Taking Care of Those Who Survived: Health Survey of People Who Lived during the Khmer Rouge Regime

- By Michelle Vachon

- October 4, 2023 10:50 AM

PHNOM PENH — Three decades have gone by since parliamentarians at the National Assembly adopted the country’s Constitution, which put an end to conflicts in Cambodia and enabled people to start recovering from the Khmer Rouge regime and the years of war. It is in a country at peace that people will start celebrating Pchum Ben on Oct. 13 and remembering those who are no longer here.

In 2023, around two-thirds of the population is believed to have internet access, and many have the understanding, if not the tools or resources, to truly be part of today and tomorrow’s Cambodia.

Still, among the people who quietly returned to their cities and villages during the 1980s or early 1990s, many have had difficulty dealing with physical conditions developed during those dark years, let alone the old fears and occasional nightmare they never talk about.

This led the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) to launch in 2019 a project that consisted of reaching out to some of these people in the countryside to find out about their health and whether they were getting the care and medicine they needed. The project, which was funded through a grant from the U. S. Agency for International Development (USAID), also included taking those in need of immediate care to private medical clinics that were volunteering their services for this program.

The interviewers involved in the project were young Cambodians from these communities, explained Youk Chhang, executive director of DC-Cam.

The project that had started in 2017, ended up lasting longer than planned due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “We adapted to the situation,” Chhang said. “Our volunteers were already getting first-aid training to help survivors…They got trained on explaining measures such as wearing masks.”

Although the actual work for the project was delayed, these young Cambodians contacted a total of 31,000 people between August 2021 and August 2022, as mentioned in DC-Cam’s report on the project “Health and Welfare of the Survivors of the Khmer Rouge” released in late September 2023 — https://www.dccam.org .

“We trained them to ask only two questions,” Chhang said. “The first question…was ‘what do you remember the most.’ And the second question ‘how are you today, how is your health today.’” Of course, the students asked more than two questions, but training them to focus on these two themes helped them remain on course when they were interviewing people, he said. This also led students to read history books because they wanted to make sure they would understand what people would refer to when they met them, he said.

A student volunteer discusses with a man who survived the 1970s and 1980s, asking him about his health today. Photo: Documentation Center of Cambodia

A student volunteer discusses with a man who survived the 1970s and 1980s, asking him about his health today. Photo: Documentation Center of Cambodia

A total of 1,300 young people took part in the project. Seventeen to 24 years old, they had graduated from high school and were studying for undergraduate and in some cases graduate degrees.

They were interviewed as well as trained online, Chhang said. In fact, he said, the whole project was run by phone and computer aps and programs, which made it possible to operate during the COVID-19 pandemic as participants were already used to communicating that way.

The project consisted of students visiting in their communities people who had lived through the Khmer Rouge regime, survived and, in many cases, had more or less faded away once they had reached home—more than 2 million people died during the April 1975/Jan. 1979 Khmer Rouge regime.

Often on their own and in poor physical condition, they were rather surprised to see anyone, and especially young people, visit them and be interested in their wellbeing and their story.

A great deal of care was paid to the way the students would meet the people they were to interview and what they would ask them. For example, they did not try to find out what positions people occupied during the Khmer Rouge regime, that is, whether they were Khmer Rouge or workers during the regime although some people interviewed told them. “We don’t judge…We survived the Khmer Rouge,” said Chhang who was a teenager during the regime. “DC-Cam hardly uses the word victim. We are not in a position to judge.”

During their meetings, the young interviewers asked people about their health and how they were handling their ailments: whether they were usually getting medicine, seeking treatment and from whom. Some of their conditions such as hypertension, gastrointestinal disorders and mental illness were no doubt caused, if not aggravated, by life during the Khmer Rouge regime, the report summary noted.

What interviewers found out was that people tended to get medicine rather than seeing a public or private healthcare provider or go to a clinic or hospital. Most of them had been vaccinated for COVID-19, which was free.

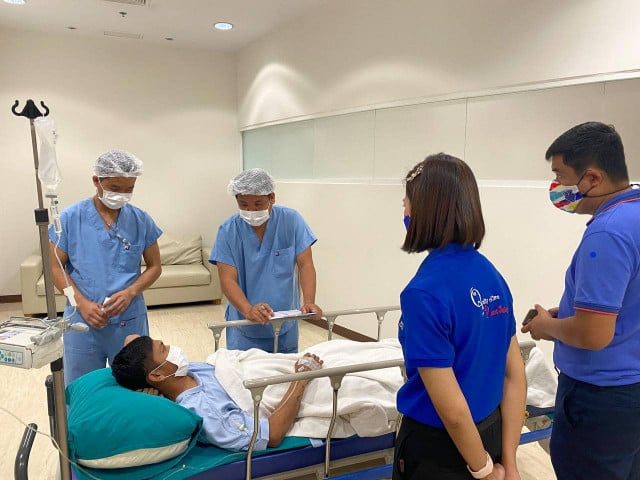

Since medical assistance had always been part of the DC-Cam project, those in need of care and willing to be helped were taken to the private healthcare providers who had volunteered their services for the project, Chhang said. “The program was to help survivors access social services and public health,” he said.

Still, the visits by these young people served a purpose beyond medical assistance because having a young person take the time to visit them and truly care about their health and situation was totally unexpected for most survivors.

“For them, it was ‘oh, you know us, you know me,’” Chhang said. “To them it was a great surprise, a wonderful surprise that someone still remembers them, that they have not been forgotten. And perhaps they feel [forgotten usually], you know, living in remote areas, being poor or isolated. I think you can’t deny that they have such feelings.

“And yet, you lived and you should not be haunted by those memories [of the Khmer Rouge time],” Chhang said. “And you still think of those who are no longer with you. But having someone come to your house and say hello, you know, 18 years old or 20 years old, and saying ‘I understand that you survived the Khmer Rouge. Can you tell me what you remember the most.’ I mean for them it was a tear of joy.

A team of two students at table and one man student at the back, etc., listen to a woman: A woman who lived through the Khmer Rouge regime discusses her health issues with a student. Photo: Documentation Center of Cambodia

A team of two students at table and one man student at the back, etc., listen to a woman: A woman who lived through the Khmer Rouge regime discusses her health issues with a student. Photo: Documentation Center of Cambodia

“I think that we got this from all the students,” Chhang said. “We got this from all over the place. Some of them said, ‘You’re asking me immediately, I’m not prepared to tell you the whole history. Let me think for a while so that I can tell you the whole history.’…Then we meet people in their kitchen, in the fields, sometimes at the market. People say, ‘you know, this is a long story. You should ask me more than one question.’ So, I think many people were prepared, wanted to tell their story for a long, long time but nobody had dared to ask.” Chhang also believed that some people were afraid they would not be able to tell their story before they died.

Among people interviewed, 63 percent of the men and 53 percent of the women reported their occupation as a farmer. The next higher category of occupations was unemployed or unable to work.

Regarding programs that could benefit them, “[H]ealth education would be the most impactful and least costly means for directly improving health and welfare of survivors, and such health education can be complemented by further research that explores the effects of the Khmer Rouge period on the particular illnesses, diseases, and ailments of survivors,” the report suggests.

There also are the other scars, as the report points out. Research conducted among people who suffered genocides across the world have shown that people who lived through such times carry lifelong scars that their descendants inherit. “DC-Cam looks forward to supporting initiatives that research or aim to improve mental health of the survivors and their families,” the report’s executive summary read.

In terms of reaching large communities of people who survived the regime, “[f]uture direct action or research programmes targeting survivor communities can target the Tonle Sap Lake and Plains regions of Cambodia; although, other areas of Cambodia, such as the Anlong Veng region, present possibilities for further research,” DC-Cam mentioned in its report executive summary.

Also in the summary, DC-Cam pointed out Prime Minister Hun Manet’s Pentagonal Strategy, its first part being human capital development whose focus includes health. “DC-Cam sees the Pentagonal Strategy as a prudent and extremely important step forward in balancing Cambodia’s rapid development with an equally important prioritization of the people at the grassroots level, who are the heart and soul of Cambodia,” the summary read.

In addition to helping people who survived the Khmer Rouge regime, looking into the social-and-health challenges they face today would also provide the world community with additional information on the after-effects of genocides, and show what people who have gone through such crimes and conflicts may need, DC-Cam wrote.

In the meantime, Cambodia needs to keep on recording people’s stories for its future generations. “Many survivors will pass away in the next five to ten years as many reach 70 years old or older,” DC-Cam summary read. “[U]nless we continue to dedicate resources and attention to collecting the oral history of this generation of survivors, we risk losing pieces of this history forever.”