaller than those of its counterpart at the upper level. This could be one way to spot the difference. Nevertheless, we cannot say for sure.”

_1712997010.png)

One way to identify where stones belong is by observing their characteristics along their edges, Sothin said. “Stones with a straight edge should be connected with another stone with a straight edge,” he said. “The same approach may apply to stones with non-straight edges or stones with rough edges.”

_1712997269.png)

Stone restorers are encouraged to learn French language as French restoration experts and archeologists with the EFEO kept meticulous records on stone placements and work conducted at temples going back to the early 1900s.

_1712997370.png)

The large copper statue of the four-faced Brahma set up at the new Siem Reap Angkor International Airport was inspired by the towers of the Bayon temple with their sculptures of faces. Click here to read about this huge statue.

Conducted in Khmer for ThmeyThmey Digital Media, the interview was translated by Ky Chamna for Cambodianess News.

To listen to the original interviews in Khmer, please click here and here.

Related articles:

Excavating the Bayon Temple’s Pond to Retrace its History

APSARA Authority to Restore the Bayon Temple’s Drainage System