The Urn Library: Remembering in a Peaceful Setting Those No Longer Here

- By Michelle Vachon

- December 28, 2023 2:10 PM

PHNOM PENH — The story of the Urn Library began several years ago when Youk Chhang entered monkhood for a time at Wat Langka in Phnom Penh at the suggestion of Venerable Sao Chanthol, the head monk of the pagoda.

Chhang’s sister had just passed away due to cancer, and he was having difficulty dealing with her death. So Chhang took Chanthol’s advice and, as men often do in Cambodia, became a monk for a time in 2015.

“[Chanthol] taught me to meditate, to relieve grief because he said grief reaction can last a very long time and it has to be you who do it yourself: Even the Buddha will not manage it for you,” he said during an interview on Dec. 18.

Chhang is executive director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-CAM) that researches and archives data on the crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge during their regime of 1975 through 1979, which caused the death of more than 2 million people. DC-CAM’s work extends to providing support to the survivors of the regime. Chhang was a teenager and in Cambodia during that regime.

When he arrived at Wat Langka, he started to explore the pagoda grounds.

“In the old hall, there was a big cement Buddha in a corner, in a small room packed with supplies,” he said. “I wondered why a statue of the Buddha was in a supply room, you know, like in storage…and it was big…When I came back around 4 o’clock in the morning, the sunlight came up right behind the statue. It was so dark, and then you would see the light [through] a whole right near the Buddha…coming from somewhere.

“Then I walked closer,” Chhang said. “The light was a very small point but, because it was so dark, I could see it clearly.” After discussing this with the monks, Chhang asked Chanthol’s authorization to move the statue to see what was behind it. “It took like 15 monks, really well-built monks, to move the statue,” he said.” And behind it, there was a path leading underground and at the end of it a door locked with a chain.

Suddenly, Chhang felt like the movie character Indiana Jones discovering treasures behind mysterious doors. “I was no longer a monk,” he recalled. “I thought wow, this is like Indiana Jones or [the actress] Angelina Jolie in [the movie] ‘Tomb Raider’…Then I asked the monks to break the lock and the chain. So, they did. When they opened the door, spiders, scorpions and snakes were running around. Then when we looked with flashlights, we could see all these urns that were buried, covered with ashes, not sand but ashes…piled up exactly like in a scene out of Hollywood.

“The room was huge,” Chhang recalled. “On the other side of the room, there was a Buddha standing and praying, and a Buddha sleeping. This raised the question whether they had built the cave on purpose to keep these urns.”

With Venerable Sao Chanthol’s authorization, Chhang said, “I told maybe 10 of my staff [at DC-CAM] and [photographer] Ouch Makara to remove the urns, clean them and photograph each of them…We spent about two weeks removing them one by one, cleaning and cataloguing them. Many of them had names and dates put on them, others did not. Some urns had messages attached to them, others had photographs.” One could see which urns contained the remains of the wealthy and which ones of the poor, he said. There were also remains simply wrapped in cloth.

“The story was confirmed for us when a couple of families…who asked to reclaim the urns told us,” Chhang said. In the early 1970s, as the Khmer Rouge were fighting against the Cambodian government forces and progressively making their way toward Phnom Penh, some people fled to the capital. As the situation deteriorated, some Cambodians brought the remains of relatives who had passed away to Wat Langka to have them safely kept, the future having become so uncertain. As the Khmer Rouge marched on Phnom Penh in April 1975, hundreds of these urns were hidden underground in this room behind the main hall. Then, a few urns were added in the 1980s, and there they all remained.

In the early 1990s, a handful of people returned to get the urns of their relatives. But most of these urns were left unclaimed, their relatives having died, immigrated during the 1980s or those still in the country being unaware that these urns were at the pagoda. In the meantime, the existence of the room eventually failed to be known at the pagoda as monks moved on or passed away.

This, until Chhang Chhang noticed a ray of light behind a statue of the Buddha.

With the agreement of Chanthol, Chhang wentabout setting up a special room at the pagoda to keep those remains. The room was designed by Sun Pora, an architect specializing in pagodas, Chhang said. A professor of architecture at the Royal University of Fine Arts (RUFA) in Phnom Penh, he has studied more than 200 pagodas built since the 1800s in the country.

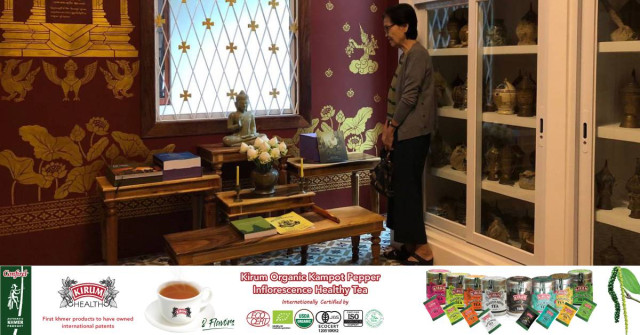

Located in one of the pagoda’s buildings, the room has been conceived as a place where people can spend a quiet moment. Which is why DC-CAM is calling it a library. “This is like a spiritual library,” Chhang said.

As Pora explained in early December, “[i]n addition to its functional aspects, the design of the library also places significant emphasis on safety, optimal air circulation, and ample natural lighting.

“Throughout the design process, our utmost priority was to create a space that serves as a respectful sacred site…while simultaneously creating an atmosphere that lessens any potential anxiety or fear among visitors,” he said.

Along two walls, wooden cabinets contain the urns that are placed on shelves behind glass doors. On the other two walls are golden artworks that are, Pora said, “commonly referred to as ‘boke’ style paintings, a renowned form of Khmer art that gained popularity during the early 1900s. They were commonly used as the decorative elements of pagodas across Cambodia during that period.”

Each boke is designed and then applied on the wall individually, he said.

“In the creation of a boke style painting, the initial step is to ensure a smooth and even wall surface,” Pora said. “Following this, an additional layer of paint is applied to create a smooth and seamless finish. Subsequently, the artists proceed to sketch the desired shape of the ‘kbach’ (ornament) or character on a sheet of paper. They then carefully cut out this shape, creating a template to be used as a mold.

“Next, the artists affix the mold onto the wall and delicately apply golden paint to the shape using a paintbrush, carefully following the outline provided by the mold,” he said. “Lastly, the artists carefully remove the mold from the wall, completing the process.”

As for the statue of the Buddha in the room, it is that of the Buddha, Pora said, “facing eastward, imparting the Thamajak Dharma, representing the foundational teachings, to a group of five Buddhist monks.” This being a library located in a pagoda.

While the library is now home to the 464 urns and containers found in the underground room, it was built to welcome up to 800 urns, Chhang said. This will make it possible to take care of urns that people can no longer keep at home—according to tradition, some Cambodians take home the funeral urns of their loved ones—or cannot afford to get a stupa to put them in at a pagoda, he said.

“I got a request [on Dec. 23] from a woman in Kampong Chhnang who wants to bring her father’s urn to place it here,” Chhang said. “She is poor and she feels that this room is heaven.”

One Vietnamese woman whose husband died in Cambodia in the 1980s has also decided to leave the urn with his remains in the library, he said. She had been coming every year to Cambodia in memory of his death. And now that the urn with his remains has been found, she wants the urn to be in Cambodia. As Chhang explained, “she believes that he belongs here.”

In the meantime, the monks at the pagoda are still in search of one urn: the one containing the remains of Preah Nhanapavaravichea Louis Em who oversaw the construction of Wat Langka and was the first head of the pagoda in 1912, Chhang said. The monks are wondering whether the urn of his remains is among the ones found in the underground room, he said.

The Urn Library is open to visitors 7 days a week from 8:00 am to 6:00 pm. People can enter the pagoda grounds through its main entrance on Sihanouk Boulevard near Independence Monument, or its entrance on Street 51, and then ask the way to the Urn Library.

For more information on the Urn Library, people can contact Seang Chenda at DC-CAM at 012-663-611.